| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 000, Number 000, January 2026, pages 000-000

Assessment of Social Functioning in Patients With Schizophrenia and Their First-Degree Relatives

Takamitsu Shimadaa, b, c , Hiroaki Kiharaa, Yusuke Nittaa, Tatsuya Nagasawaa, Mitsuru Hasegawab, Yoshiki Maedab, Yasuhiro Kawasakia, Takashi Ueharaa

aDepartment of Neuropsychiatry, Kanazawa Medical University, Uchinada, Kahoku-gun, Ishikawa 920-0293, Japan

bMedical Corporation Sekijinkai Okabe Hospital, Kanazawa, Ishikawa 921-8114, Japan

cCorresponding Author: Takamitsu Shimada, Department of Neuropsychiatry, Kanazawa Medical University, Uchinada, Kahoku-gun, Ishikawa 920-0293, Japan

Manuscript submitted October 26, 2025, accepted December 29, 2025, published online January 4, 2026

Short title: Genetic Contributions to Schizophrenia

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6431

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Impaired social functioning is one of the core symptoms of schizophrenia (SCZ). Genetic factors have also been implicated in SCZ. To contribute to the discussion on the involvement of genetic factors in SCZ, we evaluated the social functioning of first-degree relatives (FR) of patients with SCZ.

Methods: This was a non-interventional observational study. We examined social functioning using the Japanese version of the Social Functioning Scale (SFS-J) in three groups: SCZ, SCZ FR, and healthy controls (HC). The effects of the groups (SCZ, FR, and HC) on social functioning were evaluated using analysis of covariance. In addition, the cutoff value for SCZ in the SFS total score was calculated, and the trend in the proportion of individuals below the cutoff value in each group was evaluated.

Results: Data from 256 subjects (SCZ (n = 44), FR (n = 26), and HC (n = 186)) were analyzed. Group, years of education, intelligence quotient (IQ), and sex were found to be significant factors affecting SFS total scores. The proportion of SFS scores < 140 (the cutoff value for SCZ) was 9.1% in HC, 57.7% in FR, and 95.4% in SCZ, showing a continuous increase in the proportion of SFS scores < 140 across the three groups (P < 0.0001).

Conclusions: In social functioning assessed by SFS, the score for FR was intermediate between those of SCZ and HC. The results of this study suggest that genetic factors may influence social functioning scores in SCZ and FR.

Keywords: Schizophrenia; First-degree relatives; Social functioning; Japanese version of Social Functioning Scale; Genetic involvement

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Schizophrenia (SCZ) is a chronic, relapsing mental disorder characterized by positive symptoms, such as hallucinations and delusions; negative symptoms, such as loss of motivation and emotional expression; and cognitive impairment [1]. The treatment outcome is not always satisfactory, with Jaaskelainen et al reporting that only 13.5% of patients achieved the clinical and social recovery criteria [2]. According to a domestic survey, 70.8% of patients were unmarried, 48.9% were unemployed, and the quality of life (QOL) was particularly low when they also had sleep disorders, depression, or anxiety disorders [3]. SCZ most often develops in late adolescence or early adulthood [4], and its lifetime prevalence is reported to be 0.87% overseas and 0.59% in Japan [3, 5].

Functional outcomes refer to the ability to cope with everyday life events, such as living independently, managing finances, employment, and social activities [6, 7]; these are often impaired in SCZ. SCZ also involves impairments in social functioning, defined as an individual’s ability to adequately perform everyday social tasks and maintain an appropriate social life [8]. Social dysfunction is defined as the inability to adapt flexibly to various social situations and demands [3]. Impaired social functioning is a core symptom of SCZ [9]. Impaired social functions exist regardless of the illness course (first episode or chronic) of SCZ [10, 11]. Individuals at a clinically high risk for psychosis show impairments in social functions even during the prepsychotic phase of SCZ, suggesting that social deficits are present long before the onset of psychotic symptoms [12]. Premorbid impairments in social function showed familial aggregation, implying the possible heritability of social function [13].

Genetic factors are involved in the development of SCZ, with an estimated heritability of 64-81% [14, 15]. Studies of families and twins of patients with SCZ have shown that the more genes shared, such as between first-degree parents or identical twins, the higher the risk of developing SCZ [16, 17]. In particular, the involvement of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and copy number variants has been a focus of research; Ripke et al. reported that more than 8,000 SNPs may be involved in SCZ [18]. Although no SNPs have been proven to cause SCZ, it has been suggested that SNPs in ZNF804A may affect cognitive function depending on the patient’s intelligence quotient (IQ) [19, 20]. In a study of patients with SCZ and their relatives, Los et al found that the neurocognitive function of unaffected siblings was intermediate between those of patients with SCZ and healthy controls (HC) [21]. In addition, Lin et al reported that the first-degree relatives (FR) of patients with SCZ who did not develop SCZ had significantly lower prospective memory than that of HC [22]. Furthermore, highly reproducible endophenotypes in SCZ, such as P50, P300, and mismatch negativity, which are electrophysiological indices in response to specific brain stimuli, have been reported [23, 24]. Nevertheless, Kerr-Gaffney et al reported that FR of SCZ patients did not differ significantly from HC in terms of impulsivity, a concept that includes both cognitive and behavioral components [25], suggesting that there may not be clear differences between SCZ and its FRs depending on the indicators. To date, there has been insufficient research into the social functioning of patients with SCZ and their relatives. Against this background, we investigated the social functioning of patients with SCZ, their FR, and HC.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and subject

