| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 17, Number 1, January 2025, pages 14-21

Predicting Extended Intensive Care Unit Stay Following Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting and Its Impact on Hospitalization and Mortality

Nizar R. Alwaqfia, b, d, Majd M. AlBarakata, c, Walid K. Hawashina, Hala R. Qarioutic, Ayah J. Alkrarhaa, Rana B. Altawalbeha

aFaculty of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

bDivision of Cardiovascular Surgery, Department of General Surgery, King Abdullah University Hospital, Irbid, Jordan

cDepartment of General Surgery, King Abdullah University Hospital, Irbid, Jordan

dCorresponding Author: Nizar R. Alwaqfi, Division of Cardiovascular Surgery, Department of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid 2210, Jordan

Manuscript submitted August 12, 2024, accepted December 11, 2024, published online December 31, 2024

Short title: ICU Stay Prediction After CABG

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6024

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is a prevalent surgical procedure aimed at alleviating symptoms and improving survival in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD). Postoperative care typically necessitates an intensive care unit (ICU) stay, which is ideally less than 24 h. However, various preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative factors can prolong ICU stays, adversely affecting hospital resources, patient outcomes, and overall healthcare costs. This study investigates the factors contributing to prolonged ICU stay (> 48 h) following CABG and CABG combined with valve surgery, and examines the associated impacts on complications and mortality.

Methods: This retrospective cohort study analyzed 1,395 patients who underwent isolated CABG or CABG combined with heart valve surgery at King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH) between January 2004 and December 2022. Patients were categorized into two groups: those with ICU stays ≤ 48 h (group 1, n = 1,082) and those with ICU stays > 48 h (group 2, n = 313). Clinical, laboratory, and demographic data were collected and evaluated to identify risk factors for prolonged ICU stays.

Results: Patients in group 2 were older, with a mean age of 61.5 years compared to 58.7 years in group 1 (P < 0.001). Significant predictors of prolonged ICU stay included preoperative conditions such as recent myocardial infarction (odds ratio (OR) = 1.69, P = 0.015), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma (OR = 1.49, P = 0.003), and preoperative renal impairment (OR = 1.89, P = 0.002). Intraoperative factors such as emergency or urgent procedures (OR = 2.19, P < 0.001) and prolonged ventilator support (OR = 5.92, P < 0.001) were also significant. Postoperative complications, including renal impairment (OR = 6.78, P < 0.001) and pneumonia or sepsis (OR = 8.92, P < 0.001), were strongly associated with extended ICU stays.

Conclusions: Prolonged ICU stays are indicative of patients with more severe baseline conditions, greater surgical complexity, and higher rates of postoperative complications, which collectively contribute to increased risks of severe adverse outcomes and mortality. Prolonged ICU stays after CABG are strongly associated with preoperative comorbidities, intraoperative challenges, and postoperative complications, leading to increased mortality and significant healthcare resource utilization. Identifying these risk factors and implementing targeted strategies to address them can help minimize ICU stay durations, improve patient outcomes, and enhance the efficiency of cardiac surgery care. Future research should focus on refining predictive models and optimizing perioperative management to further reduce the burden of prolonged ICU stays on healthcare systems.

Keywords: CABG; ICU; Hospitalization; Mortality

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is considered the number one cause of death around the world [1]. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is the most commonly performed type of cardiac surgery worldwide. CABG aims to improve the quality of life of patients by alleviating angina and heart failure (HF) symptoms and increasing survival rates [2]. Although CABG shows beneficial outcomes in managing CAD, postoperative monitoring mandates intensive care unit (ICU) stays after surgery [3]. After surgery, patients optimally stay less than 24 h, but factors such as patient profiles, perioperative and postoperative states, and operative events determine ICU-length of stay (LOS).

Prolonged ICU-LOS might be related to preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative factors including advanced age, reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (EF), chronic lung disease and inotropic agents administered in the immediate postoperative period [4, 5]. Postoperative complications such as surgical infections, stroke, arrhythmias, pneumonia, perioperative or postoperative myocardial infarction (MI), and pericarditis were related to prolonged ICU-LOS [6]. Due to limited ICU settings, prolonged ICU-LOS might delay elective CABG surgeries and elevate healthcare costs due to limited ICU resources. In addition, it limits ICU services for other critically ill patients.

