| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 17, Number 12, December 2025, pages 726-732

Molecular and Immune Microenvironmental Changes Across Endometrial Lesions: A Comprehensive Immunohistochemical and Clinical Analysis of Progression From Benignity to Carcinoma

Beka Metrevelia, Tinatin Gaguaa, Davit Gaguaa, Shota Kepuladzea, b, George Burkadzea

aDepartment of Molecular Pathology, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi, Georgia

bCorresponding Author: Shota Kepuladze, Department of Molecular Pathology, Tbilisi State Medical University, Tbilisi, Georgia

Manuscript submitted August 14, 2025, accepted October 30, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: Endometrial Microenvironment Changes

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6342

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Adenomyosis and endometriosis are estrogen-driven disorders with a recognized potential for malignant transformation, particularly through atypical endometriosis. The molecular and immune mechanisms underlying this progression remain incompletely understood. However, clinical factors such as age, comorbidities, and hormonal therapy can also influence lesion behavior. The objectives were to comprehensively evaluate hormonal, proliferative-apoptotic, cell-cycle, and immune-microenvironmental alterations across the spectrum of endometrial lesions and to assess the impact of prior endometrial hyperplasia and associated clinical parameters.

Methods: Seventy-seven formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded cases were stratified into five groups: eutopic endometrium (n = 17), adenomyosis (n = 27), typical endometriosis (n = 16), atypical endometriosis (n = 10), and endometriosis-associated carcinoma (n = 24). Immunohistochemical analysis included estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, Ki67, BCL2, P53, cyclin D1, CDK4, P16, FOXP3, CD68, and CD163. Clinical variables including age, comorbidities, and medication history were integrated into statistical analysis. Marker expression was quantified semi-quantitatively, and clinical associations with prior endometrial hyperplasia were evaluated using Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results: Cyclin D1, CDK4, and P16 expression progressively increased from benign lesions to carcinoma (P < 0.001). FOXP3+ T cells and CD163+ M2 macrophages accumulated in atypical endometriosis and carcinoma, indicating an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Patients with prior atypical endometrial hyperplasia demonstrated significantly higher expression of proliferative (cyclin D1, CDK4, and P16) and immune-suppressive markers (FOXP3 and CD163) and a 66% progression to carcinoma. Clinical background factors were statistically adjusted and did not alter the overall progression trend.

Conclusion: The stepwise evolution from benign endometrial lesions to carcinoma is driven by coordinated proliferative and immune microenvironmental shifts, potentiated by a history of atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Integrating immunohistochemical and clinical risk factors may enhance early identification and surveillance of patients at high risk for endometriosis-associated carcinoma.

Keywords: Endometriosis; Adenomyosis; Endometriosis-associated carcinoma; CD163; Endometrial hyperplasia; FOXP3; P16; CDK4; Cyclin D1

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Adenomyosis and endometriosis are gynecologic disorders characterized by the aberrant presence of endometrial tissue outside its normal location, either within the myometrium or extrauterine sites [1]. Although historically considered benign, increasing evidence highlights their complex biological behavior, including invasiveness, proliferation, and, in some cases, progression to malignancy. Atypical endometriosis, in particular, has been proposed as a premalignant condition, mainly linked to the development of ovarian clear cell and endometrioid carcinomas [2].

The pathogenesis underlying the progression from benign to malignant ectopic endometrial lesions remains poorly elucidated. Hormonal dysregulation, notably the altered expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors (ER and PR), is critical in disease maintenance and progression [3]. Additionally, proliferative and apoptotic imbalance, reflected in markers such as Ki67, BCL2, and P53, is implicated in endometriosis-associated neoplastic transformation [4, 5]. Dysregulation of the cell cycle machinery, including overactivation of cyclin D1 and CDK4 and abnormalities in P16 expression, further contributes to the loss of cellular control and oncogenesis [6].

Chronic inflammation and immune evasion represent another crucial axis in disease evolution. Infiltrating macrophages (CD68+) and the polarization toward immunosuppressive M2 macrophages (CD163+) reshape the microenvironment to favor survival and proliferation of aberrant cells. Similarly, the expansion of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells within lesions reflects the establishment of local immune tolerance, a hallmark of tumor progression [7].

