| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, May 2025, pages 000-000

Kinesiophobia in Systemic Sclerosis: Relationship With Functional Status, Pulmonary Fibrosis, Depression, and Other Clinical Parameters

Canan Balamir Pehlivana, Mustafa Akif Sariyildizb, e, Remzi Cevikc, Serkan Erbaturd, Ibrahim Batmazc

aDepartment of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Siirt Training Research Hospital, Siirt, Turkey

bDepartment Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Uskudar University Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

cDepartment of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Dicle University Faculty of Medicine, Diyarbakir, Turkey

dDepartment of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Dicle University Faculty of Medicine, Diyarbakir, Turkey

eCorresponding Author: Mustafa Akif Sariyildiz, Department Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Uskudar University Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

Manuscript submitted February 9, 2025, accepted April 24, 2025, published online May 8, 2025

Short title: Kinesiophobia in Patients With SSc

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6202

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The aim of this study was to evaluate the levels of kinesiophobia and its relationship with functional status, quality of life, pulmonary involvement, depression, and other clinical parameters of the disease in patients with systemic sclerosis (SSc).

Methods: A total of 100 individuals (40 patients with SSc and 60 healthy controls) were included in the study. The Tampa scale was used to assess kinesiophobia. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to assess depression. Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SSc-HAQ) was used to assess functional status. Modified Rodnan skin score was used to assess skin thickness, and high-resolution computed tomography was used to assess lung fibrosis.

Results: The mean Tampa kinesiophobia score was significantly higher in patients with SSc compared to healthy controls. Depressive symptoms were present in 57.5% of patients with SSc. Disease duration, pain, fatigue, disease activity, functional status, pulmonary fibrosis, and depressive symptoms were correlated with kinesiophobia in patients with SSc.

Conclusion: There is an increased prevalence of kinesiophobia in patients with SSc, which seems to be more closely associated with disease duration, pain levels, and depressive symptoms.

Keywords: Systemic sclerosis; Kinesiophobia; Pulmonary fibrosis; Depression; Disease activity

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a chronic autoimmune disease affecting multiple organ systems, characterized by fibrous formation, especially in the skin and internal organs [1-3]. As with other autoimmune diseases, SSc is more common in females and peaks between 40 and 50 years of age. It has been reported that fatigue, skin deformities, pain, joint stiffness, changes in body image, and functional limitations are the most distressing symptoms in patients with SSc [2, 4, 5]. Fibrosis in SSc occurs as a result of vasculopathy and immune system activation. The fibrotic process is more pronounced in the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, heart, tendons, and endocrine glands. Fibrosis in involved organs increases morbidity and mortality and negatively impacts quality of life [1, 6].

Emotional stress in chronic diseases negatively affects kinesiophobia [7]. A recent systematic review reported that the ratio of depressive symptoms in patients with SSc ranged between 36% and 65% [8]. Patients with SSc are more prone to depression than patients with other chronic diseases due to chronic pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, deterioration in appearance, and disability [9, 10].

The term kinesiophobia or “fear of movement” was first used in 1990 by Kori et al for low back pain. They defined kinesiophobia as “fear and anxiety that develops against activity and physical movement, resulting from hypersensitivity and uncomfortable sensations due to painful or repetitive injury” [7]. In the long term, this can lead to disability, psychological problems, and deterioration in quality of life. This attitude is defined as fear-avoidance behavior, and in this case, the fear of pain causes more harm to the patient than the pain itself [11, 12].

There are few studies in the existing literature examining the relationship between rheumatic diseases and kinesiophobia. Studies conducted in patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) have shown that kinesiophobia is a significant issue in rheumatic diseases [13-16]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first study to demonstrate the relationship between kinesiophobia and SSc. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of kinesiophobia in patients with SSc and to determine the relationship between kinesiophobia and functional status, fatigue, pain, depression, pulmonary involvement, modified Rodnan skin score, and other clinical and biochemical parameters of the disease.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study groups

Patients who applied to the Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic of Dicle University Hospital between February 2022 and September 2022 and were followed up with a diagnosis of SSc according to the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 1980 classification criteria were included in the study. Forty patients aged 18 - 65 years with SSc were included in the study along with 60 healthy individuals with demographically similar characteristics as the control group. Individuals with any chronic disease such as diabetes, thyroid, heart or kidney failure, severe psychiatric disorders, and regular alcohol consumption were excluded from the study. The control group consisted of healthy volunteers among hospital employees matched for age and gender. This study was planned as a cross-sectional study and approved by the local ethics committee of Dicle University. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Measurement of clinical variables

Age, gender, height, weight, education level, duration of disease, cardiovascular findings, digital ulcers, Raynaud’s phenomenon, gastrointestinal findings (gastroesophageal reflux and dysphagia), and dyspnea were recorded. Mean pain and mean fatigue levels were recorded with a 100 mm visual analog scale (VAS). Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was determined by the Westergren method (mm/h) and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level was determined using nephelometry (mg/dL). Antinuclear antibody, anti-SCL70, and anticentromere levels were detected using the immunofluorescence method.

The diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) was evaluated by pulmonary function testing. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was used to evaluate pulmonary parenchymal fibrosis. Scans of HRCT were revealed using a 64-slice computed tomography (Philips, Brilliance 64) and evaluated to identify parenchymal pathologies. Scans were performed with 1 mm thick sections at 10 mm intervals.

Skin involvement of scleroderma was assessed with the help of the modified Rodnan skin score (mRSS). mRSS clinically assesses scleroderma of 17 body surface areas and assigns a specific thickness value to each area from 0 to 3: 0 = normal, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe (maximum score: 51). European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) Scleroderma Trials and Research Group (EUSTAR) criteria were used to measure disease activity [17].

EUSTAR scleroderma trial and investigational group criteria were used to measure disease activity. EUSTAR criteria for disease activity include mRSS score > 14 (score 1), scleroderma (score 0.5), worsening of skin involvement in the last month (score 2), fingertip ulcerations (score 0.5), worsening of vascular complaints in the last month (score 0.5), symmetrical swelling and tenderness of peripheral joints (score 0.5), DLCO less than 80% of the expected value (score 0.5), worsening heart or lung involvement in the last month (score 2), ESR > 30 (score 1.5), and hypocomplementemia (low C3 or C4). A total score of all parameters ≥ 3 indicates disease activity [18].

Measurement of physical functioning

Scleroderma Health Assessment Questionnaire (SSc-HAQ) was used to assess physical functioning. The SSc-HAQ is a widely used multisystem scale, especially for SSc. The SSc-HAQ scale includes five VAS questions that inquire about the severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon, digital ulcer, gastrointestinal and pulmonary respiratory symptoms, as well as the severity of the disease in general from the patient’s perspective [19].

Measurements of the psychological variables

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to assess depression in SSc patients. BDI is a Likert-type self-report questionnaire that assesses the level of depression based on responses to 21 questions [20]. In our study, a BDI score of 17 was selected as the recommended cut-off point for depression [21]. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the scale have previously been demonstrated to be satisfactory [22].

Tampa scale for kinesiophobia

The kinesiophobia levels of the patient and control groups were assessed using the Tampa scale for kinesiophobia. The scale consists of 17 items and includes movement/reinjury and fear-avoidance parameters. The total score ranges from 17 to 68. Higher scores indicate higher level of kinesiophobia. The items are scored on a four-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (score 1) to “strongly agree” (score 4). Four items (4, 8, 11, and 12) are reverse-coded. The total score ranges from 17 to 68, with higher scores indicating more severe kinesiophobia [23, 24].

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) version 22 package program. Categorical variables were presented as n (%) values, and continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The Chi-square test was used for the comparison of categorical variables between groups. Conformity of the variables to normal distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For paired comparisons, Student’s t-test was used for normally distributed variables while the Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-normally distributed variables. Pearson and Spearman correlation analyses were performed to assess correlations where appropriate. A stepwise method was used to construct the multivariate regression models with respect to the various dependent variables. A statistical significance level of P < 0.05 was used in all analyses.

| Results | ▴Top |

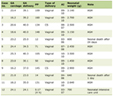

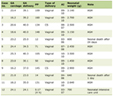

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients and healthy controls are listed in Table 1. Of the SSc patients, 92.5% were women, 49.9% were postmenopausal, and 87.5% were married. The mean age of the patient group was 50.2 years. The mean disease duration was 7.82 years. The mean Tampa kinesiophobia score was 48.4 in patients with SSc and 33.4 in healthy controls (P < 0.001). Depressive symptoms were present in 57.5% of SSc patients (Table 1). Correlation analysis revealed that disease duration, pain, fatigue, disease activity, functional status, pulmonary fibrosis, and depressive findings were associated with kinesiophobia in patients with SSc (P < 0.05). There was no correlation between kinesiophobia and age, BMI, mRSS, bowel disease, Raynoud’s phenomenon, digital ulcer, and laboratory parameters (Table 2). The multivariate regression analyses indicated that the Beck depression score and mean pain level were independently associated with the kinesiophobia (P < 0.01).

