| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 17, Number 1, January 2025, pages 35-43

Organ Damage and Its Associated Factors in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study

Lujain K. Alharbia, e, Ibrahim A. Al-Homoodb, Ammar A. Binammarc, Nojoud M. AlMuharebd

aDepartment of Rheumatology, King Salman Medical City, Madinah, Saudi Arabia

bDepartment of Rheumatology, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

cInternal Medicine Department, King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

dInternal Medicine Department, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia

eCorresponding Author: Lujain K. Alharbi, Department of Rheumatology, King Salman Medical City, Madinah, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted October 28, 2024, accepted December 11, 2024, published online December 31, 2024

Short title: Organ Damage in SLE Patients in KSA

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6129

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can affect a plethora of organ systems and cause organ damage due to the disease process and medication toxicity, notably corticosteroids. Patients with SLE often suffer irreversible organ damage. Older age, glucocorticoid use, longer disease duration, and disease activity all represent risk factors for organ damage. This study aims to assess the incidence and predictors of organ damage among Saudi Arabian SLE patients.

Methods: This study is a single-center, retrospective cohort observational study conducted at the adult Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic in King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. It included all patients aged 16 years and older who met at least four of the American College of Rheumatology Classification criteria for SLE or had a renal biopsy consistent with lupus nephritis and had regular follow-ups at our hospital, with the last visit occurring within 2 years.

Results: The study included 196 patients with SLE, predominantly female (92.9%) with a mean age of 36.2 years and an average disease duration of 8.88 years. Among the patients, 38.8% had a positive Systemic Damage Index (SDI) score. Hydroxychloroquine was used by 93.4% of the patients, and 46.9% had a Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) score of 3 or higher. The neuropsychiatric system was most affected, with 16.8% of patients having positive SDI scores in this domain, followed by the renal system at 9.2%. Patients with positive SDI scores were significantly older, had longer disease duration, and had higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension.

Conclusion: To address organ damage in SLE patients, integrating adjunctive therapies like antihypertensives and antidiabetic agents into management plans is essential. Future research should adopt prospective cohort designs to evaluate the dynamic interactions between comorbidities and organ damage over time. Additionally, studies should assess the effectiveness of combined treatment strategies and develop targeted approaches for high-risk groups to enhance outcomes and quality of life.

Keywords: SLE; Organ damage; Risk factors; Systemic Damage Index; SLEDAI-2K; Hydroxychloroquine; Corticosteroids

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) represents a classic autoimmune disorder characterized by a complex interplay of impaired clearance of apoptotic cells, increased activity of both the innate and adaptive immune systems, complement system activation, formation of immune complexes, and resultant tissue inflammation. These factors collectively drive a persistent autoimmune process. Since SLE can impact multiple organs and tissues, its clinical presentation and autoimmune features vary widely among patients and can evolve over time within the same individual. This condition affects individuals globally, with a notable predominance in women of childbearing age. Among SLE patients aged 15 to 44, the female-to-male ratio can be as high as 13:1, whereas in children and older adults, the ratio is closer to 2:1 [1].

SLE is a chronic autoimmune condition that alternates between active and remission states. It can affect a plethora of organ systems and cause organ damage due to the disease process and medication toxicity, notably corticosteroids. Organ damage has a significant impact on patients, including an increased risk of subsequent organ damage, higher mortality and morbidity, difficulties completing daily activities, and an increased economic burden on the healthcare system. Given its significant impact and the fact that SLE organ damage is permanent, it is critical to identify and decrease conditions contributing to its accrual [2].

Research indicated that organ damage affects about half of all patients with SLE within a decade of diagnosis despite disease control [3, 4]. The incidence of organ damage is particularly high during the first 2 years following diagnosis [5]. Patients with SLE suffer irreversible organ damage. Older age, glucocorticoid use, longer disease duration, and disease activity all represent risk factors for organ damage. Lupus nephritis (LN) has been linked with increased renal and overall damage [6].

Treat-to-target (T2T) strategies for SLE, developed by international task forces in 2014, are proactive management approaches that minimize organ damage by aggressively controlling disease activity with minimal use of corticosteroids. By using standardized tools like Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000 (SLEDAI-2K) to establish precise targets for remission or low disease activity, clinicians can rapidly intervene and prevent cumulative inflammatory damage to critical organ systems in SLE [7]. However, preventing chronic damage, particularly in the early stages of SLE, remains a significant challenge despite the implementation of T2T strategies [8].