While much research has focused on molecular alterations within endometriotic tissues, the clinical impact of the endometrial background, particularly prior endometrial hyperplasia with or without atypia, has not been fully integrated into progression models [8]. Given that endometrial hyperplasia with atypia is a known precursor to endometrial carcinoma, its presence in patients with endometriosis or adenomyosis may signify an increased risk for malignant transformation, even at ectopic sites [9].

This study aimed to identify molecular and immune-microenvironmental transitions along the benign-to-malignant continuum of endometrial lesions, with cyclin D1 being chosen as the primary endpoint marker. Normal endometrium and adenomyosis were included as internal reference tissues to contextualize ectopic and malignant changes. Moreover, we assessed the association of prior endometrial hyperplasia with current lesion type and molecular profiles, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the clinical and biological pathways underpinning progression from benignity to carcinoma in endometriosis-associated lesions.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

This retrospective study, conducted between 2018 and 2024, meticulously collected and analyzed 77 cases from the Diagnostic Research and Scientific Laboratory archives at Tbilisi State Medical University (TSMU). The study population was carefully divided into five groups: eutopic endometrium (n = 17), ectopic endometrium in adenomyosis (n = 27), typical endometriosis (n = 16), atypical endometriosis (n = 10), and endometriosis-associated carcinoma (n = 24).

Inclusion criteria were: availability of complete clinical data, well-preserved formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, and confirmed diagnosis within one of five predefined histologic categories. Exclusion criteria were: poor preservation, cautery artifacts, glandular neoplasia, or incomplete records. Complete clinical data were thoroughly examined, including patient age, type of surgical specimen, hormonal therapy status, menstrual status, and detailed clinical history. This comprehensive approach ensures the reliability and robustness of our findings. Typical endometriosis was defined as endometrial gland-stromal foci lacking cytologic atypia. Atypical endometriosis exhibited epithelial crowding, nuclear hyperchromasia, and loss of polarity. Endometriosis-associated carcinoma was diagnosed when carcinoma was contiguous with endometriotic foci showing transitional morphology. All endometriotic and carcinoma cases derived from pelvic or ovarian resections; eutopic and adenomyotic tissues were from uterine specimens. Follow-up after initial hyperplasia diagnosis ranged 2 - 6 years; cases were subclassified as hyperplasia with or without atypia.

FFPE tissue blocks were sectioned at 4-µm thickness and subjected to immunohistochemical analysis. All staining procedures were performed using the fully automated Leica Bond-III immunostaining system (Leica Biosystems, Germany) according to standardized protocols. Primary antibodies used for immunohistochemical analysis included ER (clone SP1), PR (clone 16), Ki67 (clone MIB-1), BCL2 (clone 124), P53 (clone DO-7), cyclin D1 (clone EP12), CDK4 (clone DCS-31), P16 (clone E6H4), FOXP3 (clone 236A/E7), CD68 (clone PG-M1), and CD163 (clone 10D6), all manufactured by Leica Biosystems.

For each case, immunostaining was evaluated at × 400 magnification across at least five randomly selected high-power fields. The percentage of positive epithelial cells was recorded for epithelial markers (ER, PR, Ki67, BCL2, P53, cyclin D1, CDK4, and P16). For immune markers (FOXP3, CD68, and CD163), the percentage of positive stromal immune cells was determined separately, focusing on hotspot areas with the highest immune cell density. Marker expression was quantified semi-quantitatively and recorded as a continuous percentage.

Cases were analyzed according to their current histologic diagnosis and stratified based on clinical history of prior endometrial hyperplasia (without atypia or with atypia). For cases with a history of hyperplasia with atypia, particular attention was given to evaluating whether there was an associated increase in markers indicative of proliferative activity, cell cycle deregulation, and immune suppression.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences between groups were assessed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and pairwise comparisons with the Mann-Whitney U-test where appropriate. Associations between clinical history and immunohistochemical marker expression were evaluated using non-parametric correlation and multivariable tests integrating age, comorbidities, and medication status. A post hoc power analysis for cyclin D1 differences across groups yielded power = 0.87 (α = 0.05).

