| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Review

Volume 000, Number 000, June 2025, pages 000-000

Oral Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Antagonists in the Treatment of Endometriosis: Advances in Research

Jing Yi Wanga, Yan Zhangb, d, Jin Dingc, d

aWannan Medical College, Wuhu 241000, Anhui, China

bDepartment of Gynecology, Seventeen Metallurgical Hospital of Ma’anshan City, Ma’anshan 243000, Anhui, China

cDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu, China

dCorresponding Author: Jin Ding, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, Nanjing 210009, Jiangsu, China; Yan Zhang, Department of Gynecology, Seventeen Metallurgical Hospital of Ma’anshan City, Ma’anshan 243000, Anhui, China

Manuscript submitted March 15, 2025, accepted May 23, 2025, published online June 16, 2025

Short title: Oral GnRH Antagonists in Treating Endometriosis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6236

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Non-peptide gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonists exhibit remarkable potency and specificity in inhibiting GnRH receptor activity. The orally administered versions of these drugs, notably elagolix and relugolix, have obtained official clearance in various countries for treating moderate-to-severe endometriosis-related pain. Concurrently, linzagolix and opigolix (ASP1707) continue to advance through late-stage clinical trials. The primary objective of this review is to comprehensively evaluate the clinical efficacy and safety profile of oral GnRH antagonists, specifically elagolix, relugolix, linzagolix, and opigolix, for the management of endometriosis-associated pain. Specifically, this study summarizes and analyzes their effectiveness in alleviating dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain, evaluates the dose-dependent impacts on bone mineral density and adverse effects such as hot flushes, and explores the role of add-back therapy in improving treatment safety and patient adherence. Research has demonstrated that oral GnRH antagonists effectively alleviate endometriosis-related pain while enhancing patients’ quality of life. Furthermore, when combined with add-back therapy, these medications enhance treatment safety and contribute to greater patient compliance. Compared to alternative hormonal treatments, oral GnRH antagonists emerge as a particularly promising approach for managing endometriosis.

Keywords: Endometriosis; Pharmacological treatment; Non-peptide GnRH receptor antagonists; Add-back therapy

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Endometriosis is a chronic inflammatory disease driven by estrogen, where tissue similar to the endometrium forms in areas outside the uterus [1]. Its primary clinical manifestations including chronic non-menstrual pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, infertility, and dyspareunia can detrimentally affect both physical and mental well-being, ultimately disrupting intimate relationships and daily routines [2, 3]. Studies have shown that pelvic endometriosis is prevalent in an estimated 6% to 10% of women of reproductive age, with chronic pelvic pain and infertility affecting approximately 35% to 50% of diagnosed cases [4]. The onset of endometriosis may be related to retrograde menstruation, abnormal hypomethylation in the estrogen receptor β promoter region, and estrogen-driven inflammation, which may be a core pathological process of the disease [5]. Therefore, reducing circulating estrogen levels is an effective treatment approach [6, 7]. The management of endometriosis encompasses both pharmacological and surgical interventions, primarily focused on symptom relief and lesion control. While surgical intervention can remove visible endometriotic lesions, it remains an incomplete solution, as the condition may persist or recur. Lesions missed during surgical intervention may continue to develop under the influence of circulating estrogen, which contributes to a high rate of recurrence following surgery [8]. First-line treatment strategies for alleviating endometriosis-associated pain (EAP) often include the administration of combined oral contraceptives (COCs) or progestins [9]. However, due to progesterone resistance, these treatments demonstrate efficacy in only about two-thirds of patients suffering from endometriosis-related pain [10-13]. For women who are resistant to progestins, second-line treatments include GnRH agonists, such as long-acting injectable formulations, and aromatase inhibitors [14]. At present, aromatase inhibitors are primarily prescribed for individuals with endometriosis-related pain that remains refractory to conventional therapies. In contrast, GnRH agonists quickly attach to GnRH receptors, provoking a surge in follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion that results in a marked release of estrogen, a phenomenon commonly referred to as the “flare effect.” High levels of estrogen result in the downregulation of pituitary GnRH receptors, thereby suppressing the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, reducing endogenous GnRH secretion, and ultimately lowering circulating estrogen levels; this effect is not dose-dependent [15]. Prolonged use of GnRH agonists can lead to estrogen depletion-related side effects; therefore, for treatments exceeding 6 months, add-back therapy (ABT) with estradiol and norethindrone acetate is recommended to mitigate these effects [6]. The advent of GnRH antagonists has expanded the treatment options for endometriosis and can be used with or without ABT [16]. GnRH antagonists are generally divided into peptide-based and non-peptide variants. Studies suggest that these compounds hold significant potential in enhancing endometriosis treatment [17]. Accordingly, the present review sets out to synthesize and critically appraise the accumulated clinical evidence on the four oral, non-peptide GnRH receptor antagonists that have advanced furthest in development, i.e., elagolix, relugolix, linzagolix, and opigolix. By providing an integrated assessment of both therapeutic benefit and risk, we aim to inform rational, patient-centered selection of oral GnRH antagonists in contemporary endometriosis management.

| Methods | ▴Top |

A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library to identify clinical and preclinical studies evaluating oral GnRH antagonists in endometriosis. The search period covered all articles published up to February 2025. The following search terms and Boolean operators were applied: (“endometriosis” OR “endometrioma” OR “deep infiltrating endometriosis” OR “DIE”) AND (“oral GnRH antagonist” OR “elagolix” OR “relugolix” OR “linzagolix” OR “opigolix” OR “ASP1707”). Reference lists of relevant reviews and included studies were also manually screened to capture additional eligible publications. Studies were included if they 1) investigated the efficacy, safety, or pharmacology of oral GnRH antagonists for the management of EAP, 2) reported clinical outcomes, pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic data, or quality-of-life results, and 3) were published in English. Both randomized controlled trials and observational studies, as well as relevant animal studies, were considered. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility, followed by full-text review. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Risk of bias (RoB) for each randomized study was independently evaluated by two reviewers using the Cochrane Collaboration tool (Handbook v5.1.0), with disagreements resolved by discussion and final judgements summarized in a tabulated figure. Certainty of evidence was evaluated according to the GRADE framework.