In addition, prolonged ICU-LOS might be associated with postoperative complications and higher mortality rates [7]. On the other hand, preterm ICU patient discharge is associated with higher rates of readmission, leading to higher rates of mortality. Thus, determining the optimal discharge time will help reduce poor outcomes and maximize the operating process [8].

The duration of ICU stay after cardiac surgery is typically determined by a combination of clinical factors. These include the stability of vital signs, resolution of immediate postoperative complications, and the patient’s ability to meet extubation and mobilization criteria. Prolonged ICU stays often arise from underlying medical comorbidities, the complexity of the surgical procedure, and postoperative complications, such as infection or renal failure. Understanding these factors is critical to interpreting prolonged ICU stays as a marker of severity rather than a direct cause of adverse outcomes [7, 8].

In this study, factors contributing to prolonged ICU-LOS (more than 48 h) will be discussed based on patients that underwent CABG and CABG combined with valve surgery at King Abdullah University Hospital (KAUH), besides its relationship with some complications and mortality. This will help develop a more precise index predicting ICU-LOS and lowering its burden on the health care service.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and included patients

This retrospective cohort study included all patients who underwent isolated CABG at KAUH in Northern Jordan from January 2004 to December 2022. Patients who underwent repeat CABG procedures were excluded from the analysis. A total of 1,395 consecutive patients were included in this study. After surgery, patients are usually transferred to the cardiac ICU (CICU) on the ventilator. Patients were transferred to the floor after extubation, and they were able to ambulate, and no longer required inotropes and vasopressors. Usually, stable patients are transferred on the second postoperative day. In this study, patients were categorized into two groups: group 1 (normal ICU stay, less than 48 h, n = 1,082 patients) and group 2 (prolonged ICU stay, more than 48 h, n = 313 patients). Clinical, laboratory, and demographic data were obtained retrospectively from the patient’s medical records, including preoperative medication use. The medical records were reviewed for: prior stroke (results of brain computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), when available, or presence of unresolved neurological deficit), recent MI (elevation of cardiac enzymes or as evidenced by electrocardiogram (ECG) 4 weeks before surgery), HF (symptomatic patients or on anti-HF treatment), diabetes mellitus (DM, on oral hypoglycemic agents (OHAs) or insulin), hypertension (previously diagnosed and on anti-hypertensive treatment), chronic renal impairment (CRI, creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/dL or on chronic dialysis), peripheral vascular disease (PVD, positive history of intermittent claudication or a documented clinical evidence of peripheral ischemia), left ventricular EF (by either angiography or echocardiography), number of diseased coronary arteries (based on coronary angiogram and operative reports), emergency/urgent surgery (within 24 h from time of cardiac catheterization), prolonged inotropic support (continues for more than 48 h after surgery), and prolonged ventilation support (continues for more than 12 h). Pneumonia was diagnosed based on symptoms (cough, fever, and shortness of breath (SOB)), and radiological or microbiological evidence from sputum culture. Sternal wound infection was defined based on the presence of purulent discharge from the wound, positive wound culture, or radiological evidence of mediastinitis. Preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative measurements were evaluated as possible independent risk factors for prolonged ICU stay after CABG.

Perioperative antithrombotic treatment

Patients taking aspirin (100 mg) did not have it discontinued preoperatively. Clopidogrel was discontinued 5 days before elective surgery. Heparin (3.0 mg/kg) was administered intravenously before the completion of internal thoracic artery harvesting to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) of more than 400 s, and it was neutralized at the end of the procedure by protamine sulfate (3.0 mg/kg). Further protamine was given if ACT was > 140 s before chest closure. Neither aprotinin nor tranexamic acid was used in any of the patients. Packed red blood cells (PRBCs), fresh frozen plasma (FFP), and platelets were transfused according to the amount of bleeding, international normalized ratio (INR) levels, and platelet counts. Clopidogrel was used postoperatively in patients with recent percutaneous coronary intervention and in those with small diffusely diseased coronaries decided by the operating surgeon, as well as patients who developed CVA. Enoxaparin (40 mg once daily) was started, if no contraindication, in all patients on the next morning of the day of surgery. For patients with combined valve surgery, warfarin (Coumadin) was started on the second postoperative day.