As this was a retrospective study on anonymized archival materials, formal ethical committee approval was not required under institutional guidelines; however, all procedures were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of Tbilisi State Medical University and the Declaration of Helsinki.

| Results | ▴Top |

Clinical characteristics

The study cohort included 77 cases with a mean age of 45.2 ± 7.1 years (30 to 55 years). Seventeen cases represented eutopic endometrium obtained from curettage specimens, 27 cases were diagnosed as ectopic endometrium within adenomyotic foci, 16 cases as typical endometriosis, 10 cases as atypical endometriosis, and 24 cases as endometriosis-associated carcinoma. Premenopausal status predominated in eutopic endometrium and typical endometriosis groups, while perimenopausal and postmenopausal states were more common in atypical endometriosis and carcinoma groups. Hormonal therapy was documented in 18 cases, predominantly in patients with atypical endometriosis and carcinoma. Table 1 summarizes demographic and clinical parameters used in subsequent correlation analysis. Comorbidities were most frequent in carcinoma cases, while hormonal therapy predominated in atypical endometriosis.

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population by Group |

Overall, 18 cases had a clinical history of endometrial hyperplasia, and six cases exhibited hyperplasia with atypia. Notably, four of these six patients subsequently developed endometriosis-associated carcinoma, suggesting a possible link between antecedent atypical hyperplasia and malignant transformation at ectopic sites.

Immunohistochemical marker expression across lesions

Quantitative results for all groups are summarized in Table 2.