| Results | ▴Top |

Non-peptide GnRH antagonists mechanism of action

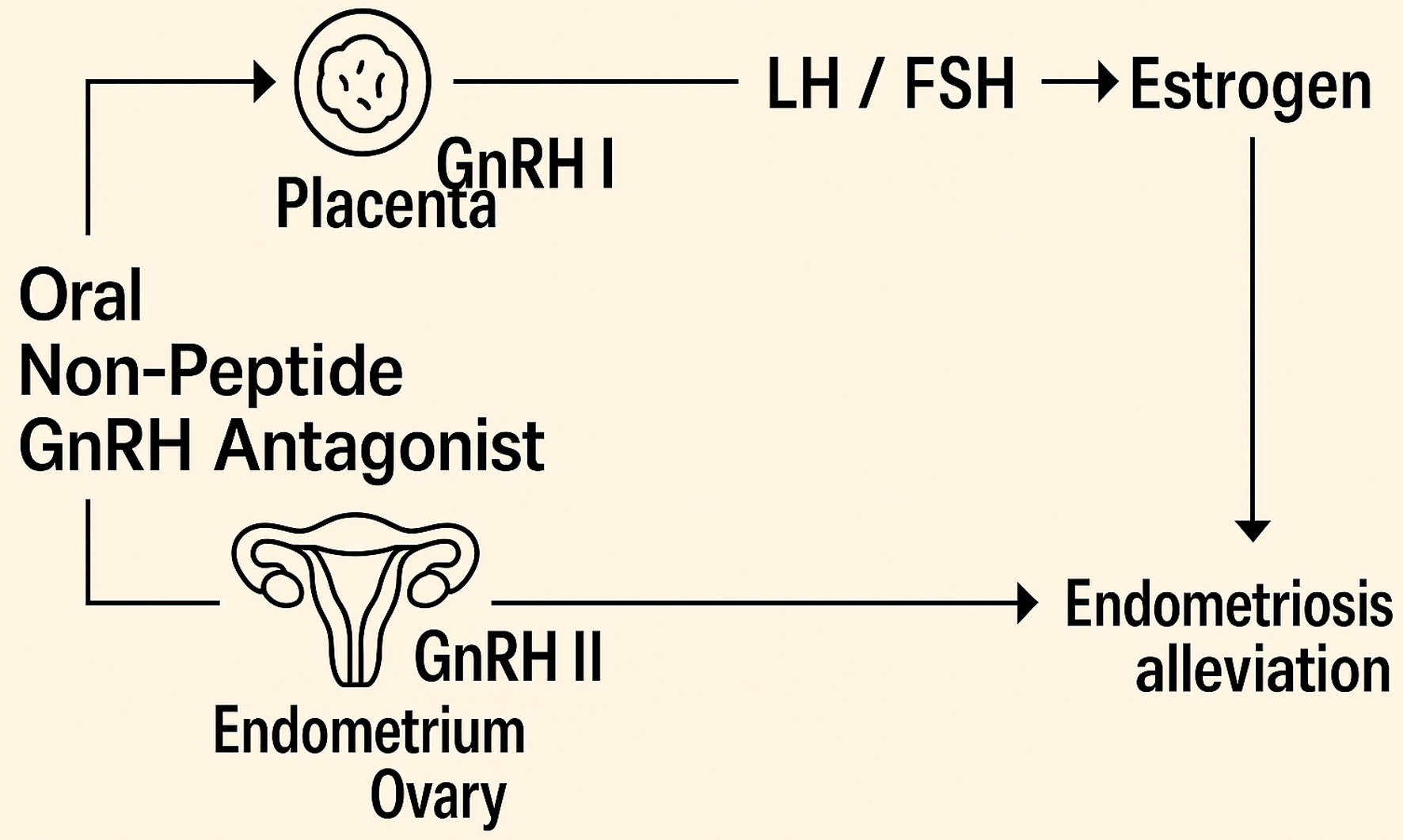

GnRH in the human body is classified into two types: GnRH I, which acts on the pituitary gland, and GnRH II, which appears in other areas of the brain and peripheral tissues [18]. GnRH I interacts with pituitary cell receptors, stimulating the release of LH and FSH. In contrast, GnRH antagonists competitively occupy these receptors and rapidly suppress the HPO axis, thereby inhibiting the secretion of LH and FSH and leading to decreased estrogen levels. Owing to their direct antagonistic mechanism, GnRH antagonists avoid triggering the so-called “flare effect” [19]. GnRH antagonists suppress estrogen production in a dose-dependent fashion, where lower doses lead to partial inhibition and higher doses result in almost complete suppression [17]. GnRH II exhibits significant expression in the placenta, endometrial tissues, and ovarian granulosa cells [18]. In patients with endometriosis, the inhibitory action mediated by endogenous GnRH II is impaired, leading to stronger proliferation of the endometrium [20]. GnRH antagonists also block GnRH II, suggesting that the inhibition of endometriosis by GnRH antagonists may also be related to this [21] (Fig. 1). The non-peptide structure of non-peptide GnRH antagonists prevents gastrointestinal protein hydrolysis, allowing them to be taken orally [17, 22].

Click for large image | Figure 1. Mechanism of action of oral GnRH antagonists. GnRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone. |

Pharmacokinetics

Drug interactions

Elagolix, relugolix, and opigolix are primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 (cytochrome P450 3A4 enzyme), so they should not be co-administered with CYP3A inhibitors or inducers, as these interactions could reduce therapeutic effects or increase the occurrence of adverse reactions [23, 24]. For elagolix, inhibitors of organic anion-transporting polypeptide 1B1 (OATP1B1) can increase its blood concentration, so co-administration is not recommended. Similarly, the blood concentration of relugolix may increase due to the effects of P-glycoprotein (P-gp) inhibitors, and co-administration should be avoided. Linzagolix is primarily metabolized by CYP2C8 and CYP2C9 and does not interact with CYP3A-related drugs. However, it should be avoided in combination with drugs that are substrates of CYP2C8 with a narrow therapeutic window [25].