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Patients With SSc and Healthy Controls |

Click to view | Table 2. Correlation Between the Kinesiophobia Total Scores With the Clinical, Laboratory, Functional, and Psychological Characteristics in Patients With SSc |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study, the mean kinesiophobia score was significantly higher in SSc patients compared to healthy controls. This is the first study in the literature demonstrating the relationship between SSc and kinesiophobia. Previous studies have examined the prevalence of kinesiophobia in patients with RA [13], AS [14, 15], and SLE [16]. All of these studies showed that the existing rheumatic condition adversely affected kinesiophobia. This was associated with widespread muscle and joint pain, fatigue, sleep problems, psychological burden associated with the disease, morning stiffness, adverse effects related to polypharmacy, and active disease processes [25-29].

In the present study, a positive correlation was found between pain scores and disease activity and kinesiophobia, consistent with many previous studies. A positive correlation between disease activity and kinesiophobia was previously demonstrated in patients with RA and AS [13, 14]. Yentur et al reported higher levels of kinesiophobia in patients with SLE compared to healthy controls, but did not detect a relationship between pain and kinesiophobia [16]. Similarly, in another study conducted in AS patients, no relationship was found between kinesiophobia and pain [15]. The authors attributed this to the fact that the patients with SLE and AS included in the study were in remission, hence the already low levels of musculoskeletal pain in these patients.

It has been reported in many studies that the deterioration in functional status and quality of life negatively affects kinesiophobia in rheumatic diseases. In patients with AS, it has been shown that kinesiophobia is associated with deterioration in quality of life and functional status [14, 15]. The impact of functional disability on kinesiophobia was investigated in RA patients and it was determined that as physical functions deteriorate, emotional, social, and mental functions are also negatively affected and thus quality of life deteriorates [13]. In patients diagnosed with SLE, significant relationships were observed between kinesiophobia and the subscales of sleep, social isolation, and emotional reactions in quality of life assessments. However, no relationship was found between kinesiophobia and other parameters in these assessments [16]. Although the musculoskeletal system is affected in lupus patients, they usually present with milder joint involvement and less deformity, so there may not be an intercourse between kinesiophobia and other parameters of quality of life. However, deformities, especially in the joints of the hands and feet, are more prominent and devastating in patients with SSc. This may be the primary reason for the positive correlation between kinesiophobia and functional status in our patients.

Depression often accompanies inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Studies in patients with SLE reported depression rates between 41% and 51% [30]. In another study in which the psychological status of SSc patients was evaluated with BDI, a depressive state was detected at a rate of 62.5% [10]. In the present study, 57.5 % of the patients had mild to severe depression. In addition, it was found that as depression levels increased in SSc patients, kinesiophobia also increased. Similar to these findings, a relationship between kinesiophobia and depression was also found in patients with RA [22]. These results are consistent with the rates reported in the literature. Psychological problems such as anxiety and depression in these patients not only negatively affect social isolation but also contribute to the development of kinesiophobia by disrupting pain perception. When compared to studies conducted in other rheumatic diseases, the rate of depressed patients was higher in our study, which may be due to the more destructive effects of SSc. Our study revealed that depression negatively affects kinesiophobia in patients with SSc. Whether kinesiophobia is caused by depression or directly related to SSc is a more complex issue. We also demonstrated this relationship with regression analysis.

There are many studies evaluating fatigue in rheumatic diseases [10, 25-28]. Previous studies demonstrated increased levels of fatigue in SSc patients [10]. Similarly, fatigue is estimated to affect 53% of patients with AS [29]. However, this rate is reported to be between 40% and 80% in patients with RA [27]. Studies in patients with SLE reported that fatigue was one of the leading complaints in 53% to 80% of patients [30]. Previous studies have shown that increased levels of fatigue in patients with SSc may be associated with pain, depression, and sleep disturbance [10, 31, 32]. Consequently, a patient with increased fatigue may lose the will to move. In the present study, the level of fatigue was positively correlated with kinesiophobia.

There is no study in the literature demonstrating the relationship between pulmonary fibrosis and kinesiophobia in patients with SSc. However, previous studies reported a decrease in exercise tolerance in SSc patients, but also showed that exercise tolerance increased after pulmonary fibrosis regressed with medical treatment [33, 34]. Unlike other rheumatic diseases, SSc is characterized by excessive collagen production leading to vasculopathy and fibrosis, and lung involvement is common. This often presents as pulmonary vasculopathy due to interstitial lung disease (ILD) or pulmonary arterial hypertension [34]. In the present study, a correlation was found between pulmonary fibrosis and kinesiophobia. In this patient group, pulmonary fibrosis causes dyspnea, thus decreasing exercise tolerance. In the present study, 60% of the patients had pulmonary fibrosis. Higher rates of kinesiophobia in SSc patients may be related to the higher prevalence of pulmonary involvement and dyspnea in these patients.