Click to view | Table 2. Marker Expression Across All Histological Groups |

Proliferative and cell cycle regulatory markers

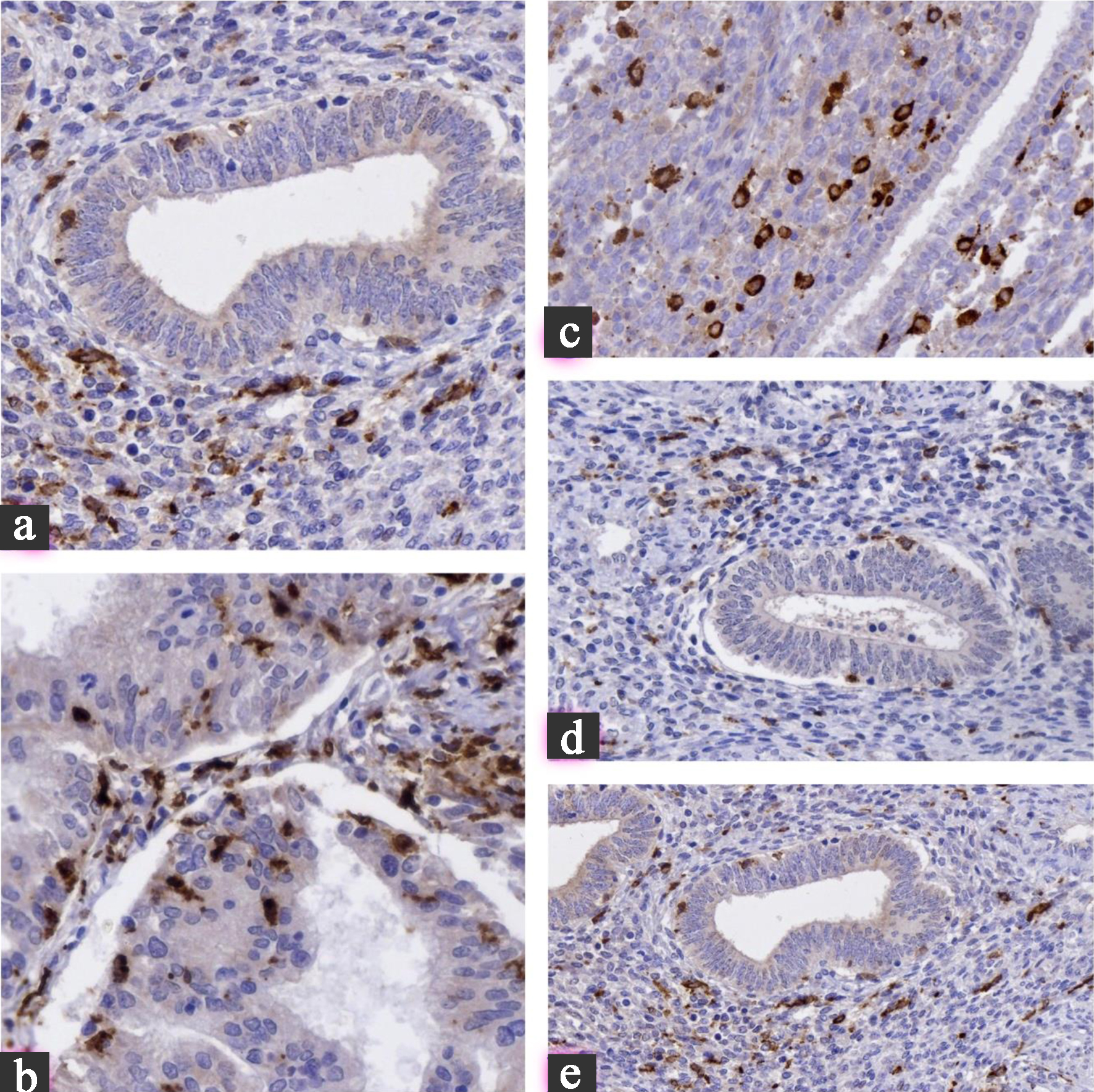

Cyclin D1 expression exhibited a progressive and statistically significant increase across the studied groups. The mean expression rose from 2.5±1.5% in eutopic endometrium, 13.0 ± 5.0% in adenomyosis, 21.0±7.0% in typical endometriosis, 36.0±8.0% in atypical endometriosis, to 41.0±10.0% in endometriosis-associated carcinoma (P < 0.001, Kruskal-Wallis test). Similarly, CDK4 and P16 expressions followed a comparable pattern, with significantly elevated levels in atypical endometriosis and carcinoma compared to benign lesions (P < 0.001). Representative immunohistochemical staining patterns are shown in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Distribution of immune microenvironment markers FOXP3, CD68, and CD163. |

Post hoc pairwise comparisons confirmed significant differences between carcinoma and eutopic endometrium (P < 0.001 for cyclin D1, CDK4, and P16), and between atypical endometriosis and typical endometriosis (P = 0.012).

Immune microenvironment markers

FOXP3 expression, reflecting regulatory T-cell infiltration, demonstrated an increasing trend from benign to malignant lesions. Mean FOXP3 expression rose from 3.0 ± 1.0% in eutopic endometrium to 26.0 ± 7.0% in carcinoma (P = 0.002). CD68, indicative of general macrophage infiltration, increased from 4.0±2.0% in eutopic endometrium to 38.0±8.0% in carcinoma. Similarly, CD163, representing M2 macrophage polarization, rose from 3.0±1.5% to 32.0±7.0% across the groups (P = 0.001). These trends are illustrated in Figure 2.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Marker expression in cases with and without prior endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. |

Pairwise comparisons demonstrated significantly higher FOXP3 and CD163 levels in atypical endometriosis compared to typical endometriosis (P = 0.014 and P = 0.017, respectively), supporting the concept of an evolving immunosuppressive microenvironment.

Hormonal and apoptotic markers

ER and PR expressions were highest in eutopic endometrium (mean ER 80-90%) and adenomyosis but gradually declined in typical and atypical endometriosis and reached their lowest in carcinoma cases (mean ER 20-30%, P < 0.001). Ki67 proliferative index, conversely, increased gradually, correlating with disease severity. Representative staining examples are provided in Figure 3.

Click for large image | Figure 3. (a) Cyclin D1: minimal nuclear expression in eutopic endometrium, moderate in atypical endometriosis, and strong diffuse positivity in carcinoma. (b) P16: weak/focal staining in benign lesions transitions to block-like, diffuse expression in carcinoma, reflecting cell cycle deregulation. (c) FOXP3: nuclear staining of regulatory T cells progressively increases, highlighting the evolving immunosuppressive microenvironment. (d) CD163: cytoplasmic/membranous staining in stromal macrophages intensifies from benign lesions to carcinoma, indicating M2 polarization. (e) Ki67: low nuclear proliferation index in eutopic endometrium and adenomyosis, sharply increasing in atypical endometriosis and carcinoma. All images are at × 400 magnification. |

BCL2 expression showed a modest decrease across groups, while P53 accumulation became more frequent and intense in atypical endometriosis and carcinoma, suggesting a shift towards dysregulated apoptotic control.