The high incidence of chronic damage among SLE patients indicates that multiple factors may independently contribute to its development. In addition to disease activity, factors such as the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies and the use of certain medications, especially glucocorticoids, are closely linked to SLE-related damage [9, 10]. Recent research also highlights a potential genetic predisposition to specific types of organ damage, including renal and neurological issues [11]. Additionally, demographic factors like age, sex, disease duration, and comorbidities play a role [12]. This multifactorial nature of damage underscores the need for new outcome measures beyond assessing disease activity to also include evaluation of chronic damage [13].

The Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology (SLICC/ACR) Damage Index (SDI) was introduced in 1996 to assess the persistent impact of SLE on disease activity and to gauge irreversible damage resulting from both treatment and the disease itself [14]. The SDI evaluates permanent damage across 12 organ systems: skin, musculoskeletal, peripheral vascular, ocular, cardiovascular, neuropsychiatric, renal, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, endocrine including diabetes, gonadal, and malignancies. For most types of damage, it must be present for at least 6 months to be recorded, except for myocardial infarction and stroke, which are documented as soon as they occur. Over time, the SDI score reflects the cumulative accrual of damage, as it only increases with the occurrence of irreversible organ damage [14, 15]. The literature suggests that approximately 39-65% of SLE patients have damage to at least one organ (SDI ≥ 1), with values ranging from 0.6 to 2.3. Based on previous studies, the most common types of organ damage were ophthalmic, musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, and renal [16].

This study aims to address the significant challenge of organ damage in SLE, which varies by region due to genetic, environmental, and healthcare factors by assessing the incidence of organ damage and its associated risk factors. By focusing on the Saudi population, the research seeks to identify specific contributors to organ damage. Understanding these localized factors is crucial for developing targeted preventive and therapeutic strategies, improving patient management, and informing healthcare policies. This study will fill a critical gap in current knowledge and guide future research and clinical practices specific to Saudi Arabia.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This is a single-center, retrospective cohort observational study conducted at the adult Rheumatology Outpatients Clinic in King Fahad Medical City (KFMC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia between May 2022 and February 2023. KFMC is a leading tertiary care center with a capacity of 1,200 beds. KFMC serves as a referral hub for specialized care across the Riyadh region, managing over 30,000 inpatients and 500,000 outpatients annually. KFMC offers multidisciplinary care for SLE where patients are co-managed by rheumatologists and relevant subspecialists, such as nephrologists or neurologists, depending on organ involvement.

The study included all patients aged 16 years and older who met at least four of the American College of Rheumatology Classification criteria for SLE or had a renal biopsy consistent with LN and had regular follow-ups every 3 - 6 months at our hospital, with the last visit occurring within 2 years. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of King Fahad Medical City (FWA00018774, IRB00010471, and H-01-R-012).

Patients were selected from the EPIC system database of SLE patients at our hospital. Newly diagnosed patients who had less than 6 months of follow-up and those with incomplete laboratory or clinical data were excluded. Incomplete data were defined as the absence of key laboratory parameters (mentioned later) or missing clinical documentation required for calculating SLEDAI-2K or SDI scores. A total of 17 patients were excluded: seven due to less than 6 months of follow-up and 10 due to incomplete laboratory or clinical data.

Data collected included age, sex, age at diagnosis, organ involvement, and medication history including corticosteroids, hydroxychloroquine, mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and belimumab. Organ manifestations were classified based on the SDI. For example, renal damage was identified through persistent proteinuria (≥ 3.5 g in 24-h urine protein) or reduced glomerular filtration rate (< 50%) lasting more than 6 months, while neuropsychiatric damage included stroke or seizures persisting for at least 6 months. Laboratory findings included complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), renal profile, and urine protein. Results of anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA) testing by indirect immunofluorescence, C3 and C4 levels, and antiphospholipid antibodies (lupus anticoagulant as well as IgG and IgM isotypes of anti-cardiolipin and beta2 glycoprotein antibody) were also collected. Additionally, weight, body mass index (BMI), and bone mineral density, assessed through dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scans, were recorded. This information was gathered by reviewing electronic patient files and through phone calls with the patients.

The SDI was used to document the damage index (DI) for each patient, with a score of 0 indicating no damage and a score of 1 or more indicating damage. Additionally, the SLEDAI-2K from the last documented visit was recorded, with a score of 3 or more indicating active disease [17].