Major pharmacodynamic differences

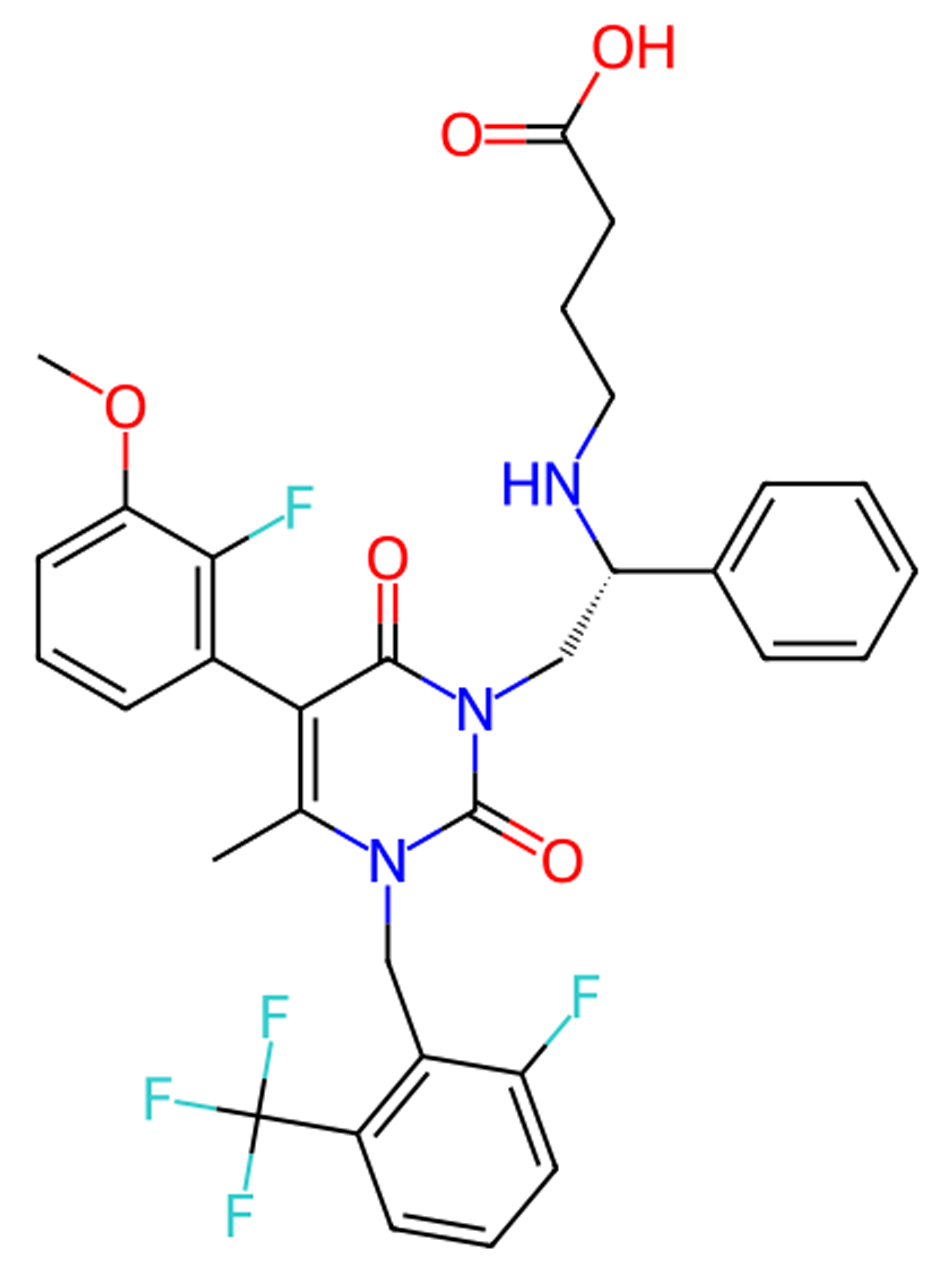

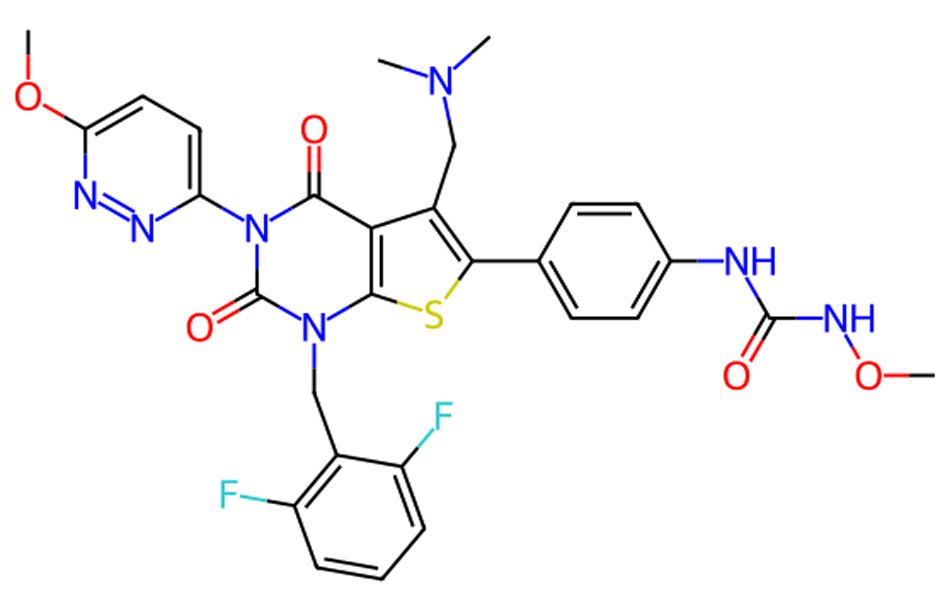

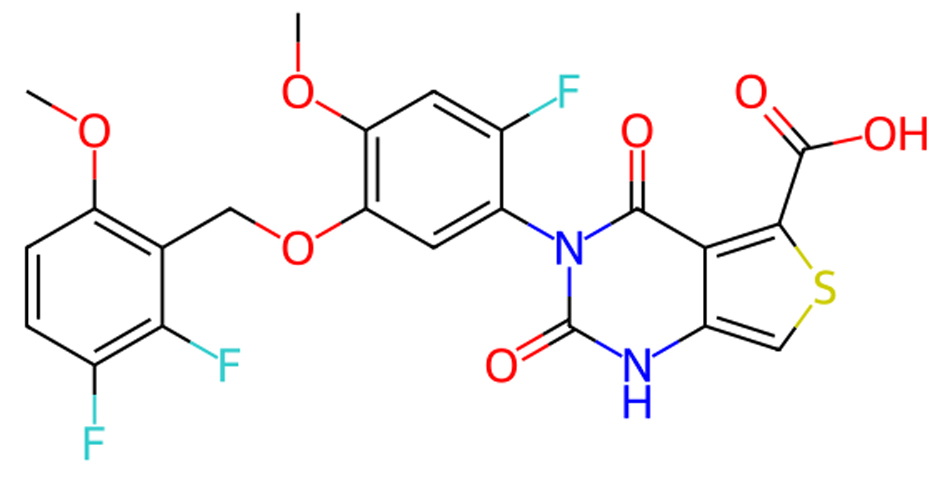

Marked pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic heterogeneity exists among the three marketed oral, non-peptide GnRH antagonists, and these differences largely dictate their dose regimens and monitoring requirements. Elagolix is absorbed fastest (Tmax of approximately 1 h) and has the shortest elimination half-life (4 - 6 h), with systemic exposure falling by up to 24% (area under the curve (AUC)) and 36% (Cmax) when taken with a high-fat meal (Fig. 2) [26]. Its extensive apparent distribution volume (881 - 1,674 L) and moderate plasma protein binding (approximately 80%) contrast with rapid oral clearance (123 - 144 L/h). Consequently, higher symptom control requires a twice-daily 200 mg schedule, whereas a once-daily 150 mg dose suppresses median estradiol to approximately 42 pg/mL but allows ovulation in approximately 50% of cycles, reflecting partial HPO axis inhibition. Relugolix shows low absolute bioavailability (approximately 12%), a later Tmax (approximately 2.3 h) and much longer effective and terminal half-lives (25 h and 60.8 h, respectively) (Fig. 3) [27]. Protein binding is 68-71%, and total clearance averages 26.4 L/h. Steady-state exposure after 120 mg once daily (AUC of approximately 407 ng h/mL) supports convenient single-tablet administration; however, repeat dosing produces a greater-than-proportional rise in Cmax, implying saturable first-pass loss. Linzagolix, although highly protein-bound (> 99%), distributes minimally (Vd of approximately 11 L), is absorbed within 2 h, and has an intermediate half-life (approximately 15 h) (Fig. 4) [28]. Apparent clearance after multiple 100 - 200 mg doses is only 0.5 L/h, yielding estradiol plateaus of 20 - 60 pg/mL and progesterone ≤ 3.1 ng/mL in up to 83% of women, levels that satisfy the “estradiol-threshold” for symptom control while limiting hypo-estrogenic toxicity. For opigolix (ASP1707) only sparse phase II data are available: steady-state pre-dose concentrations ranged from 0.53 to 3.85 ng/mL after 3 - 15 mg once daily, and no full pharmacokinetic profile has been published since development was halted in 2018 (Fig. 5) [29]. Taken together, elagolix’s short half-life necessitates bid dosing at higher exposures; relugolix and linzagolix support once-daily schedules owing to slower systemic clearance; and all three agents achieve partial, dose-dependent estradiol suppression, but differ in meal sensitivity, protein binding, and distribution, factors that must be weighed when tailoring therapy and planning ABT.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Molecular structure of elagolix. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Molecular structure of relugolix. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Molecular structure of linzagolix. |