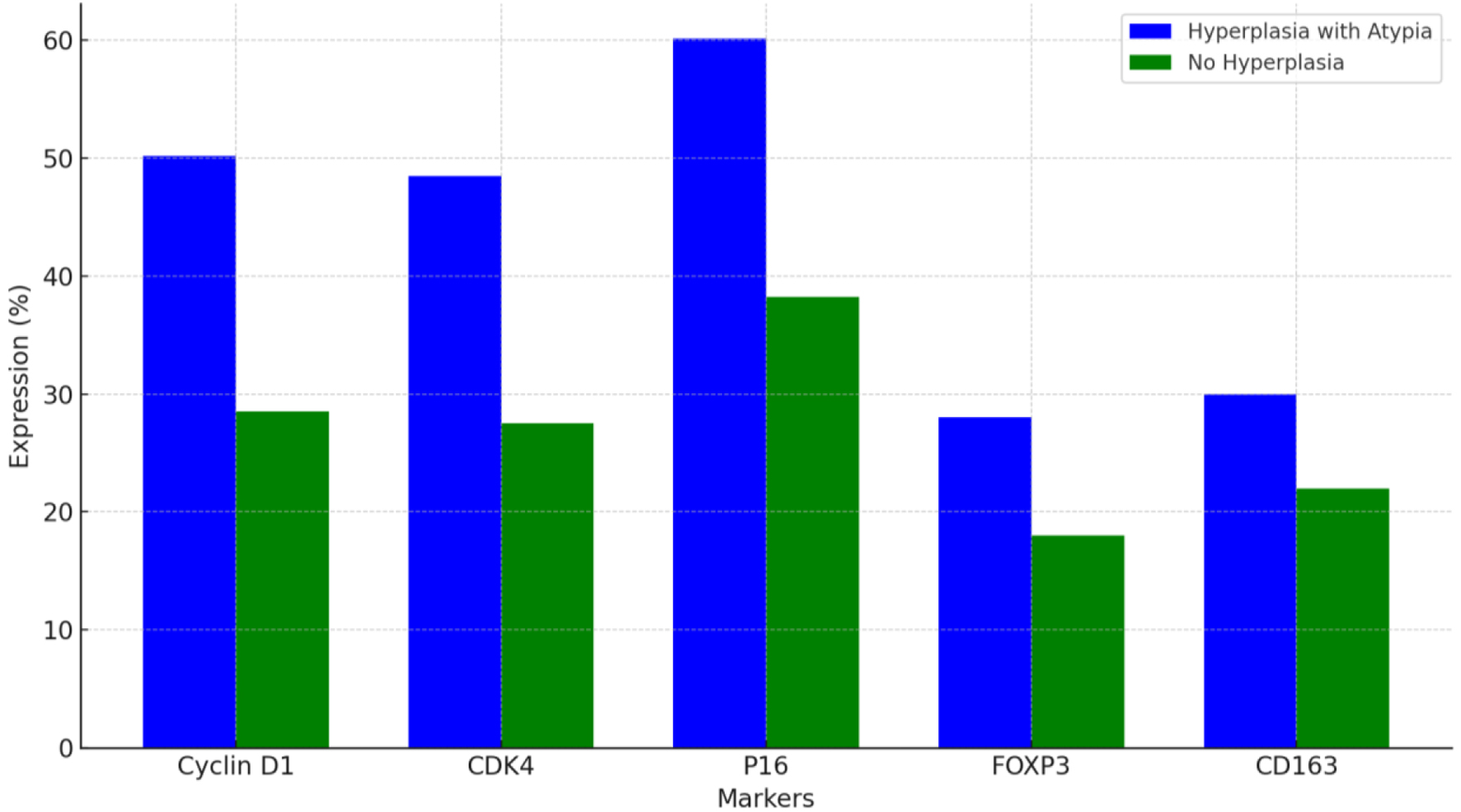

Impact of prior endometrial hyperplasia with atypia

Cases with a clinical history of endometrial hyperplasia with atypia exhibited significantly higher expressions of cyclin D1 (mean 50.2±9.0%), CDK4 (48.5±7.5%), and P16 (60.1±8.0%) compared to cases without such history (mean cyclin D1: 28.5±8.5%, P = 0.021; mean CDK4: 27.5±7.0%, P = 0.018; mean P16: 38.2±7.5%, P = 0.015). FOXP3 and CD163 expressions were also elevated in these cases (P = 0.028 and P = 0.032, respectively).