Statistical analysis

Data were encoded in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2018) and exported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 (IBM-SPSS Inc., Armonk, New York, USA) for statistical analysis. All continuous variables were tested for normality of distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk Test. Results were reported as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and as mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Significant differences in them were tested using the independent samples t-test. The association was performed using the Chi-square test and z test. Binary logistic regression was applied to assess predictors of organ damage. A P value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

The study encompassed 196 SLE patients, among which majority (92.9%) were females and 14 (7.1%) were males. The average age of participants was 36.2 ± 11.3 years, with a mean age at diagnosis of 27.3 ± 10.8 years. The average disease duration was 8.95 ± 5.6 years, ranging from 1 to 26 years. A total of 76 patients (38.8%) had a positive SDI score, while 120 patients (61.2%) had a negative SDI score. The majority of patients were treated with hydroxychloroquine (n = 183, 93.4%). Additionally, 92 patients (46.9%) had a SLEDAI-2K score of 3 or higher (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical and Demographic Profile of the Studied SLE Patients (n = 196) |

The majority of the patients had normal white blood cell (WBC) counts (n = 128, 65.3%) and platelet counts (n = 169, 86.2%). However, 97 patients (49.5%) had low hemoglobin levels. Over half of the patients (57.7%) tested positive for anti-dsDNA antibodies, while 59.7% had normal C3 levels, 85.7% had normal C4 complement levels, 81.1% had negative antiphospholipid antibodies, and 55.1% had normal ESR levels. Additionally, the majority had normal CRP levels (70.9%) and normal DEXA scans (91.8%) (Table 2).

Click to view | Table 2. Laboratory and Radiological Findings of the Studied SLE Patients (n = 196) |