Intraoperative data

Assessment of the ascending aorta was performed by digital palpation. Standard techniques were used for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). Perfusion was maintained at 2.0 to 2.4 L/min/m2, and systemic perfusion pressure was kept at 60 - 80 mm Hg. Myocardial viability was preserved with cold antegrade potassium cardioplegia and topical hypothermia. Body temperature was maintained between 28 and 32 °C. CPB time was considered prolonged if > 120 min, and cross-clamp time was considered prolonged if > 90 min.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range), depending on whether the data followed a normal distribution. Categorical variables are displayed as frequencies and percentages. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to compare categorical data without adjusting for covariates. Statistical significance was determined with a P value threshold of less than 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using Python (version 3.9, Python Software Foundation).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jordan University of Science and Technology approved the study with the number 519 of the year 2023. Consent forms were obtained from the patients before participation. The study followed the ethical principles outlined in the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki for medical research on humans.

| Results | ▴Top |

Social and clinical characteristics of included patients

The study included a total of 1,395 patients, who were divided into two groups based on their ICU stay duration: group 1 (ICU stay > 2 days, n = 313 patients), and group 2 (ICU stay ≤ 2 days, n = 1,082 patients).

The average age of patients in group 1 was significantly higher (61.5 years) compared to group 2 (58.7 years), with a P value < 0.001. Additionally, a higher percentage of patients aged ≥ 70 years were in group 1 (22.7%) compared to group 2 (14.0%) (P < 0.001). The distribution of male patients was similar between both groups (79.6% in group 1 vs. 76.9% in group 2, P = 0.321). The mean body mass index (BMI) in group 1 (26.7) compared to group 2 (26.3) was not statistically significant (P = 0.158) (Table 1).

Click to view | Table 1. Characteristics of Included Patients |

A comprehensive overview of the medical history of the studied patients is presented in Table 2. Statistically significant differences were observed in several conditions. Patients with a recent MI (30% in group 1) were significantly more likely to have extended ICU stays, compared to patients (17.6%) in group 2 (P value < 0.001). Similarly, a higher prevalence of smoking was noted among patients in group 1 (63.6% vs. 55.2%, P value = 0.008). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma was also more prevalent in group 1 (17.6% vs. 11.2%, P value = 0.003). Preoperative CRI showed a significant association with extended ICU stays (11.2% vs. 6.1%, P value = 0.002). Conversely, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, DM, family history of CAD, history of central nervous system disease (such as stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA)), New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III/IV heart failure, history of PVD, use of clopidogrel, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and statins did not show significant differences between the two groups. Notably, preoperative atrial fibrillation (AF) was significantly more common in group 1 as compared to group 2 (8.6% vs. 3.7%, P value < 0.001). These findings underscore the importance of certain comorbidities in predicting prolonged ICU stays.

Click to view | Table 2. Medical History of Included Patients |

Predictors of prolonged ICU stays

The analysis identified several significant predictors of prolonged ICU stays. Mitral regurgitation (MR) grade 1-2 (OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.83 - 1.46, P = 0.492) and left main (LM) coronary artery stenosis ≥ 70% (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.47 - 1.07, P = 0.11) were not significantly associated with prolonged ICU stays. EF > 50% (OR = 1.17, 95% CI: 0.90 - 1.52, P = 0.227) and EF 40-49% (OR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.68 - 1.26, P = 0.656) also did not show significant associations. However, EF 30-39% (OR = 0.53, 95% CI: 0.33 - 0.84, P = 0.008) was significantly associated with a reduced risk of prolonged ICU stays, whereas EF < 30% (OR = 1.85, 95% CI: 0.81 - 4.20, P = 0.139) did not reach statistical significance.

Preoperative coronary stents (OR = 1.69, 95% CI: 1.10 - 2.57, P = 0.015) and exploration for postoperative bleeding (OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.08 - 2.77, P = 0.022) were significant predictors of prolonged ICU stays. Emergency or urgent procedures (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.60 - 3.00, P < 0.001) and prolonged ventilator support (OR = 5.92, 95% CI: 3.79 - 9.23, P < 0.001) were highly significant predictors. Postoperative renal impairment (OR = 6.78, 95% CI: 4.48 - 10.26, P < 0.001) and pneumonia/sepsis (OR = 8.91, 95% CI: 4.48 - 16.00, P < 0.001) also showed strong associations with prolonged ICU stays.