There are certain limitations of the present study. It was a cross-sectional study and the number of patients was relatively small. Prospective studies with larger patient groups might better elucidate the relationship between SSc and kinesiophobia. Finally, a significant majority of our patients were female. Kinesiophobia in male patients diagnosed with SSc might present different clinical findings.

Conclusion

The significance of our study lies in being the first to assess kinesiophobia in SSc patients. Just like in other rheumatic diseases, regular exercise plays a crucial role in the rehabilitation of SSc patients due to its positive contribution to the musculoskeletal system. Evaluating kinesiophobia in these patients and attempting to address it, if present, can contribute to their rehabilitation. In conclusion, treating kinesiophobia in patients with SSc will contribute to improving both their physical functions and psychological well-being.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants who contributed to our study.

Financial Disclosure

The authors received no financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained.

Author Contributions

Canan Balamir Pehlivan and Serkan Erbatur collected the patient data. Mustafa Akif Sariyildiz wrote the article (introduction, methods, and discussion sections) and performed the statistical analyses. Ibrahim Batmaz and Remzi Cevik wrote the results section and performed tables.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

ACR: American College of Rheumatology; ANA: antinuclear antibody; AS: ankylosing spondylitis; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BMI: Body mass index; CRP: C-reactive protein; DLCO: diffusion capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; EUSTAR: European League Against Rheumatism Scleroderma Trials and Research Group; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; HRCT: high-resolution computed tomography; mRSS: modified Rodnan skin score; n: number of cases; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; SD: standard deviation; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; SSc: systemic sclerosis; VAS: visual analog scale

| References | ▴Top |

- Allanore Y, Simms R, Distler O, et al. Systemic sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2015;23:1.

- Desbois AC, Cacoub P. Systemic sclerosis: An update in 2016. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(5):417-426.

doi pubmed - Nikpour M, Stevens WM, Herrick AL, Proudman SM. Epidemiology of systemic sclerosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(6):857-869.

doi pubmed - Roberts-Thomson PJ, Walker JG, Lu TY, Esterman A, Hakendorf P, Smith MD, Ahern MJ. Scleroderma in South Australia: further epidemiological observations supporting a stochastic explanation. Intern Med J. 2006;36(8):489-497.

doi pubmed - Le Guern V, Mahr A, Mouthon L, Jeanneret D, Carzon M, Guillevin L. Prevalence of systemic sclerosis in a French multi-ethnic county. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43(9):1129-1137.

doi pubmed - Distler JH, Jungel A, Pileckyte M, Zwerina J, Michel BA, Gay RE, Kowal-Bielecka O, et al. Hypoxia-induced increase in the production of extracellular matrix proteins in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(12):4203-4215.

doi pubmed - Kori SH, Miller RP, Todd D. Kinesiophobia: A new view of chronic pain behaviour. Pain omanage. 1990;3:35-43.

- Thombs BD, Taillefer SS, Hudson M, Baron M. Depression in patients with systemic sclerosis: a systematic review of the evidence. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(6):1089-1097.

doi pubmed - Evans DL, Charney DS, Lewis L, Golden RN, Gorman JM, Krishnan KR, Nemeroff CB, et al. Mood disorders in the medically ill: scientific review and recommendations. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(3):175-189.

doi pubmed - Sariyildiz MA, Batmaz I, Budulgan M, et al. Sleep quality in patients with systemic sclerosis: relationship between the clinical variables, depressive symptoms, functional status, and the quality of life. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2680-2689.

- Picavet HS, Vlaeyen JW, Schouten JS. Pain catastrophizing and kinesiophobia: predictors of chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156(11):1028-1034.

doi pubmed - Leeuw M, Goossens ME, Linton SJ, Crombez G, Boersma K, Vlaeyen JW. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30(1):77-94.

doi pubmed - Baysalhan Ozturk I, Garip Y, Sivas F, Parlak Ozden M, Bodur H. Kinesiophobia in rheumatoid arthritis patients: Relationship with quadriceps muscle strength, fear of falling, functional status, disease activity, and quality of life. Arch Rheumatol. 2021;36(3):427-434.

doi pubmed - Selcuk MA, Cakit MO, Aslan SG, et al. The effect of cynesiophobia on disease activity and functional status in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ankara Egt Ars Hast Derg. 2018;51:180-185.