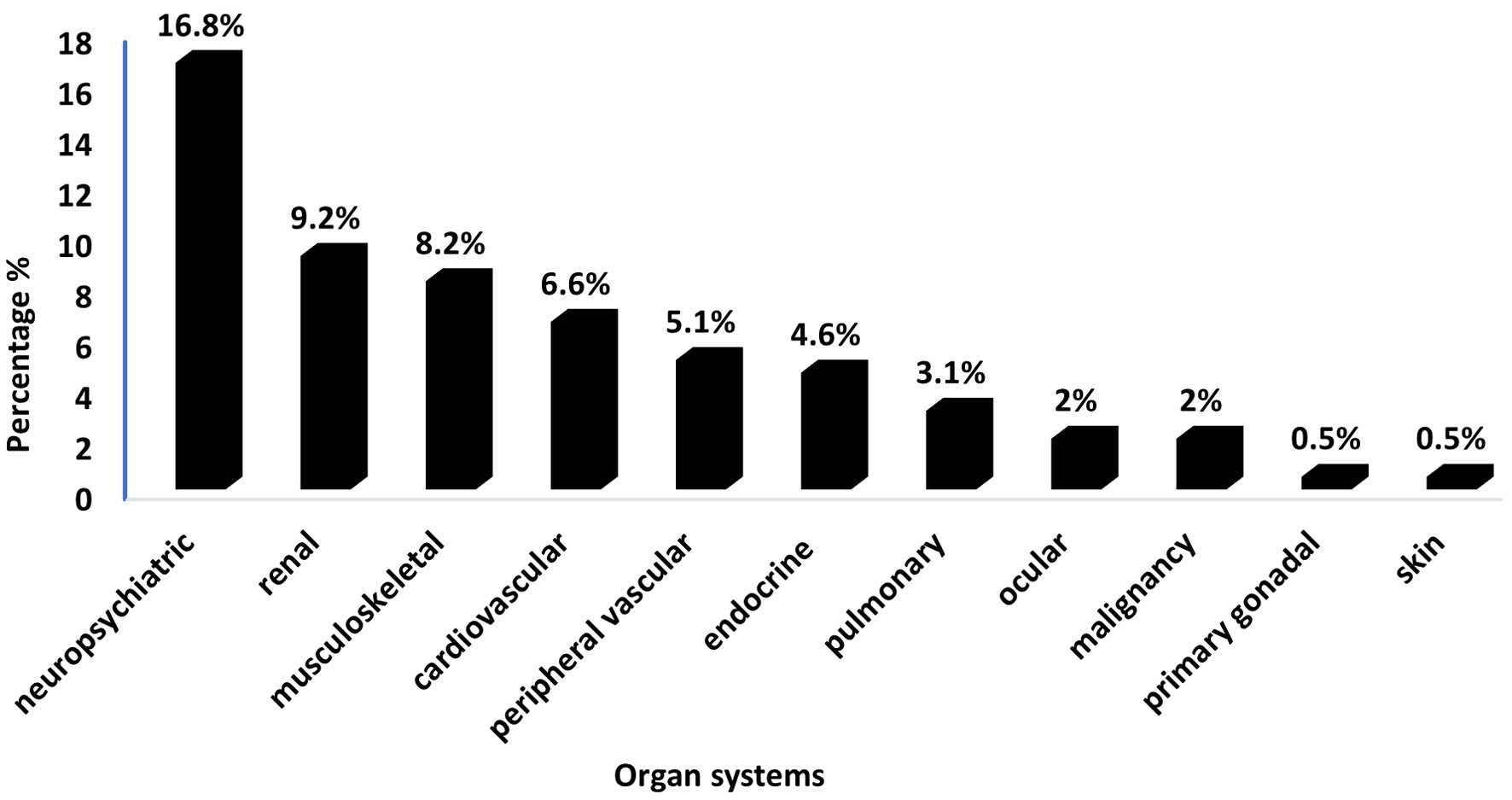

The mean age of patients with positive SDI scores was notably higher (38.93 ± 10.7) than those with negative SDI scores (34.45 ± 11.4) (P = 0.007). No significant distinction existed in the age at diagnosis between patients with positive and negative SDI scores (P = 0.154). Patients with a positive SDI exhibited a significantly longer disease duration (10.29 ± 5.59) in comparison to those with a negative SDI (8.11 ± 5.4) (P = 0.002). Diabetes was significantly more prevalent in patients with positive SDI scores (14.5%), as it directly contributes to the SDI score (P < 0.001). The small proportion of diabetes cases in patients with negative SDI scores (1.7%) likely represents pre-existing diabetes diagnosed before the development of SLE or independent of SLE-related mechanisms. Hypertension was also significantly more common in patients with positive SDI scores (26.3%) than in those with negative SDI scores (10%). The presence of positive anti-dsDNA was significantly linked with a higher proportion of negative SDI (56.6%) (P = 0.001). Conversely, variables such as gender, BMI, specific medications, WBC count, platelet count, hemoglobin, C3 complement, C4 complement, antiphospholipid antibody, and ESR did not display significant differences between positive and negative SDI groups, suggesting that they might not strongly influence SDI groups (Table 3). The neuropsychiatric system was the most frequently affected organ system, with 33 patients (16.8%) exhibiting positive SDI scores, followed by the renal system, which had 18 patients (9.2%) with positive SDI scores (Fig. 1). Neuropsychiatric manifestations included seizures requiring therapy for more than 6 months (n = 18), stroke (n = 13), transverse myelitis (n = 1), and chronic headache due to cerebritis (n = 1) (data not shown).

Click to view | Table 3. Comparison of Different Variables According to SDI Scores in the Studied SLE Patients (n = 196) |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Distribution of involved organ systems in SLE patients with positive SDI scores (n = 76). SDI: Systemic Damage Index; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus. |

Table 4 demonstrates results of multivariate binary logistic regression that was performed to identify independent predictors of organ damage, including significant variables from prior univariate analysis (Table 3). Diabetes emerged as a significant independent predictor, associated with a higher risk of organ damage (odds ratio (OR): 5.30, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.16 - 37.9, P = 0.049). Positive anti-dsDNA antibodies remained a significant protective factor, associated with a reduced risk of organ damage (OR: 0.39, 95% CI: 0.20 - 0.73, P = 0.004). Duration of disease (OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.00 - 1.12, P = 0.074) and hypertension (OR: 2.29, 95% CI: 0.93 - 5.66, P = 0.070) approached but did not reach statistical significance. Age was no longer a significant predictor in the multivariate model (OR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.98 - 1.04, P = 0.680). These results emphasize diabetes and anti-dsDNA antibody status as key independent predictors of organ damage, while suggesting potential contributory roles for disease duration and hypertension.