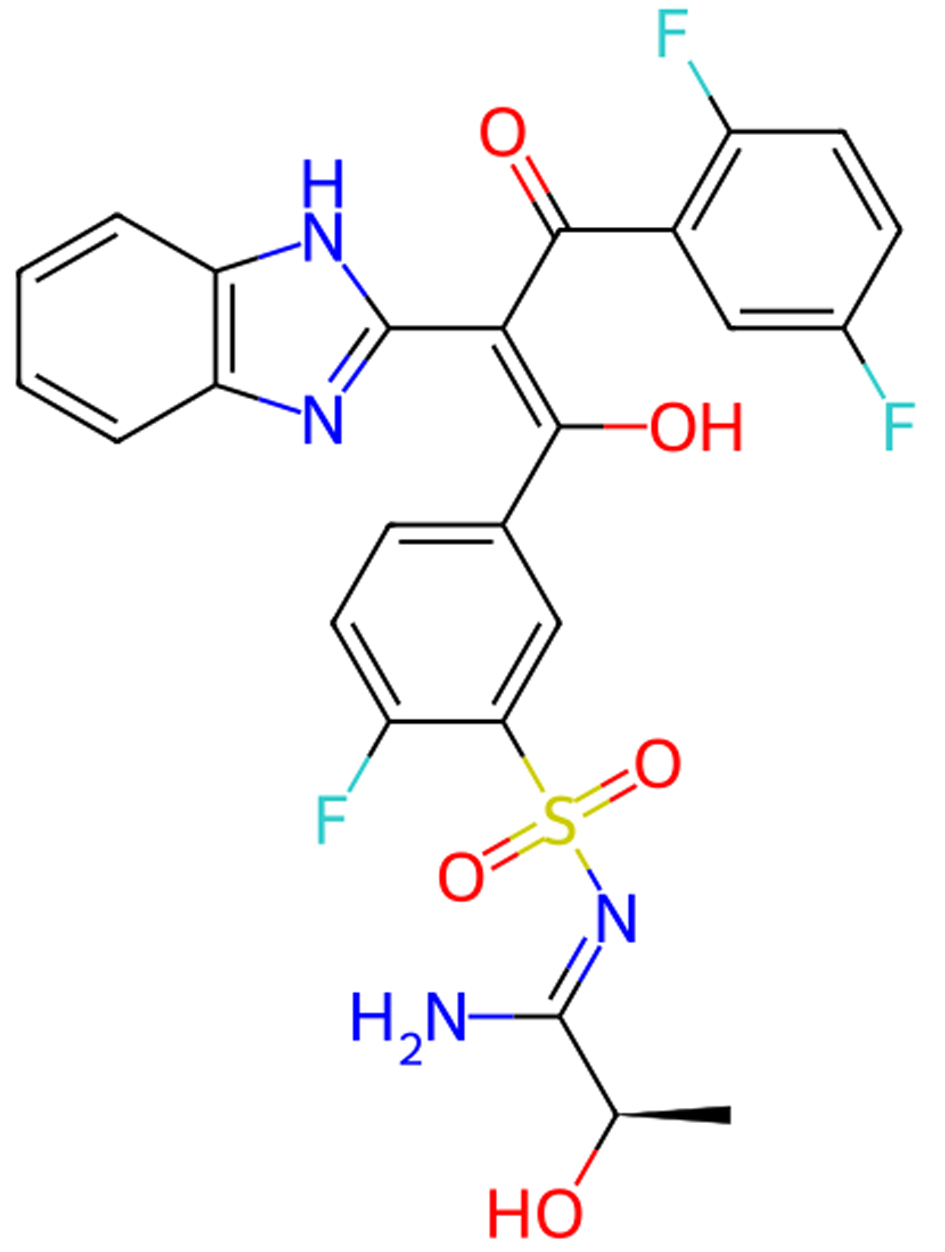

Click for large image | Figure 5. Molecular structure of opigolix. |

Dosage and administration

1) Elagolix (Orilissa®, AbbVie)

Elagolix received regulatory approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2018 for the management of moderate-to-severe endometriosis-related pain; Health Canada issued a parallel authorization later the same year [30, 31]. Elagolix is available in 150 and 200 mg tablet forms and is prescribed for the treatment of moderate-to-severe endometriosis-related pain. As per FDA guidelines, the recommended duration of therapy depends on the dosage: a daily 150 mg regimen should not exceed 2 years, while a 200 mg twice-daily regimen is limited to 6 months.

2) Relugolix (Myfembree®/Ryeqo®, Myovant Sciences-Sumitomo Pharma in partnership with Pfizer; Orgovyx®, Myovant Sciences-Sumitomo Pharma)

In 2022, the FDA granted approval for a once-daily, fixed-dose combination tablet containing 40 mg of relugolix, 1 mg of estradiol, and 0.5 mg of norethindrone acetate (marketed as Myfembree®) for a 1-year treatment course to manage moderate-to-severe endometriosis-related pain in premenopausal women. Earlier approvals include Orgovyx® (120 mg once daily) for advanced prostate cancer in the United States in 2020 and Myfembree® for heavy menstrual bleeding due to uterine fibroids in 2021 [32, 33]. In the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom, the identical combination tablet is marketed as Ryeqo®, first authorized in 2021 for fibroid-associated symptoms and extended in 2023 - 2024 to cover EAP [34, 35].

3) Linzagolix (Yselty®, Theramex under license from Kissei Pharmaceutical)

Linzagolix is still under clinical trial for its use in endometriosis, with a proposed dosage of 75 - 125 mg daily to balance pain relief and bone mineral density (BMD) goals [36]; however, the agent secured European Commission marketing authorization in June 2022 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe uterine fibroid symptoms and, in January 2025, for EAP [37, 38]. The product is not yet approved in the United States, but commercial launches have begun across several EU member states, led by Theramex in collaboration with Kissei.

4) Opigolix (ASP1707, Astellas Pharma)

Opigolix remains under clinical investigation and has yet to receive formal regulatory approval for commercial distribution; development was discontinued globally in 2018 after completion of phase II trials for endometriosis and rheumatoid arthritis. A meta-analysis comparing the four oral GnRH formulations, elagolix, relugolix, linzagolix, and ASP1707, confirmed that 15 mg of has similar efficacy to 400 mg of elagolix in alleviating pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea [39].

Adjunct low-dose hormone ABT, incorporating estradiol (E2) and progestins, is frequently required in conjunction with oral GnRH antagonist treatment to mitigate menopausal symptoms and preserve bone density. This approach aligns with the “estradiol threshold hypothesis,” which suggests that partial suppression of E2 is adequate for controlling endometriosis symptoms while minimizing menopausal adverse effects. The recommended range of estradiol is 20 - 50 pg/mL for symptom control [40, 41].