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This study provides a comprehensive immunohistochemical and clinical analysis of endometrial lesions ranging from eutopic endometrium through adenomyosis, typical and atypical endometriosis, culminating in endometriosis-associated carcinoma. Although subgroup numbers were modest, particularly for atypical endometriosis and hyperplasia with atypia, statistical power exceeded 0.8, supporting validity. Our findings confirm a progressive accumulation of molecular and immune alterations across this spectrum, supporting the notion of a stepwise biological evolution from benignity to malignancy. Patients were divided by prior hyperplasia status (with vs. without atypia) to examine molecular correlates rather than longitudinal outcomes. Systemic comorbidities and medications, especially endocrine and metabolic disorders, may modulate immune-microenvironmental behavior; their inclusion slightly refined statistical correlations but did not alter main trends.

Cyclin D1, CDK4, and P16, critical regulators of the G1-S phase transition, demonstrated progressive overexpression correlating with increasing histologic atypia and malignancy. This aligns with previous observations that cyclin D1 and CDK4 deregulation play pivotal roles in endometriosis-associated neoplastic transformation by promoting uncontrolled proliferation and bypassing cell cycle checkpoints [10]. The significant upregulation of P16 in atypical endometriosis and carcinoma is consistent with P16 acting paradoxically as a marker of oncogenic stress in advanced lesions, despite its traditional role as a tumor suppressor [11].

Importantly, immune microenvironment remodeling was evident in our analysis. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and CD68+ and CD163+ macrophages progressively accumulated from benign to malignant lesions. These findings confirm that immunosuppressive mechanisms, characterized by increased Treg infiltration and M2 macrophage polarization, facilitate immune evasion and support malignant progression in endometriosis [7]. The significant increase in CD163 expression, especially in the context of atypical endometriosis and carcinoma, indicates a transition towards an inflammatory environment characterized by both immunosuppressive properties and tumor promotion. This underscores the potential importance of macrophage markers as prognostic indicators.

Hormonal receptor expression patterns mirrored those reported in the literature, with declining ER and PR expression across disease progression. The loss of hormonal responsiveness may signify increased lesion autonomy and resistance to hormonal therapies, an important clinical implication [12]. The observed increase in Ki67 and aberrant P53 accumulation further underscores the proliferative drive and genomic instability accompanying malignant transformation [13].

This study’s novel and clinically significant finding was the association between prior endometrial hyperplasia with atypia and subsequent development of endometriosis-associated carcinoma. Approximately 66% of cases with prior atypical hyperplasia evolved to carcinoma, exhibiting significantly higher expressions of cyclin D1, CDK4, P16, and immunosuppressive markers. While prior studies have acknowledged the malignant potential of atypical endometriosis itself, few have explored the compounded risk contributed by antecedent uterine pathology. Our data suggest that a history of atypical hyperplasia may prime the endometrial microenvironment, both eutopic and ectopic, for neoplastic transformation.

Our study presents several strengths, including the integration of various immunohistochemical pathways - hormonal, proliferative, apoptotic, cell cycle, and immune - and their correlation with comprehensive clinical histories. However, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. The retrospective design constrains the capacity to draw causal inferences, and the substantial sample size in a single-center study may limit the power of subgroup analyses. Furthermore, while immunohistochemistry delivers important insights at the protein level, validating this with molecular genetics (such as sequencing for PTEN, ARID1A, or PIK3CA mutations) would enhance the mechanistic understanding. Nevertheless, our findings robustly support a model in which molecular changes and shifts in the immune microenvironment collaborate to facilitate the progression from benign endometrial lesions to carcinoma. Furthermore, the clinical history of endometrial hyperplasia with atypia emerges as a significant predictor of malignant risk, underscoring the necessity for enhanced surveillance strategies within this patient population.

Future multicenter prospective studies combining molecular sequencing and broader cohorts are warranted.

Conclusions

This integrated clinical-immunohistochemical study highlights coordinated proliferative and immune shifts underlying the continuum from benignity to carcinoma, emphasizing the compounding risk associated with prior atypical hyperplasia. Significant upregulation of cyclin D1, CDK4, and P16 expression, along with an increasing burden of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells and CD163+ M2 macrophages, characterizes the transition from benign to malignant disease. Hormonal receptor loss and proliferative-apoptotic imbalances further contribute to this progression.