Age (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01 - 1.04, P < 0.001) and intraoperative blood transfusion (OR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.22 - 2.03, P < 0.001) were significant predictors, whereas BMI (OR = 1.01, 95% CI: 0.99 - 1.04, P = 0.161) did not show a significant association. The need for preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) (OR = 2.49, 95% CI: 0.78 - 7.91, P = 0.121) and aorta cross-clamp time > 90 min (OR = 0.91, 95% CI: 0.57 - 1.46, P = 0.712) were not significant predictors. CPB time > 120 min (OR = 0.98, 95% CI: 0.72 - 1.34, P = 0.92) also did not show a significant association (Table 3.)

Click to view | Table 3. Risk Factors for Prolonged ICU Stay |

Effect of prolonged ICU stay on risk for other complications, mortality and hospital stay

The impact of prolonged ICU stay on postoperative complications is outlined in Table 4. The analysis revealed that prolonged ICU stay significantly increases the risk of postoperative stroke or TIA, with an OR of 3.27 (95% CI: 1.48 - 7.25, P = 0.003), similarly regarding the new onset of pneumonia or sepsis, with OR of 8.91 (95% CI: 4.96 - 16.00, P < 0.001). Additionally, the odds of mortality were notably higher in patients with extended ICU stay, reflected by an OR of 3.08 (95% CI: 1.96 - 4.86, P < 0.001). However, the incidence of sternal infections did not differ significantly between patients with prolonged ICU stays and those without, with an OR of 1.00 (95% CI: 0.68 - 1.47, P = 0.987). These findings highlight the critical need for strategies to reduce ICU duration to mitigate the risk of severe postoperative complications and mortality.

