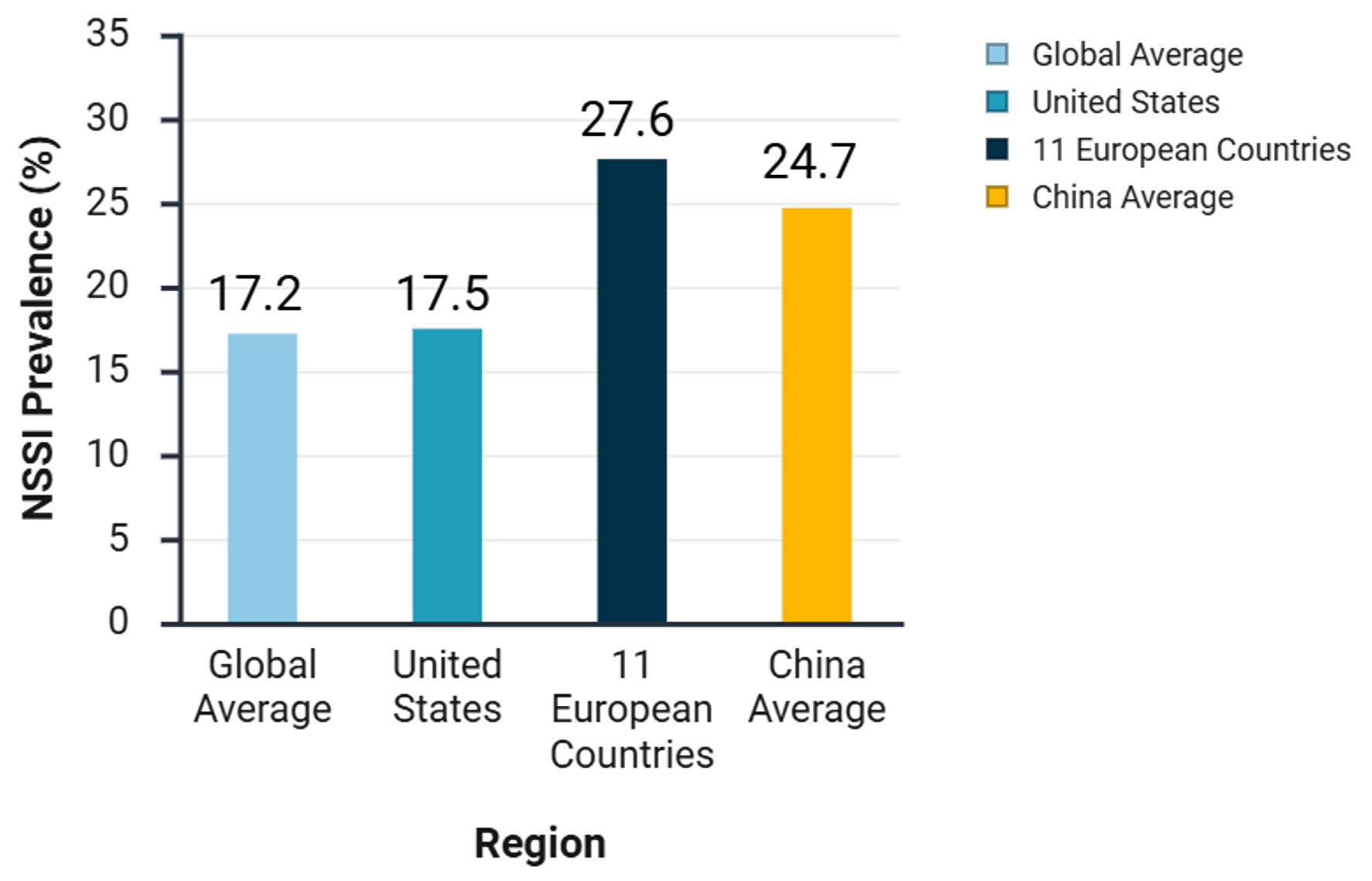

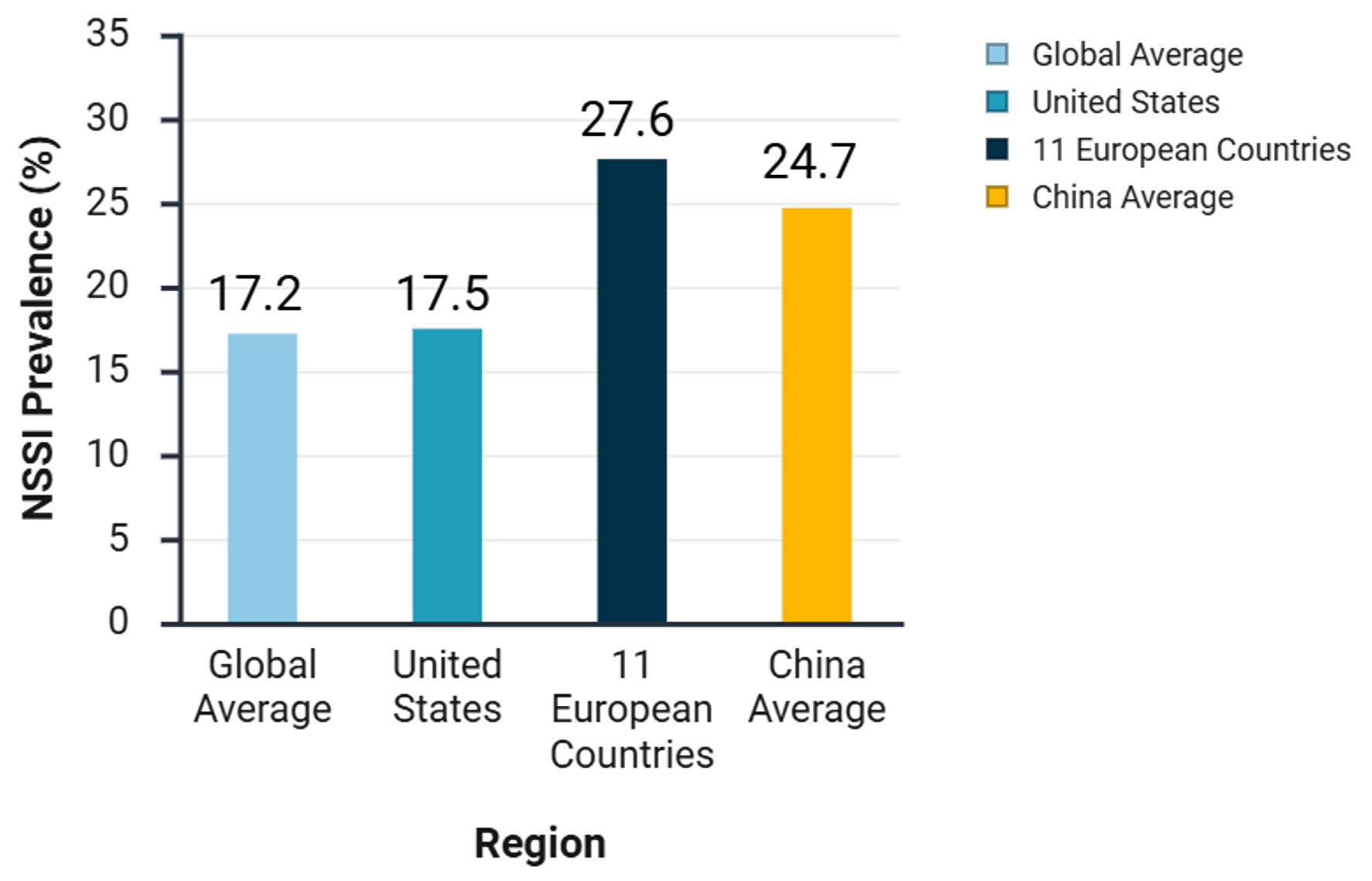

Figure 1. Prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) among adolescents in different regions.

| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Review

Volume 17, Number 10, October 2025, pages 537-549

Non-Suicidal Self-Injury: Pain Addiction Mechanisms, Neurophysiological Signatures, and Therapeutic Advances

Figures

Table

| Treatment category | Specific interventions | Mechanism of action/core processes | Evidence strength/efficacy | Precautions/side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI: non-suicidal self-injury; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI: serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. | ||||

| Psychotherapy | Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) | Training in emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, mindfulness; stage-based model | Strong evidence; significant reduction in self-injury frequency (70% reduction in studies); sustained effects; improves emotion regulation and social adaptation; reduces dropout rates | Requires structured, multi-modal implementation; demands therapist training and team support. |

| Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) | Enhance psychological flexibility (acceptance, cognitive defusion, present moment awareness, values, committed action) | Innovative approach: studies show reduction in self-injury ideation; improved quality of life; promotion of positive behavioral changes. | Requires active patient participation and practice. | |

| Physical interventions | Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) | Electromagnetic induction modulates cortical excitability, neuroplasticity and neurotransmitters; normalizes abnormal neural circuits | Noninvasive, minimal side effects; rapid reduction in self-injury frequency/severity (within 2 weeks); enhanced efficacy when combined with medication. | Requires specialized equipment and operators; long-term efficacy evidence is still accumulating. |