Click to view | Table 4. Multivariate Binary Logistic Regression to Predict Organ Damage (Positive SDI) in the Studied SLE Patients (n = 196) |

Patients with positive SDI scores were significantly older and had a longer disease duration (P = 0.007 and P = 0.005, respectively). They also had a notably higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (P < 0.001) and hypertension (P = 0.003). When examining SDI organ damage in relation to clinical features, males were significantly more prevalent among those with neuropsychiatric and renal involvement (P = 0.018 and P < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, patients with endocrine system involvement were also significantly older (P < 0.001) and were diagnosed at an older age (P < 0.001). There were no significant differences in BMI across the various organ systems. The use of corticosteroids was significantly higher in patients with musculoskeletal and renal involvement (P = 0.034 and P < 0.001, respectively). Additionally, anti-dsDNA antibodies were significantly less likely to be positive in patients with neuropsychiatric system involvement (P = 0.026) (Supplementary Material 1, jocmr.elmerjournals.com).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study assessed the burden of organ damage and evaluated the predictors contributing to it. Results highlight that the incidence of organ damage among our study population was noted to be 38.8%. While analyzing the data globally, a study from the United States revealed that within 5 years of diagnosis, approximately 33-50% of SLE patients experienced organ damage [18], while a German study indicated that organ damage prevalence increased from 60.5% at baseline to 83.0% after 6 years in all SLE patients, whereas 17.0% did not acquire organ damage [19]. Additionally, an Italian study showed that after a mean disease duration of 16 years and a mean follow-up of 12.9 years, 354 patients (69.3%) had sustained some damage: 49.7% had mild/moderate damage, while 19.5% suffered severe damage. Damage was present in 40% of 511 individuals 1 year following diagnosis, and its incidence rose linearly over time [20]. Moreover, a study conducted in Sweden concluded that over 40% of individuals experienced damage within 5 years, indicating that organ damage is a persistent concern [21]. The prevalence rate found in our study is marginally lower compared to some of these reported research studies, while one study reported a higher incidence than ours. This discrepancy could be due to various factors, such as differences in sample size, characteristics of the study populations, and other intrinsic factors specific to each study. We were unable to compare our findings with regional studies due to the scarcity of existing literature in this domain. Although there are studies addressing prevalence and predictors of mortality and survival, there is a notable lack of research specifically focusing on the incidence of organ damage in this vulnerable cohort. This gap underscores the significance of our study and emphasizes the value of publishing our findings.

Furthermore, the findings of the current study indicate that the organs most commonly affected were the neuropsychiatric, renal, and musculoskeletal systems, with damage rates of 16.8%, 9.2%, and 8.2%, respectively. Similarly, Ghazali et al reported that the majority of the participants experienced neuropsychiatric damage (21/94; 22.3%), followed by cutaneous (12/94; 12.8%) and musculoskeletal (6/94; 6.4%) damage [22]. Additionally, a literature review from the Arabian Gulf concluded that LN was detected in 10-36% of available renal biopsies and it may be more severe among individuals from the Arabian Gulf region than in other demographics [23]. A study by Taraborelli et al showed that the most frequently affected organs were the ophthalmic, musculoskeletal, and neuropsychiatric systems, which increased linearly during follow-up [20]. Although in our study cutaneous and ophthalmic systems were not frequently affected, their incidence of damage in literature highlights the significant and diverse organ damage burden imposed by SLE.

In this study, older age and a longer disease duration were significantly linked to organ damage. Similarly, another single-center study by Zivkovic et al concluded that organ damage was significantly related with age (P = 0.002) and disease duration (P = 0.015) [24]. However, on the contrary, Ghazali et al [22] and Bonakdar et al [25] did not find a significant association between organ damage and either age or disease duration. This discrepancy may be due to differences in patient demographics: 28.36% of our patients had a disease duration exceeding 10 years, whereas Bonakdar et al reported only 5.8% with such a long disease duration. Additionally, 24.52% of our patients were over 40 years old, compared to Ghazali et al, who had a majority of patients younger than 40 with a mean disease duration of 5.3 years [22]. Regarding gender, we did not find a significant overall association with organ damage in SLE patients, which is consistent with Zhang et al’s findings [26]. However, we observed that being male was significantly associated with neuropsychiatric damage (P = 0.018) and renal damage (P < 0.001).

Findings regarding the link between hypertension and organ damage have been varied. In the present study, we observed a significant association between hypertension and organ damage, which aligns with the results from Ghazali et al, Petri et al, and Conti et al [22, 27, 28]. Conversely, other research has found no significant correlation between hypertension and organ damage [24, 25]. Additionally, our study also demonstrated a significant relationship between diabetes mellitus and organ damage (P < 0.001). This association might be attributed to the increased risk of type 2 diabetes in women with SLE compared to those without the condition, potentially exacerbated by medications used for treating SLE [27].