Click to view | Table 4. Effect of Prolonged ICU Stay on Complications |

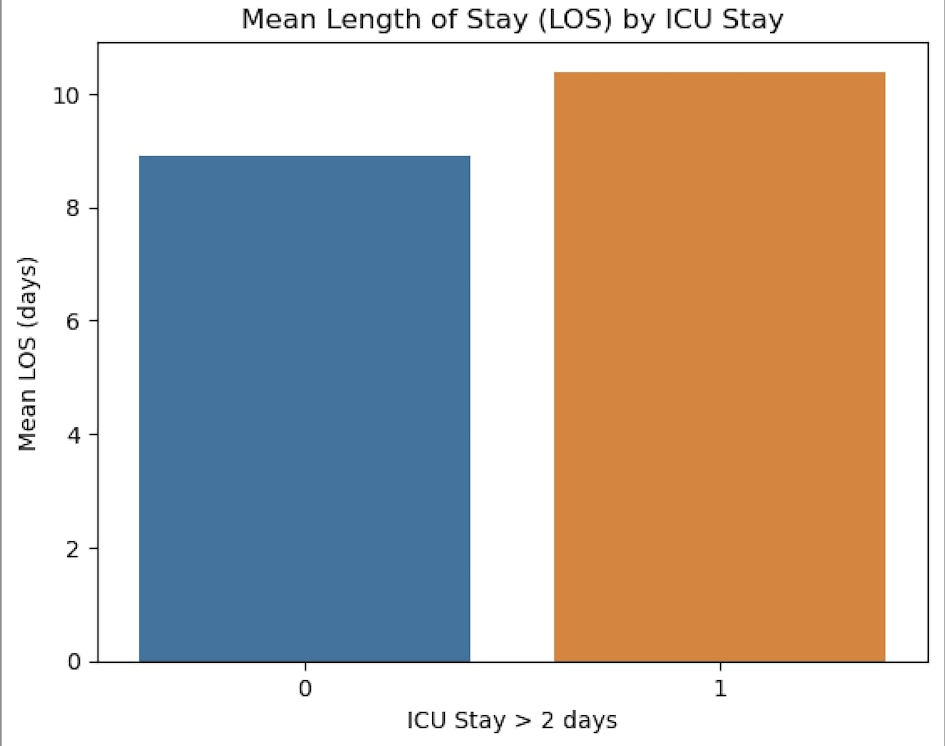

An independent sample t-test was conducted to compare LOS in the hospital for patients with ICU stays greater than 2 days and those with ICU stays of 2 days or less. There was a significant difference in the LOS for patients with ICU stays greater than 2 days (mean = 10.4 days, SD = 3.2) compared to those with ICU stays of 2 days or less (mean = 8.9 days, SD = 2.5); t (1,393) = 3.76, P = 0.000175 (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. The mean length of hospital stays in the two groups. ICU: intensive care unit. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study, 313 patients experienced prolonged ICU stay. We analyzed preoperative, operative, and postoperative variables to identify predictors of extended LOS. Several factors did not show a significant correlation with prolonged ICU stay. These included MR grade 1-2, EF > 50%, EF 40-49%, EF < 30%, and LM coronary artery stenosis ≥ 70%. Additionally, BMI, CPB time > 120 min, the need for preoperative IABP, and aortic cross-clamp time > 90 min were not significantly associated with extended ICU stay.

Conversely, several factors were identified as significant predictors of prolonged ICU stay. These included age, EF 30-39%, presence of preoperative coronary arteries stents, emergency or urgent surgery, intraoperative blood transfusion, exploration for postoperative bleeding, prolonged ventilator support, postoperative renal impairment, and postoperative pneumonia/sepsis.

The correlations between age and intraoperative blood transfusion with prolonged ICU stay were consistent with previous studies. Michalopoulos et al [5] cited several studies supporting the contribution of age to longer LOS. They also analyzed a non-monotonic relationship between longer LOS and patients receiving more than six blood units. In contrast, Ibrahim et al [9] concluded differently regarding blood transfusions and found that age was not a significant predictor of prolonged LOS, likely due to their younger patient cohort.

Preoperative coronary arteries stents, prolonged ventilator support, postoperative renal impairment, and pneumonia/sepsis were highly significant predictors of prolonged ICU stay. The study of Ibrahim et al [9] confirmed these factors in their initial univariate analysis. Prolonged ventilator support (> 12 h) may indicate poor preoperative lung function or complications during or after surgery. Pneumonia, the most common infection following cardiac surgery, strongly predicted prolonged LOS and often necessitated reintubation.

Left ventricular EF generally did not reach statistical significance, though EF 30-39% was significantly associated with a reduced risk of prolonged ICU stay. Michalopoulos et al [5] suggested that left ventricular EF indirectly affects LOS, as patients with low EF may require blood transfusions or inotropes. However, they also noted that revascularization can enhance EF, potentially shortening ICU-LOS, which aligns with our findings.

Postoperative acute kidney injury (AKI) was a significant predictor of prolonged ICU stay in several studies, especially in patients who had experienced MI within 90 days before CABG surgery. In our study CPB time > 120 min and aortic cross-clamp time > 90 min were not significantly associated with prolonged ICU stay, consistent with the findings of Michalopoulos et al [5] and Ibrahim et al [9], who noted considerable OR for these variables before further analysis.

Other suggested predictors not analyzed in this study but mentioned in others include postoperative AF, atelectasis, the insertion of more than two chest tubes, and the number of inotropes used within 6 h after surgery. Michalopoulos et al [5] noted that patients receiving more than two inotropes often experienced prolonged LOS due to low cardiac output syndrome, respiratory failure, and neuropsychiatric states, whereas those receiving fewer than two inotropes mainly faced hypoxia and AF.

Postoperative AF was found to be an independent predictor of prolonged LOS in other studies [5, 9, 10]. It typically occurs around day 2 post-CABG and significantly extends ICU stay. Patients not on beta-blocker drugs had longer ICU-LOS, possibly due to beta-blockers’ protective effects against postoperative AF or the absence of protocol doses in urgent surgeries, which indirectly aligns with our study results.