| Pharmacotherapy | Opioid receptor antagonists (naltrexone, buprenorphine) | Blocks opioid receptors and affects pain-reward circuit. | Potential for specific populations (impulsive, emotional dysregulation); low doses may be effective but requires more evidence. | Naltrexone: nausea, headache, may precipitate withdrawal; buprenorphine: avoid combination with benzodiazepines (respiratory depression risk). |

| Mood stabilizers (lithium) | Mechanisms not fully understood, may involve endogenous opioid system; “anti-suicidal” effect in bipolar disorder. | Preventive effect on suicidal behavior in patients with comorbid bipolar disorder. | Narrow therapeutic window, high toxicity risk; requires strict monitoring of serum levels and renal/thyroid function; limited to specific cases with comorbid bipolar disorder where other treatments failed, not first-line. | |

| Atypical antipsychotics (aripiprazole, ziprasidone) | Modulates dopamine-serotonin system (partial agonism/antagonism). | Moderate efficacy in reducing self-injury in patients with psychotic symptoms, agitation or borderline traits. | Metabolic abnormality risks (weight gain, glucose/lipid disturbances), require long-term monitoring. | |

| Antidepressants (SSRIs like fluoxetine/sertraline, SNRIs like venlafaxine) | Modulates serotonin and/or norepinephrine levels. | May reduce self-injury in patients with comorbid depressive disorders. | Black box warning for children/adolescents, may increase suicide risk; require low starting dose and close monitoring. | |

| Combination therapy (e.g., neurofeedback + sertraline, or sertraline + olanzapine) | Neurofeedback enhances cognitive control, medication modulates neurochemistry, and potential synergistic effects. | May improve outcomes in treatment-resistant patients, but evidence needs strengthening. | Combination therapy (especially with olanzapine) significantly increases metabolic side effect risk, requires careful risk-benefit assessment and monitoring. | |