While many studies have explored the relationship between anti-dsDNA antibodies and organ damage in SLE patients, our study found that anti-dsDNA antibodies were significantly associated with reduced risk of organ damage. This protective effect could have resulted from early and intensive treatment with immunosuppressive and immunomodulator agents or unique immune profiles in these patients that reduce the pathogenicity of the antibodies and associated organ damage. In contrast, Petri et al reported a significant correlation between recent positive anti-dsDNA and damage accrual in SLE patients [28]. The observed discrepancy may be due to differences in study design, such as the reliance on a single documented anti-dsDNA measurement, compared to longitudinal assessments used in Petri et al’s study.

The present study also found no significant relationship between antiphospholipid antibodies and organ damage. This is consistent with univariate analysis results obtained by Conti et al [27]. Similarly, in a study conducted by Taraborelli to assess the contribution of antiphospholipid antibodies to damage accrual in SLE patients, they reported no significant association between these antibodies and increased SDI at 10 and 15 years follow-up periods [29].

In the current study, a significant association was identified between anemia and renal damage. This finding is consistent with the results reported by Bertoli et al [30]. Additionally, it is noteworthy that patients with neuropsychiatric complications did not have a significant history of LN (P = 0.026). Also in our study, we found no correlation between disease activity and organ damage. This result aligns with the findings of Salah et al [31] and Legge et al [32], but contrasts with two recent research studies which showed a significant relationship between disease activity, as measured by the SLEDAI-2K, and organ damage [27, 28]. The discrepancy might be due to the fact that these studies likely monitored disease activity more frequently, which could have enhanced their ability to detect disease flares.

One of the most extensively studied medications is corticosteroids. In our study, we found no association between corticosteroid use and the SDI, which is consistent with the findings of Legge et al [32]. In contrast, other research has demonstrated a strong link between corticosteroid use and organ damage [27, 28, 33]. Petri et al specifically associated corticosteroid use with types of damage such as osteoporotic fractures, avascular necrosis, cataracts, coronary artery disease, and stroke [28] which differed from the types of damage observed in our patient cohort. Moreover, no significant association was found between hydroxychloroquine use and organ damage. This aligns with many studies that have reported a protective effect of hydroxychloroquine against organ damage [22, 24, 28]. In addition, our study found no significant effect of belimumab on organ damage, whereas Urowitz et al reported less organ damage in patients receiving belimumab [2]. This difference might be due to the relatively small number of patients on belimumab in our study. Overall, the relationship between therapies and organ damage is complex, involving a balance between drug toxicity and the potential benefits of better disease control.

Study strengths and limitations

One of the primary strengths of this study is that it is the first of its kind in the region, to the best of our knowledge. This pioneering work provides essential data on the prevalence and patterns of organ damage in SLE patients within a specific geographic area, filling a significant gap in the local medical literature. Additionally, by focusing on a unique population, the study offers valuable insights that are tailored to the regional context, which may differ from other areas due to genetic, environmental, or healthcare system factors. Furthermore, the study findings can serve as a benchmark for future research and help in developing region-specific guidelines and interventions. This pioneering aspect underscores the study contribution to enhancing the understanding and management of SLE in the region.

Despite its notable strengths, one key limitation of the study is its design as a single-center retrospective analysis. This design confines the study to data collected from a specific institution, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader SLE patient populations. The retrospective nature of the study also means that it relies on existing medical records, which can introduce biases or inconsistencies in the data. Besides, the single-center approach may not capture variations in patient management and outcomes that could occur in different clinical settings or geographical locations. These factors could affect the external validity of the results and the applicability of the findings to other settings or diverse patient groups. However, this study remains valuable and significant since it provides critical insights into the relationship between organ damage and various associated factors in SLE patients, which can inform future research and clinical practice. The study findings contribute to the understanding of disease progression and complications in SLE, offering a foundation for developing targeted interventions and improving patient management. Moreover, publishing such studies helps to highlight potential areas for further investigation and encourages multi-center research to validate and expand upon these findings.

Future research should explore the impact of comorbidities like diabetes and hypertension on organ damage in SLE patients, evaluate the effectiveness of adjunctive therapies, and develop region-specific management guidelines. Longitudinal studies and comparative research across different populations could also provide insights into treatment responses and early indicators of organ damage.