Significantly, the presence of prior endometrial hyperplasia with atypia was associated with significantly higher expressions of proliferative and immune suppression markers and a greater risk of malignant transformation. This finding suggests that a hyperplastic background may instigate neoplastic evolution in ectopic and endometrial tissues. Although the study provides valuable insights into the immunohistochemical dimensions of endometriosis-related carcinogenesis, it is predicated solely on protein-level assessments. Further molecular genetic research is imperative to validate and expand upon these observations. Nevertheless, our findings underscore significant biological pathways and clinical risk factors that could serve as early indicators of malignant transformation, indicating potential strategies for risk assessment, monitoring, and future treatment approaches.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff of the Diagnostic Research and Scientific Laboratory, Tbilisi State Medical University, for their technical assistance.

Financial Disclosure

No funding was received for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

This was a retrospective study using anonymized FFPE samples; patient consent was waived according to institutional policy.

Author Contributions

Beka Metreveli: data collection and histopathological review; and final approval of the manuscript. Tinatin Gagua: IHC evaluation and statistical analysis; data collection and histopathological review. Davit Gagua: data collection and histopathological review; IHC evaluation and statistical analysis. Shota Kepuladze: conceptualization, manuscript drafting, and correspondence; IHC evaluation and statistical analysis. George Burkadze: supervision, critical review, and final approval of the manuscript; IHC evaluation and statistical analysis.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

CD163: M2 macrophage marker; CD68: pan-macrophage marker; ER: estrogen receptor; FFPE: formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; FOXP3: forkhead box protein P3; HPF: high-power field; IHC: immunohistochemistry; MVD: microvessel density; PR: progesterone receptor; SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

| References | ▴Top |

- Zhai J, Vannuccini S, Petraglia F, Giudice LC. Adenomyosis: mechanisms and pathogenesis. Semin Reprod Med. 2020;38(2-03):129-143.

doi pubmed - Modesitt SC, Tortolero-Luna G, Robinson JB, Gershenson DM, Wolf JK. Ovarian and extraovarian endometriosis-associated cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(4):788-795.

doi pubmed - Bulun SE, Cheng YH, Pavone ME, Xue Q, Attar E, Trukhacheva E, Tokunaga H, et al. Estrogen receptor-beta, estrogen receptor-alpha, and progesterone resistance in endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28(1):36-43.

doi pubmed - Goumenou A, Panayiotides I, Matalliotakis I, Vlachonikolis I, Tzardi M, Koumantakis E. Bcl-2 and Bax expression in human endometriotic and adenomyotic tissues. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;99(2):256-260.

doi pubmed - Radha G, Raghavan SC. BCL2: A promising cancer therapeutic target. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2017;1868(1):309-314.

doi pubmed - Berbic M, Schulke L, Markham R, Tokushige N, Russell P, Fraser IS. Macrophage expression in endometrium of women with and without endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(2):325-332.

doi pubmed - Fan D, Wang X, Shi Z, Jiang Y, Zheng B, Xu L, Zhou S. Understanding endometriosis from an immunomicroenvironmental perspective. Chin Med J (Engl). 2023;136(16):1897-1909.

doi pubmed - Wheeler DT, Bristow RE, Kurman RJ. Histologic alterations in endometrial hyperplasia and well-differentiated carcinoma treated with progestins. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(7):988-998.

doi pubmed - Kurman RJ, Kaminski PF, Norris HJ. The behavior of endometrial hyperplasia. A long-term study of "untreated" hyperplasia in 170 patients. Cancer. 1985;56(2):403-412.

doi pubmed - Szymanski M, Bonowicz K, Antosik P, Jerka D, Glowacka M, Soroka M, Steinbrink K, et al. Role of cyclins and cytoskeletal proteins in endometriosis: insights into pathophysiology. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16(4).

doi pubmed - Bartiromo L, Schimberni M, Villanacci R, Mangili G, Ferrari S, Ottolina J, Salmeri N, et al. A systematic review of atypical endometriosis-associated biomarkers. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(8).

doi pubmed - Sampson JA. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1927;14(4):422-469.

- Bulun SE, Monsivais D, Kakinuma T, Furukawa Y, Bernardi L, Pavone ME, Dyson M. Molecular biology of endometriosis: from aromatase to genomic abnormalities. Semin Reprod Med. 2015;33(3):220-224.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.