The number of chest tubes inserted during CABG surgeries was a predictor of increased ICU-LOS, as suggested by Zarrizi et al [10]. Insertion of more than two chest tubes and persistent pleural effusions due to internal mammary artery usage predict ongoing pulmonary complications and the need for extended ICU stays. Zarrizi et al [10] excluded valvular replacement surgeries from their analysis, highlighting the inevitable pulmonary complications, mainly atelectasis, resulting from prolonged CPB usage and pulmonary shutdown. Late atelectasis and sternal wound recovery may lead to superficial breathing, prolonged complications, and longer LOS. Although not explicitly stated as a predictor, Zarrizi et al [10] suggested that older age might influence these events.

Potential limitations of the analyzed studies include the early discharge of patients to manage other patients awaiting surgery, as noted by Zarrizi et al [10] and Michalopoulos et al [5] pointed out that data collected after patients stayed in the ICU for more than 6 h might limit the use of data as preoperative indicators. Hospital policies might also affect LOS, with patients in stable post-surgical conditions being discharged earlier to reduce waiting times and ICU-LOS.

The present study revealed that a prolonged ICU stay is significantly associated with an increase in postoperative complications, such as postoperative stroke or TIA. This finding aligns with several studies. For instance, one study [11] reported that ICU stays of 3 - 14 days are associated with a higher incidence of stroke (2%), compared to stays of less than 2 days (0.7%), with an OR of 9.13 (95% CI: 5.14 - 16.23, P < 0.0001). Additionally, mortality rates were 8% in patients with prolonged ICU stays, compared to 2% in those with shorter stays. However, unlike our study, which found no difference in infection rates between the two groups, Silberman et al [11] (2013) reported a higher infection rate (21%) in patients with prolonged ICU stays compared to those with stays of less than 2 days (7%). This association raises important questions about causality: whether prolonged stays result in higher infection rates or whether patients with pre-existing infections or other complications are more likely to require extended ICU care. While ICU hygiene and preventive measures are designed to minimize nosocomial infections, the interplay of pre-existing conditions, procedural complexity, and postoperative management likely drives these differences. Our findings support the notion that prolonged ICU stays are a marker of severity rather than a causal factor in adverse outcomes [11]. The association between prolonged ICU stay and sepsis underscores the importance of robust infection control measures. Strengthening ICU hygiene practices could significantly reduce nosocomial infection rates.

Another study [12], consistent with our findings, found that subjects who spent two or more nights in intensive care had a higher incidence of minor complications (66% vs. 43%, P < 0.001). This group also experienced a significant increase in all serious complications, underwent more frequent surgeries due to heavy bleeding (15% vs. 3%, P < 0.001), and had a seven-fold higher 30-day mortality rate compared to the control group (7% vs. 1%, P < 0.001). Similarly, another study [13] conducted in a major hospital in Oman reported that a higher number of patients with prolonged ICU stay experienced postoperative complications, affecting at least half of the patients. A prospective cohort study [14] that agrees with our study showed that major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events (P < 0.01), 30-day mortality (P < 0.01), and length of ward stay (P < 0.01) were all higher with prolonged ICU stay. It is noteworthy to say that ICU decisions, including ventilator duration and LOS, are influenced by both standardized protocols and individual clinical judgment. Consistent application of evidence-based protocols could reduce variability in care and improve patient outcomes.

It is important to recognize that the observed associations do not suggest that prolonged ICU stay itself causes poor outcomes. Instead, these outcomes are likely a consequence of the same factors, such as preoperative comorbidities, intraoperative complexity, or postoperative complications, which also extend ICU stays. Future studies should focus on delineating these relationships to better understand how early interventions can mitigate risks and optimize ICU resource utilization.

Conclusions

Prolonged ICU stays following CABG are largely driven by preoperative comorbidities and intraoperative events. These prolonged stays are linked to a heightened risk of severe postoperative complications and increased mortality. By identifying and addressing these risk factors through optimized surgical and postoperative care protocols, ICU durations can be better understood and managed. However, it is important to recognize that prolonged ICU stays are often a reflection of patient severity and complexity rather than a direct cause of adverse outcomes. Future studies should incorporate prospective designs to evaluate causal pathways and refine predictive models that integrate clinical decision-making processes.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

We received no funding for this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Consent forms were obtained.