Conclusion

Our study found evidence of organ damage in 38.8% of patients, as indicated by the SDI score, with no significant association between organ damage and disease activity. Neuropsychiatric followed by renal involvement was identified as the most prevalent form of organ damage. Notably, damage was significantly more common in older patients, those with longer disease durations, and individuals with comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Given the impact of these comorbidities on the development of organ damage, it is crucial to incorporate adjunctive therapies, such as antihypertensives and hypoglycemic agents, into the management plans for SLE patients. Moving forward, future research should focus on investigating the interplay between comorbidities and organ damage in SLE, exploring the efficacy of integrated treatment strategies, and developing targeted management approaches for these high-risk groups to improve outcomes and quality of life.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Correlation of systems involved with clinical features.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

IAA conceptualized and designed the study and supervised the research. AAB wrote the original draft of the manuscript, focusing on the results and discussion sections, while NMA wrote the introduction and methodology sections. LKA supervised the clinical data collection, reviewed the collected data, contributed to data analysis, reviewed and edited the final manuscript, and managed project administration. Additionally, LKA, NMA, and AAB equally contributed to the literature review and data collection process.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

BMI: body mass index; CBC: complete blood count; CRP: C-reactive protein; DEXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; KFMC: King Fahad Medical City; LN: lupus nephritis; SD: standard deviation; SDI: Systemic Damage Index; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI-2K: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index 2000; SLICC/ACR: Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; T2T: treat-to-target

| References | ▴Top |

- Fava A, Petri M. Systemic lupus erythematosus: Diagnosis and clinical management. J Autoimmun. 2019;96:1-13.

doi pubmed - Urowitz MB, Gladman DD, Ibanez D, Su J, Mursleen S, Sayani A, Ross Terres JA, et al. Effect of disease activity on organ damage progression in systemic lupus erythematosus: University of Toronto Lupus Clinic Cohort. J Rheumatol. 2021;48(1):67-73.

doi pubmed - Stojan G, Petri M. The risk benefit ratio of glucocorticoids in SLE: have things changed over the past 40 years? Curr Treatm Opt Rheumatol. 2017;3(3):164-172.

doi pubmed - Gatto M, Iaccarino L, Zen M, Doria A. When to use belimumab in SLE. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(8):737-740.

doi pubmed - Rua-Figueroa Fernandez de Larrinoa I, Lozano MJC, Fernandez-Cid CM, Cobo Ibanez T, Salman Monte TC, Freire Gonzalez M, Hidalgo Bermejo FJ, et al. Preventing organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: the impact of early biological treatment. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2022;22(7):821-829.

doi pubmed - Murimi-Worstell IB, Lin DH, Nab H, Kan HJ, Onasanya O, Tierce JC, Wang X, et al. Association between organ damage and mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(5):e031850.

doi pubmed - Nikolopoulos D, Lourenco MH, Depascale R, Triantafyllias K, Parodis I. Evolving concepts in treat-to-target strategies for systemic lupus erythematosus. Mediterr J Rheumatol. 2024;35(Suppl 2):328-341.

doi pubmed - Ramnarain A, Liam C, Milea D, Morand E, Kent J, Kandane-Rathnayake R. Predictors of organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus in the Asia Pacific Region: a systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2024;76(5):720-732.

doi pubmed - Bernardoff I, Picq A, Loiseau P, Foret T, Dufrost V, Moulinet T, Unlu O, et al. Antiphospholipid antibodies and the risk of autoimmune hemolytic anemia in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21(1):102913.

doi pubmed - Ugarte-Gil MF, Mak A, Leong J, Dharmadhikari B, Kow NY, Reategui-Sokolova C, Elera-Fitzcarrald C, et al. Impact of glucocorticoids on the incidence of lupus-related major organ damage: a systematic literature review and meta-regression analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8(1):e000590.

doi pubmed - Marion TN, Postlethwaite AE. Chance, genetics, and the heterogeneity of disease and pathogenesis in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Immunopathol. 2014;36(5):495-517.

doi pubmed - Maged LA, Soliman E, Rady HM. Disease damage in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: Disease activity, male gender and hypertension as potential predictors. The Egyptian Rheumatologist. 2023;45:121-126.

doi - Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Natalucci F, Picciariello L, Olivieri G, Cafaro G, Bartoloni E, et al. Organ damage in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus patients: A multifactorial phenomenon. Autoimmun Rev. 2023;22(8):103374.

doi pubmed - Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Goldsmith CH, Fortin P, Ginzler E, Gordon C, Hanly JG, et al. The reliability of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology Damage Index in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40(5):809-813.