- Oskay D, Tuna Z, Duzgun I, Elbasan B, Yakut Y, Tufan A. Relationship between kinesiophobia and pain, quality of life, functional status, disease activity, mobility, and depression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47(5):1340-1347.

doi pubmed - Baglan Yentur S, Karatay S, Oskay D, Tufan A, Kucuk H, Haznedaroglu S. Kinesiophobia and related factors in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Turk J Med Sci. 2019;49(5):1324-1331.

doi pubmed - Clements P, Lachenbruch P, Siebold J, White B, Weiner S, Martin R, Weinstein A, et al. Inter and intraobserver variability of total skin thickness score (modified Rodnan TSS) in systemic sclerosis. J Rheumatol. 1995;22(7):1281-1285.

pubmed - Valentini G, D'Angelo S, Della Rossa A, Bencivelli W, Bombardieri S. European Scleroderma Study Group to define disease activity criteria for systemic sclerosis. IV. Assessment of skin thickening by modified Rodnan skin score. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(9):904-905.

doi pubmed - Ostojic P, Damjanov N. The scleroderma Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ). A new self-assessment questionnaire for evaluation of disease status in patients with systemic sclerosis. Z Rheumatol. 2006;65(2):168-175.

doi pubmed - Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561-571.

doi pubmed - Lasa L, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Diez-Manrique FJ, Dowrick CF. The use of the Beck Depression Inventory to screen for depression in the general population: a preliminary analysis. J Affect Disord. 2000;57(1-3):261-265.

doi pubmed - Hisli N. A study on the validity of beck depression inventory. J Psychol. 1988;6:118-122.

- Tunca Yilmaz Y, Yakut Y, Uygur F, et al. Turkish version of the Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia and its test-retest reliability. Turk J Physiother Rehabil. 2011;22:44-49.

- Acar S, Savci S, Keskinoglu P, Akdeniz B, Ozpelit E, Ozcan Kahraman B, Karadibak D, et al. Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia for Heart Turkish Version Study: cross-cultural adaptation, exploratory factor analysis, and reliability. J Pain Res. 2016;9:445-451.

doi pubmed - Wouters EJ, van Leeuwen N, Bossema ER, Kruize AA, Bootsma H, Bijlsma JW, Geenen R. Physical activity and physical activity cognitions are potential factors maintaining fatigue in patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(5):668-673.

doi pubmed - Isenber DA, Snaith ML. Muscle Disease in systemic lupus erythematosus: a study of its nature, frequency and cause. J Rheumatol. 1981;8(6):917-924.

pubmed - Loof H, Demmelmaier I, Henriksson EW, Lindblad S, Nordgren B, Opava CH, Johansson UB. Fear-avoidance beliefs about physical activity in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2015;44(2):93-99.

doi pubmed - Volkmann ER, Grossman JM, Sahakian LJ, Skaggs BJ, FitzGerald J, Ragavendra N, Charles-Schoeman C, et al. Low physical activity is associated with proinflammatory high-density lipoprotein and increased subclinical atherosclerosis in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(2):258-265.

doi pubmed - van Genderen S, van den Borne C, Geusens P, van der Linden S, Boonen A, Plasqui G. Physical functioning in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: comparing approaches of experienced ability with self-reported and objectively measured physical activity. J Clin Rheumatol. 2014;20(3):133-137.

doi pubmed - Palagini L, Mosca M, Tani C, Gemignani A, Mauri M, Bombardieri S. Depression and systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Lupus. 2013;22(5):409-416.

doi pubmed - Thombs BD, Hudson M, Bassel M, Taillefer SS, Baron M, Canadian Scleroderma Research G. Sociodemographic, disease, and symptom correlates of fatigue in systemic sclerosis: evidence from a sample of 659 Canadian Scleroderma Research Group Registry patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(7):966-973.

doi pubmed - Thombs BD, Bassel M, McGuire L, Smith MT, Hudson M, Haythornthwaite JA. A systematic comparison of fatigue levels in systemic sclerosis with general population, cancer and rheumatic disease samples. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2008;47(10):1559-1563.

doi pubmed - Wells AU, Steen V, Valentini G. Pulmonary complications: one of the most challenging complications of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:40-44.

- Vaiarello V, Schiavetto S, Foti F, Gigante A, Iannazzo F, Paone G, Palange P, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil improves exercise tolerance in systemic sclerosis patients with interstitial lung disease: a pilot study. Rheumatol Ther. 2020;7(4):1037-1044.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.