Author Contributions

NA and MMA contributed to the idea validation and methodology development. HRQ was responsible for data collection. NA supervised the project, while MMA conducted the data analysis. AJA and WKH contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; AF: atrial fibrillation; AKI: acute kidney injury; BMI: body mass index; CABG: coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD: coronary artery disease; CI: confidence interval; CICU: cardiac intensive care unit; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPB: cardiopulmonary bypass; CRI: chronic renal impairment; CT: computed tomography; DM: diabetes mellitus; EF: ejection fraction; FFP: fresh frozen plasma; HF: heart failure; ICU: intensive care unit; IABP: intra-aortic balloon pump; INR: international normalized ratio; KAUH: King Abdullah University Hospital; LM: left main (coronary artery); LOS: length of stay; MI: myocardial infarction; MR: mitral regurgitation; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NYHA: New York Heart Association; OHAs: oral hypoglycemic agents; OR: odds ratio; PVD: peripheral vascular disease; TIA: transient ischemic attack

| References | ▴Top |

- Shahjehan RD, Sharma S, Bhutta BS. Coronary Artery Disease. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL). 2024.

pubmed - Velazquez EJ, Lee KL, Jones RH, Al-Khalidi HR, Hill JA, Panza JA, Michler RE, et al. Coronary-artery bypass surgery in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1511-1520.

doi pubmed - Pimentel MF, Soares MJF, Murad JAJ, Oliveira MAB, Faria FL, Faveri VZ, Iano Y, et al. Predictive factors of long-term stay in the ICU after cardiac surgery: logistic CASUS score, serum bilirubin dosage and extracorporeal circulation time. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;32(5):367-371.

doi pubmed - Hein OV, Birnbaum J, Wernecke K, England M, Konertz W, Spies C. Prolonged intensive care unit stay in cardiac surgery: risk factors and long-term-survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81(3):880-885.

doi pubmed - Michalopoulos A, Tzelepis G, Pavlides G, Kriaras J, Dafni U, Geroulanos S. Determinants of duration of ICU stay after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77(2):208-212.

doi pubmed - Gunnarsdottir SLX, Gunnarsdottir ELT, Heimisdottir AA, Heidarsdottir SR, Helgadottir S, Sigurdsson MI, Guethbjartsson T. [The use of intra aortic balloon pump in coronary artery bypass graft surgery]. Laeknabladid. 2020;106(2):63-70.

doi pubmed - Almashrafi A, Elmontsri M, Aylin P. Systematic review of factors influencing length of stay in ICU after adult cardiac surgery. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:318.

doi pubmed - Wagener G, Minhaz M, Wang S, Panzer O, Wunsch H, Playford HR, Sladen RN. The Surgical Procedure Assessment (SPA) score predicts intensive care unit length of stay after cardiac surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(2):443-450.

doi pubmed - Ibrahim KS, Kheirallah KA, Al Manasra ARA, Megdadi MA. Factors affecting duration of stay in the intensive care unit after coronary artery bypass surgery and its impact on in-hospital mortality: a retrospective study. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2024;19(1):45.

doi pubmed - Zarrizi M, Paryad E, Khanghah AG, Leili EK, Faghani H. Predictors of length of stay in intensive care unit after coronary artery bypass grafting: development a risk scoring system. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;36(1):57-63.

doi pubmed - Silberman S, Bitran D, Fink D, Tauber R, Merin O. Very prolonged stay in the intensive care unit after cardiac operations: early results and late survival. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96(1):15-21; discussion 21-12.

doi pubmed - Yesiler FI, Akmatov N, Nurumbetova O, Beyazpinar DS, Sahinturk H, Gedik E, Zeyneloglu P. Incidence of and risk factors for prolonged intensive care unit stay after open heart surgery among elderly patients. Cureus. 2022;14(11):e31602.

doi pubmed - Almashrafi A, Alsabti H, Mukaddirov M, Balan B, Aylin P. Factors associated with prolonged length of stay following cardiac surgery in a major referral hospital in Oman: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010764.

doi pubmed - Diab MS, Bilkhu R, Soppa G, Edsell M, Fletcher N, Heiberg J, Royse C, et al. The influence of prolonged intensive care stay on quality of life, recovery, and clinical outcomes following cardiac surgery: A prospective cohort study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156(5):1906-1915.e3.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.