Application of oral GnRH antagonists in endometriosis treatment

Efficacy in relieving EAP

In 2017, Taylor et al published findings from two phase III clinical trials, Elaris EM-I and Elaris EM-II, which were randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled studies conducted over 6 months. Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: a low-dose regimen (150 mg once daily), a high-dose regimen (200 mg twice daily), or a placebo control. The study aimed to assess the effects of elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist, on dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain in individuals diagnosed with endometriosis [42]. This study enrolled 1,689 individuals aged 18 to 49 who had experienced moderate-to-severe endometriosis-related pain within the past 10 years. Those assigned to the experimental groups received either 150 or 200 mg of elagolix, whereas the control group was given a placebo. The primary study endpoint was the clinical response rate for dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain assessed at the 3-month mark. The secondary endpoints included assessments of pain score variations over a 6-month period, as well as the frequency of rescue analgesic use. Results indicated that both dosage regimens of elagolix led to substantial reductions in dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain, with these benefits sustained over a 6-month period. Compared to both the low-dose and placebo arms, the high-dose group achieved markedly superior pain relief. Once the initial trial established elagolix’s short-term effectiveness in reducing endometriosis-related pain, subsequent studies shifted their focus to assessing its long-term efficacy and safety [43]. The Elaris EM-III and EM-IV extension trials maintained the double-blind, placebo-controlled methodology of previous studies to assess the impact of sustained 12-month elagolix therapy. A total of 569 women who had previously completed the initial trials were enrolled in these studies and were subsequently assigned to receive either 150 mg of elagolix once daily or 200 mg twice daily. During the 12-month treatment phase, the 200 mg group demonstrated a dysmenorrhea response rate of 78%, while the response rates for non-menstrual pelvic pain and dyspareunia were 69% and 60%, respectively. For those in the 150 mg treatment group, the observed response rates were 52% for dysmenorrhea, 67% for non-menstrual pelvic pain, and 45% for dyspareunia. These response rates were similar to those of the short-term trials, demonstrating the continued pain-relieving effects of elagolix. Additionally, the use of rescue analgesics significantly decreased during the treatment period: opioid use decreased by an average of 45% in the 150 mg group, and by more than 65% in the 200 mg group. The findings from this extended trial confirmed the long-term efficacy of elagolix in controlling EAP.

In 2021, Osuga et al carried out a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety and therapeutic efficacy of relugolix in the treatment of EAP over a 24-week period [44]. Conducted across 101 clinical centers in Japan, this trial recruited premenopausal women who were randomly allocated to receive different doses of relugolix or a placebo for a duration of 12 weeks. Participants were assigned to one of several treatment regimens, including daily oral relugolix at doses of 10, 20, or 40 mg; a placebo; or a monthly 3.75 mg injection of leuprolide acetate, a GnRH agonist. The primary endpoints focused on safety, with particular attention to BMD changes and the occurrence of adverse events over the course of treatment. Secondary outcomes encompassed the assessment of pain relief using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The study concluded that relugolix exhibited good overall tolerability, with its analgesic efficacy comparable to that of leuprolide. In a subsequent investigation, Osuga et al expanded on prior findings by analyzing the dose-response relationship of relugolix over a 12-week treatment period [45]. The results reinforced that its effectiveness in reducing endometriosis-related pain was contingent on dosage.

The 2020 EDELWEISS trial examined the therapeutic effects of linzagolix on EAP [46]. This international, multicenter study employed a randomized, double-blind design and included women aged 18 to 45 with surgically confirmed moderate-to-severe EAP. Participants were randomly assigned to receive linzagolix at doses of 50, 75, 100, or 200 mg, or a placebo, administered once daily over a 24-week period. The primary endpoint assessed the proportion of patients experiencing at least a 30% reduction in overall pelvic pain by week 12. Secondary endpoints included changes in dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain, fluctuations in serum estradiol levels, the incidence of amenorrhea, and quality-of-life assessments. Results indicated that doses of 75 mg or higher were associated with a substantial decrease in EAP.

A phase II placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial with a multicenter, parallel-group design was conducted between December 2012 and July 2015 across Europe and Japan to assess the efficacy and safety of opigolix in treating endometriosis-related pelvic pain [47]. A total of 912 women experiencing pelvic pain were enrolled in this trial, with 540 completing the study. Participants were randomly assigned to receive either a placebo, one of several opigolix doses (3, 5, 10, or 15 mg), or leuprolide. The primary endpoint was assessed as the change in the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) score for overall pelvic pain over a 12-week period. Secondary outcomes included variations in NRS scores for dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain, alongside evaluations of serum estradiol levels and BMD. The findings demonstrated a dose-dependent analgesic effect of opigolix, with higher doses providing greater pain relief.

Effect on lesion size

In 2021, secondary clinical outcomes from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Harada et al showed that once-daily oral relugolix (40 mg) was effective over a 24-week period in treating endometriosis-related lesions (including endometriotic cysts) [48]. Conducted across 42 clinical centers in Japan, this trial recruited women diagnosed with endometriosis or ovarian endometriotic cysts. Participants were administered either a daily 40 mg dose of relugolix or a monthly injection of 3.75 mg leuprolide. The primary outcome was defined as the variation in the highest VAS score. Findings from the study indicated that relugolix exhibited a therapeutic efficacy comparable to that of leuprolide. In the relugolix group, ovarian endometriotic cyst volumes declined by 12.26 ± 17.52 cm3, compared to a decrease of 14.10 ± 18.81 cm3 in the leuprolide group, demonstrating that both treatments achieved similar reductions in cyst volume. During treatment, both relugolix and leuprolide showed similar safety profiles, with comparable drug-related adverse events. However, patients in the relugolix group experienced earlier recovery of menstruation compared to those in the leuprolide group.

In 2023, Tezuka et al conducted an investigation utilizing an experimental rat model to evaluate the effects of linzagolix on endometriosis [49]. To establish an endometriosis model, the study utilized autologous transplantation of endometrial tissue. The treatment group was administered varying doses of linzagolix (50, 100, and 200 mg/kg). Study results demonstrated that linzagolix administration at doses of 50 mg/kg or higher led to a substantial decrease in cyst volume. Relative to the control group, the cyst volume was significantly reduced. Linzagolix also demonstrated stronger suppression effects at lower doses when compared to the dienogest group. The study indicated that linzagolix reduced endometriotic cyst volume by inhibiting GnRH signaling and lowering serum estradiol (E2) levels.

Currently, there is a lack of high-quality clinical studies directly assessing the impact of oral GnRH antagonists on the volume of deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) lesions. In contrast, a study evaluating the effect of the oral progestin dienogest on DIE lesion volume found that, after 12 months of continuous treatment, there was no significant reduction in the volume of rectovaginal lesions [50]. This suggests that while hormonal therapy may alleviate symptoms associated with DIE, its effect on lesion size remains uncertain. Although oral GnRH antagonists have shown potential efficacy in relieving DIE-related pain, their influence on lesion volume is not yet clearly defined. Further high-quality research is necessary to evaluate their role and safety in the treatment of DIE.

Improvement in quality of life

Diamond et al utilized the Endometriosis Health Profile-5 (EHP-5) to assess five key health domains: pain, emotional well-being, self-image, social support, and feelings of control and helplessness [51]. The study demonstrated significant improvements across all assessed domains, with the most notable effects occurring in the 150 mg treatment group. By week 12, the reduction in pain scores within this cohort was statistically superior to that of the placebo group. Additionally, Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scores were significantly higher among individuals receiving elagolix compared to those in the placebo group. At week 12, the mean PGIC rating for the elagolix cohort indicated a “much improved” status, whereas the placebo group showed only a “slightly improved” outcome. This improvement persisted throughout the 24-week study, indicating that elagolix significantly contributed to enhancing the quality of life in women with endometriosis. Moreover, patients receiving elagolix also experienced a noticeable decrease in fatigue [52].

Harada et al reported that after 24 weeks of relugolix treatment, significant improvements were noted across multiple health dimensions, including pain, emotional well-being, self-image, social support, and perceptions of control and helplessness. Furthermore, improvements in work productivity and activity limitations also indicated the positive impact of relugolix on work efficiency and daily activities. Compared to leuprolide acetate, patients using relugolix experienced faster menstrual recovery, which is a significant advantage for women planning to conceive after treatment [48].