doi pubmed - Gladman D, Ginzler E, Goldsmith C, Fortin P, Liang M, Urowitz M, Bacon P, et al. The development and initial validation of the Systemic Lupus International Collaborating Clinics/American College of Rheumatology damage index for systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39(3):363-369.

doi pubmed - Sutton EJ, Davidson JE, Bruce IN. The systemic lupus international collaborating clinics (SLICC) damage index: a systematic literature review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013;43(3):352-361.

doi pubmed - Touma Z, Urowitz MB, Gladman DD. SLEDAI-2K for a 30-day window. Lupus. 2010;19(1):49-51.

doi pubmed - Bell CF, Ajmera MR, Meyers J. An evaluation of costs associated with overall organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States. Lupus. 2022;31(2):202-211.

doi pubmed - Schultze M, Garal-Pantaler E, Pignot M, Levy RA, Carnarius H, Schneider M, Gairy K. Clinical and economic burden of organ damage among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in a real-world setting in Germany. BMC Rheumatol. 2024;8(1):18.

doi pubmed - Taraborelli M, Cavazzana I, Martinazzi N, Lazzaroni MG, Fredi M, Andreoli L, Franceschini F, et al. Organ damage accrual and distribution in systemic lupus erythematosus patients followed-up for more than 10 years. Lupus. 2017;26(11):1197-1204.

doi pubmed - Arkema EV, Saleh M, Simard JF, Sjowall C. Epidemiology and damage accrual of systemic lupus erythematosus in central Sweden: a single-center population-based cohort study over 14 years from Ostergotland county. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023;5(8):426-432.

doi pubmed - Ghazali WSW, Daud SMM, Mohammad N, Wong KK. Slicc damage index score in systemic lupus erythematosus patients and its associated factors. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(42):e12787.

doi pubmed - Al-Shujairi A, Elbadawi F, Al-Saleh J, Hamouda M, Vasylyev A, Khamashta M. Literature review of lupus nephritis From the Arabian Gulf region. Lupus. 2023;32(1):155-165.

doi pubmed - Zivkovic V, Mitic B, Stamenkovic B, Stojanovic S, Dinic BR, Stojanovic M, Jurisic V. Analysis on the risk factors for organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a cross-sectional single-center experience. Sao Paulo Med J. 2019;137(2):155-161.

doi pubmed - Bonakdar ZS, Mohtasham N, Karimifar M. Evaluation of damage index and its association with risk factors in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16(Suppl1):S427-432.

pubmed - Zhang S, Ye Z, Li C, Li Z, Li X, Wu L, Liu S, et al. Chinese Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Treatment and Research Group (CSTAR) Registry XI: gender impact on long-term outcomes. Lupus. 2019;28(5):635-641.

doi pubmed - Conti F, Ceccarelli F, Perricone C, Leccese I, Massaro L, Pacucci VA, Truglia S, et al. The chronic damage in systemic lupus erythematosus is driven by flares, glucocorticoids and antiphospholipid antibodies: results from a monocentric cohort. Lupus. 2016;25(7):719-726.

doi pubmed - Petri M, Purvey S, Fang H, Magder LS. Predictors of organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus: the Hopkins Lupus Cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(12):4021-4028.

doi pubmed - Taraborelli M, Leuenberger L, Lazzaroni MG, Martinazzi N, Zhang W, Franceschini F, Salmon J, et al. The contribution of antiphospholipid antibodies to organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2016;25(12):1365-1368.

doi pubmed - Bertoli AM, Vila LM, Apte M, Fessler BJ, Bastian HM, Reveille JD, Alarcon GS, et al. Systemic lupus erythematosus in a multiethnic US Cohort LUMINA XLVIII: factors predictive of pulmonary damage. Lupus. 2007;16(6):410-417.

doi pubmed - Salah S, Lotfy HM, Mokbel AN, Kaddah AM, Fahmy N. Damage index in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in Egypt. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2011;9(1):36.

doi pubmed - Legge A, Doucette S, Hanly JG. Predictors of organ damage progression and effect on health-related quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(6):1050-1056.

doi pubmed - Apostolopoulos D, Kandane-Rathnayake R, Raghunath S, Hoi A, Nikpour M, Morand EF. Independent association of glucocorticoids with damage accrual in SLE. Lupus Sci Med. 2016;3(1):e000157.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.