In the EDELWEISS trial, according to the EHP-30 scores, significant improvements were observed in pain, control, and helplessness in all dose groups. Notably, improvements in emotional well-being, social support, and self-image were observed only at the higher 200 mg dose, underscoring the beneficial effects of linzagolix on multiple aspects of quality of life. PGIC assessments indicated that patients treated with linzagolix experienced significant improvements following 12 weeks of therapy, with the most pronounced benefits observed in the 75 and 200 mg dose cohorts [46].

Adverse reactions

The most frequently observed adverse events with elagolix are vasomotor symptoms, and their occurrence is dependent on the dose administered [42]. Other common adverse reactions, such as the effect on BMD, also show a dose-dependent relationship, with women receiving higher doses of elagolix experiencing a greater reduction in bone density.

In Osuga et al’s study, the frequency of treatment-emergent adverse events (TATEs) during relugolix therapy was comparable to that observed with leuprolide [44, 45]. The most frequently observed TATEs comprised nasopharyngitis, headaches, menstrual irregularities, sweating, BMD loss, and hot flashes.

The most commonly reported adverse effects associated with linzagolix were hot flashes and headaches. Additionally, the study found that BMD loss averaged below 1% in the 75 mg group, while the 200 mg group exhibited a 2.6% reduction [46].

A meta-analysis confirmed that the discontinuation rate and adverse reaction rate for opigolix were lower than those for elagolix and relugolix, but further experimental confirmation is needed [39].

Impact of ABT on drug use

Carr et al conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial to assess the efficacy and safety of elagolix, both as monotherapy and in combination with ABT, in women with heavy menstrual bleeding due to uterine fibroids [53]. The trial included two elagolix dosing regimens, 300 mg twice daily and 600 mg once daily, alongside a placebo group. Additionally, participants were assigned to either an elagolix-only group or one of two ABT groups: a low-dose regimen (0.5 mg estradiol/0.1 mg norethindrone acetate) or a high-dose regimen (1.0 mg estradiol/0.5 mg norethindrone acetate). While elagolix treatment was linked to bone density reduction, the administration of high-dose ABT (1.0 mg estradiol/0.5 mg norethindrone acetate) effectively minimized this effect. Hot flashes were frequently reported as an adverse effect; however, the addition of ABT helped alleviate this symptom. Ongoing clinical studies continue to assess the efficacy and safety of elagolix in combination with ABT for treating EAP (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT03213457).

Two parallel phase III randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (SPIRIT 1 and SPIRIT 2) were conducted to evaluate the efficacy of daily oral relugolix combination therapy in alleviating EAP [54]. Women aged 18 - 50 with endometriosis, confirmed either surgically or visually (with or without histological validation), were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive a daily oral placebo, relugolix combination therapy (relugolix 40 mg, estradiol 1 mg, and norethindrone acetate 0.5 mg), or a delayed-start relugolix combination therapy. Results demonstrated that 75% of patients receiving relugolix combination therapy exhibited a positive response in dysmenorrhea, compared with 27% in the placebo group in SPIRIT 1 and 30% in SPIRIT 2. Additionally, relugolix combination therapy significantly alleviated non-menstrual pelvic pain. In SPIRIT 1, 58% of patients exhibited a response, compared with 40% in the placebo group, whereas in SPIRIT 2, response rates were 66% and 43% for the relugolix combination and placebo groups, respectively. At 24 weeks, the difference in BMD changes between the relugolix combination therapy and placebo groups at both the lumbar spine and total hip remained below 1%. These results indicate that a daily regimen of relugolix combination therapy provides substantial relief from EAP while maintaining a favorable safety profile.

The EDELWEISS trial demonstrated that a higher dose (200 mg/day) provided enhanced pelvic pain relief; however, the associated BMD reduction necessitated the implementation of ABT [46]. A study conducted in healthy premenopausal women examined the effects of linzagolix in combination with ABT on vaginal bleeding patterns [55]. It was found that initiating both treatments simultaneously resulted in better bleeding control than delaying ABT initiation. This treatment strategy was also associated with the absence of hot flashes and lower mean estradiol levels.

| Conclusions | ▴Top |

Across 13 trials informing this review, most pivotal phase III studies of elagolix, relugolix + add-back, and linzagolix scored low on all RoB 2 domains, whereas three elagolix extensions and one open-label relugolix study carried attrition- or blinding-related concerns; a single phase I linzagolix trial and one animal experiment were high or unclear for performance and detection bias. GRADE appraisal placed dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain outcomes in the moderate-certainty tier for elagolix and linzagolix and in the moderate-to-high tier for relugolix, downgrading mainly for imprecision. Hypo-estrogenic adverse events and bone-loss data were likewise moderate, with relugolix + add-back showing the smallest lumbar-spine change (-0.7% at 24 weeks) and elagolix 200 mg twice-daily the largest (-5% to 15%). Evidence for lesion regression and very-long extension phases remained low-to-very-low, urging rigorously blinded, head-to-head, long-term imaging trials to secure higher-certainty estimates (Supplementary Materials 1-6, jocmr.elmerjournals.com).

Among existing therapies, COCs and progestin-only regimens share common adverse effects such as breast tenderness, nausea, mood swings, and weight gain. These reactions have been shown to reduce quality of life and prompt treatment discontinuation in 64.6% of users, thereby compromising adherence [56, 57]. By contrast, the adverse events associated with oral GnRH antagonists stem chiefly from hypo-estrogenism, such as hot flushes and loss of BMD; nevertheless, they can be mitigated by ABT. Progestin-containing agents may also increase the frequency of abnormal uterine bleeding, whereas oral GnRH antagonists are linked to lower rates of moderate-to-severe uterine bleeding and breakthrough bleeding [58]. In contrast, oral GnRH antagonists demonstrate a lower prevalence of moderate-to-severe uterine bleeding and breakthrough bleeding. Moreover, when used in conjunction with ABT, oral GnRH antagonists present several advantages over GnRH agonists combined with ABT: 1) Oral administration: This eliminates the need for injections, improving patient convenience, adherence, and satisfaction. 2) No flare effect: GnRH agonists cause a “flare effect” during the initial treatment phase, which can worsen symptoms, whereas GnRH antagonists do not induce this effect, avoiding the side effects associated with the temporary rise in hormone levels. 3) Dose-dependent reduction of ovarian steroid secretion: GnRH antagonists offer more flexibility in adjusting the treatment dose to achieve better hormonal control. 4) Rapid reversibility: GnRH antagonists allow for quicker restoration of ovarian function after discontinuation, making them suitable for patients who need a rapid return to normal hormone levels. Oral non-peptide GnRH antagonists have emerged as a novel therapeutic approach for alleviating EAP [46, 59]. These agents significantly alleviate pain and contribute to an improved quality of life for individuals with endometriosis. When combined with ABT, they can be used for long-term management. However, although GnRH antagonists can induce atrophy or dormancy in endometriotic lesions, these lesions may still undergo low-level proliferation, cell division, and ultimately acquire mutations. Further investigation is required to evaluate the potential risk of malignant transformation linked to prolonged GnRH antagonist therapy in responsive patients [60]. Additional trials are required to determine if the subset of women who are resistant to estrogen and progestins is the same as those who do not respond to oral GnRH antagonists [61]. Additionally, studies comparing GnRH antagonists with first-line treatment options, as well as evaluations of the long-term efficacy and safety profiles of different GnRH antagonists, are warranted. Given the substantial financial burden of endometriosis treatments, further research is needed to explore alternative therapeutic strategies aimed at improving patients’ quality of life [62].

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Summary of Findings: Efficacy in Relieving Endometriosis-Associated Pain.

Suppl 2. Summary of Findings: Effect on Lesion Size.

Suppl 3. Summary of Findings: Improvement in Quality of Life.

Suppl 4. Summary of Findings: Adverse Reactions.

Suppl 5. Summary of Findings: Impact of Add-Back Therapy (ABT) on Drug Use.

Suppl 6. Risk of Bias in Included Studies.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

This study was supported by the 2024 Young and Middle-aged Teacher Training Action Project of Anhui Province (Project No. YQZD2024030) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant No. 2022-45-0901).

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Author Contributions

Jing Yi Wang wrote the article. Jin Ding provided substantial information on oral GnRH antagonists. Yan Zhang provided critical revisions and contributed to the conceptual framework and interpretation of the results. Jing Yi Wang searched for references. Jin Ding assisted in writing. Jing Yi Wang and Jin Ding designed the article and assisted in reference collection and writing.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Abbreviations

ABT: add-back therapy; ASP1707: opigolix; BMD: bone mineral density; COCs: combined oral contraceptives; DIE: deep infiltrating endometriosis; EAP: endometriosis-associated pain; FSH: follicle-stimulating hormone; GnRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone; HPO: hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian; LH: luteinizing hormone; NRS: Numerical Rating Scale; PGIC: Patient Global Impression of Change; TATE: treatment-emergent adverse event; VAS: Visual Analog Scale

| References | ▴Top |

- Lagana AS, Garzon S, Gotte M, Vigano P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Martin DC. The pathogenesis of endometriosis: molecular and cell biology insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5615.

doi pubmed - Bonavina G, Taylor HS. Endometriosis-associated infertility: From pathophysiology to tailored treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1020827.

doi pubmed - Namazi M, Behboodi Moghadam Z, Zareiyan A, Jafarabadi M. Exploring the impact of endometriosis on women's lives: A qualitative study in Iran. Nurs Open. 2021;8(3):1275-1282.

doi pubmed - Horne AW, Missmer SA. Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis. BMJ. 2022;379:e070750.

doi pubmed - Shi J, Tan X, Feng G, Zhuo Y, Jiang Z, Banda S, Wang L, et al. Research advances in drug therapy of endometriosis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1199010.

doi pubmed - Donnez J, Dolmans MM. GnRH antagonists with or without add-back therapy: a new alternative in the management of endometriosis? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11342.

doi pubmed - Donnez J, Stratopoulou CA, Dolmans MM. Uterine Adenomyosis: From Disease Pathogenesis to a New Medical Approach Using GnRH Antagonists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(19):9941.

doi pubmed - Crump J, Suker A, White L. Endometriosis: A review of recent evidence and guidelines. Aust J Gen Pract. 2024;53(1-2):11-18.

doi pubmed - Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, Kohlmeier A, et al. Endometriosis. Endocr Rev. 2019;40(4):1048-1079.

doi pubmed - Veth VB, van de Kar MM, Duffy JM, van Wely M, Mijatovic V, Maas JW. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;6(6):CD014788.

doi pubmed - Bulun SE, Yildiz S, Adli M, Chakravarti D, Parker JB, Milad M, Yang L, et al. Endometriosis and adenomyosis: shared pathophysiology. Fertil Steril. 2023;119(5):746-750.

doi pubmed - Vercellini P, Buggio L, Berlanda N, Barbara G, Somigliana E, Bosari S. Estrogen-progestins and progestins for the management of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2016;106(7):1552-1571.e1552.

doi pubmed - Mikus M, Sprem Goldstajn M, Lagana AS, Vukorepa F, Coric M. Clinical efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and safety of the available medical options in the treatment of endometriosis-related pelvic pain: a scoping review. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(9):1315.

doi pubmed - Becker CM, Bokor A, Heikinheimo O, Horne A, Jansen F, Kiesel L, King K, et al. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis. Hum Reprod Open. 2022;2022(2):hoac009.

doi pubmed - Ali M, Raslan M, Ciebiera M, Zareba K, Al-Hendy A. Current approaches to overcome the side effects of GnRH analogs in the treatment of patients with uterine fibroids. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2022;21(4):477-486.

doi pubmed - Dolmans MM, Cacciottola L, Donnez J. Conservative management of uterine fibroid-related heavy menstrual bleeding and infertility: time for a deeper mechanistic understanding and an individualized approach. J Clin Med. 2021;10(19):4389.

doi pubmed - Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Endometriosis and medical therapy: from progestogens to progesterone resistance to GnRH antagonists: a review. J Clin Med. 2021;10(5):1085.

doi pubmed - Neill JD. GnRH and GnRH receptor genes in the human genome. Endocrinology. 2002;143(3):737-743.

doi pubmed - Donnez J, Taylor RN, Taylor HS. Partial suppression of estradiol: a new strategy in endometriosis management? Fertil Steril. 2017;107(3):568-570.

doi pubmed - Grundker C, Gunthert AR, Millar RP, Emons G. Expression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone II (GnRH-II) receptor in human endometrial and ovarian cancer cells and effects of GnRH-II on tumor cell proliferation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(3):1427-1430.

doi pubmed - Huang F, Wang H, Zou Y, Liu Q, Cao J, Yin T. Effect of GnRH-II on the ESC proliferation, apoptosis and VEGF secretion in patients with endometriosis in vitro. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6(11):2487-2496.

pubmed - Clemenza S, Sorbi F, Noci I, Capezzuoli T, Turrini I, Carriero C, Buffi N, et al. From pathogenesis to clinical practice: Emerging medical treatments for endometriosis. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2018;51:92-101.

doi pubmed - Ali M, A RS, Al Hendy A. Elagolix in the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding associated with uterine fibroids in premenopausal women. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2021;14(4):427-437.

doi pubmed - Rocca ML, Palumbo AR, Lico D, Fiorenza A, Bitonti G, D'Agostino S, Gallo C, et al. Relugolix for the treatment of uterine fibroids. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2020;21(14):1667-1674.

doi pubmed - Dababou S, Garzon S, Lagana AS, Ferrero S, Evangelisti G, Noventa M, D'Alterio MN, et al. Linzagolix: a new GnRH-antagonist under investigation for the treatment of endometriosis and uterine myomas. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2021;30(9):903-911.

doi pubmed - National Center for Biotechnology Information. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 11250647, Elagolix [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): NCBI; [cited May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Elagolix.

- PubChem [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 10348973, Relugolix [cited May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Relugolix.

- PubChem [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 16656889, Linzagolix [cited May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Linzagolix.

- PubChem [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US), National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2004–. PubChem Compound Summary for CID 135565248, Opigolix [cited May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Opigolix.

- Food and Drug Administration (US). ORILISSA™ (Elagolix) tablets, for oral use: initial U.S. approval. 2018 [Internet]. 2022 [cited Dec 17, 2022]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/210450s000lbl.pdf.

- AbbVie. AbbVie Receives Health Canada Approval of ORILISSA™ (elagolix) for the Treatment of Moderate to Severe Pain Associated with Endometriosis [Internet]. 2018 [cited May 18, 2024]. Available from: https://www.abbvie.ca/content/dam/abbvie-dotcom/ca/en/documents/press-releases/2018-Oct-5_Elagolix-Health-Canada-Release_EN.pdf.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves relugolix for advanced prostate cancer. 2020 Dec 18. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-relugolix-advanced-prostate-cancerjhoponline.com+2.

- Myovant Sciences and Pfizer. Myovant Sciences and Pfizer Receive U.S. FDA approval of MYFEMBREE®, a once-daily treatment for the management of moderate to severe pain associated with endometriosis. Aug 5, 2022. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/myovant-sciences-and-pfizer-receive-us-fda-approval.

- European Medicines Agency. Ryeqo: EPAR - Public assessment report. Jul 16, 2021. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/assessment-report/ryeqo-epar-public-assessment-report_en.pdf.

- Gedeon Richter Plc. European Commission approves the commercialisation of RYEQO® for the Symptomatic Treatment of Endometriosis. Nov 2, 2023. Available from: https://www.gedeonrichter.com/-/media/sites/hq/documents/investors/announcements/2023/20231102_bus_whc_reg_relugolix/rch231102er02e.pdf.

- Pohl O, Baron K, Riggs M, French J, Garcia R, Gotteland JP. A model-based analysis to guide gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist use for management of endometriosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88(5):2359-2371.

doi pubmed - Theramex. Theramex announces European Commission marketing authorization for Yselty® (linzagolix), an oral GnRH antagonist, for the treatment of symptoms of uterine fibroids [Internet]. 2022 [cited May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://www.theramex.com/news/theramex-announces-european-commission-marketing-authorization-for-yselty-linzagolix-an-oral-gnrh-antagonist-for-the-treatment-of-symptoms-of-uterine-fibroids/.

- European Medicines Agency. Yselty: EPAR - Public assessment report [Internet]. 2024 [cited May 18, 2025]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/yselty.

- Xin L, Ma Y, Ye M, Chen L, Liu F, Hou Q. Efficacy and safety of oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonists in moderate-to-severe endometriosis-associated pain: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023;308(4):1047-1056.

doi pubmed - Barbieri RL. Hormone treatment of endometriosis: the estrogen threshold hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(2):740-745.

doi pubmed - Riggs MM, Bennetts M, van der Graaf PH, Martin SW. Integrated pharmacometrics and systems pharmacology model-based analyses to guide GnRH receptor modulator development for management of endometriosis. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2012;1(10):e11.

doi pubmed - Taylor HS, Giudice LC, Lessey BA, Abrao MS, Kotarski J, Archer DF, Diamond MP, et al. Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain with Elagolix, an Oral GnRH Antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):28-40.

doi pubmed - Long-term outcomes of elagolix in women with endometriosis: results from two extension studies: correction. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(6):1507-1508.

doi pubmed - Osuga Y, Seki Y, Tanimoto M, Kusumoto T, Kudou K, Terakawa N. Relugolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor antagonist, in women with endometriosis-associated pain: phase 2 safety and efficacy 24-week results. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):250.

doi pubmed - Osuga Y, Seki Y, Tanimoto M, Kusumoto T, Kudou K, Terakawa N. Relugolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist, reduces endometriosis-associated pain in a dose-response manner: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2021;115(2):397-405.

doi pubmed - Donnez J, Taylor HS, Taylor RN, Akin MD, Tatarchuk TF, Wilk K, Gotteland JP, et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with linzagolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone-antagonist: a randomized clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2020;114(1):44-55.

doi pubmed - D'Hooghe T, Fukaya T, Osuga Y, Besuyen R, Lopez B, Holtkamp GM, Miyazaki K, et al. Efficacy and safety of ASP1707 for endometriosis-associated pelvic pain: the phase II randomized controlled TERRA study. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(5):813-823.

doi pubmed - Harada T, Osuga Y, Suzuki Y, Fujisawa M, Fukui M, Kitawaki J. Relugolix, an oral gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor antagonist, reduces endometriosis-associated pain compared with leuprorelin in Japanese women: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, noninferiority study. Fertil Steril. 2022;117(3):583-592.

doi pubmed - Tezuka M, Tsuchioka K, Kobayashi K, Kuramochi Y, Kiguchi S. Suppressive effects of linzagolix, a novel non-peptide antagonist of gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors, in experimental endometriosis model rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2023;50(7):610-617.

doi pubmed - Ma Y, Wang WX, Zhao Y. Dienogest in conjunction with GnRH-a for postoperative management of endometriosis. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1373582.

doi pubmed - Diamond MP, Carr B, Dmowski WP, Koltun W, O'Brien C, Jiang P, Burke J, et al. Elagolix treatment for endometriosis-associated pain: results from a phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Reprod Sci. 2014;21(3):363-371.

doi pubmed - Surrey ES, Soliman AM, Agarwal SK, Snabes MC, Diamond MP. Impact of elagolix treatment on fatigue experienced by women with moderate to severe pain associated with endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2019;112(2):298-304.e293.

doi pubmed - Carr BR, Stewart EA, Archer DF, Al-Hendy A, Bradley L, Watts NB, Diamond MP, et al. Elagolix alone or with add-back therapy in women with heavy menstrual bleeding and uterine leiomyomas: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(5):1252-1264.

doi pubmed - Giudice LC, As-Sanie S, Arjona Ferreira JC, Becker CM, Abrao MS, Lessey BA, Brown E, et al. Once daily oral relugolix combination therapy versus placebo in patients with endometriosis-associated pain: two replicate phase 3, randomised, double-blind, studies (SPIRIT 1 and 2). Lancet. 2022;399(10343):2267-2279.

doi pubmed - Lee J, Park HJ, Yi KW. Dienogest in endometriosis treatment: A narrative literature review. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2023;50(4):223-229.

doi pubmed - Pohl O, Marchand L, Bell D, Gotteland JP. Effects of combined GnRH receptor antagonist linzagolix and hormonal add-back therapy on vaginal bleeding-delayed add-back onset does not improve bleeding pattern. Reprod Sci. 2020;27(4):988-995.

doi pubmed - Morimont L, Haguet H, Dogne JM, Gaspard U, Douxfils J. Combined oral contraceptives and venous thromboembolism: review and perspective to mitigate the risk. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:769187.

doi pubmed - Carr B, Giudice L, Dmowski WP, O'Brien C, Jiang P, Burke J, Jimenez R, et al. Elagolix, an Oral GnRH antagonist for endometriosis-associated pain: a randomized controlled study. J Endometr Pelvic Pain Disord. 2013;5(3):105-115.

doi pubmed - Cacciottola L, Donnez J, Dolmans MM. Can endometriosis-related oxidative stress pave the way for new treatment targets? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(13):7138.

doi pubmed - Guo SW. Cancer-associated mutations in endometriosis: shedding light on the pathogenesis and pathophysiology. Hum Reprod Update. 2020;26(3):423-449.

doi pubmed - Vercellini P, Vigano P, Barbara G, Buggio L, Somigliana E, Luigi Mangiagalli' Endometriosis Study G. Elagolix for endometriosis: all that glitters is not gold. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(2):193-199.

doi pubmed - Melyda M, Monahan M, Cooper KG, Bhattacharya S, Daniels JP, Cheed V, Middleton L, et al. Cost-effectiveness of long-acting progestogens versus the combined oral contraceptives pill for preventing recurrence of endometriosis-related pain following surgery: an economic evaluation alongside the PRE-EMPT trial. BMJ Open. 2024;14(12):e088072.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.