This was a non-interventional observational study. Patients with SCZ and FR were recruited from both the outpatient and inpatient populations at Kanazawa Medical University Hospital and Okabe Hospital. Patients with SCZ were diagnosed by at least two trained psychiatrists based on unstructured clinical interviews, medical records, and clinical conferences. Patients were diagnosed according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Unaffected FR were evaluated using the non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) to exclude individuals with a current or history of receiving psychiatric services or psychiatric medications. HC were recruited through local advertisements and from staff at Okabe hospitals; they were also evaluated using the non-patient version of the SCID to exclude individuals who had current or past contact with psychiatric services, had received psychiatric medications, or had a family history of any neuropsychiatric diseases within second-degree relatives. Participants were excluded if they had neurological or medical conditions that could affect the central nervous system, including atypical headache, head trauma with loss of consciousness, thyroid disease, chronic hepatic disease, chronic lung disease, kidney disease, active cancer, cerebrovascular disease, epilepsy, seizures, substance-related disorders, or intellectual disorders.

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants after the procedures were fully explained. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Kanazawa Medical University (approval number: 1716).

Endpoints

In this study, social functioning was assessed using the Social Functioning Scale (SFS) [26]. This study examined: 1) the impact of differences between groups (SCZ, FR, and HC) on social functioning; 2) trends in social functioning among each group; 3) a comparison of the SFS subscales among each group; and 4) correlation of SFS scores between patients with SCZ and their unaffected parents.

Assessment of premorbid IQ and social functioning

Premorbid IQ was assessed for each of the SCZ, FR, and HC groups using the Japanese Adult Reading Test 50 (JART50) [27]. Social function was assessed using the Japanese version of the Social Functioning Scale (SFS-J), which is a self-report questionnaire [28]. The SFS has seven subscales: 1) withdrawal (time spent alone, initiation of conversation, and social avoidance) with score range of 0–15; 2) interpersonal communication (number of friends/having a romantic partner and quality of communication) with score range of 0–12; 3) independence-performance (performance of skills necessary for independent living) with score range of 0–39; 4) independence-competence (ability to perform skills necessary for independent living) with score range of 0–39; 5) recreation (engagement in a range of common hobbies, interests, pastimes, etc.) with score range of 0–45; 6) prosocial activities (engagement in a range of common social activities, e.g., sport) with score range of 0–66; and 7) employment/occupation (engagement in productive employment or a structured program with daily activities) with score range of 0–10. The total score is the sum of the seven domain scores, with a score range of 0–226 [26]. A higher score indicates a higher level of social functioning.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were expressed as n (%), mean ± standard deviation (SD). The effect of group on social functioning was evaluated using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with the SFS total score as the dependent variable and sex, group, age, years of education, and JART50 as independent variables. The participants were divided into two groups: those with SCZ and others (FR and HC). The cutoff value for SCZ in the SFS total score was calculated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. The proportion of participants in each group whose SFS total score was below the cutoff value was evaluated for trends among the three groups using the Cochran-Armitage test. Multiple comparisons were performed among the three groups using the Kruskal-Wallis test for each score on the SFS subscale, and pairwise Wilcoxon tests were performed if significant differences were found. The association between SFS scores of patients with SCZ and their unaffected parents was assessed using the Spearman rank correlation coefficient. The significance level was set at 5%. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 18.0.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

| Results | ▴Top |

Subject background

Data from 256 subjects were analyzed. Among all, 37.5% of the subjects were male, with age of 48.0 ± 16.0 years, educational history of 13.5 ± 2.2 years, JART50-estimated IQ of 106.3 ± 9.2, and a SFS total score of 149.2 ± 36.2 (Table 1). There were significant differences among the three groups in terms of age, educational background, JART50 score, and SFS total score.

Click to view | Table 1. Subjects Background |

The impact of groups (SCZ, FR, and HC) on social functioning

Significant factors affecting the SFS total score were group, years of education, JART50 predicted IQ, and sex (Table 2). Factors that increased the SFS total score were HC, years of education, JART50 predicted IQ, and female sex, whereas factors that decreased it were FR, SCZ, and male sex. The difference (± standard error) in SFS total score was –27.3 ± 5.7 (P = 0.0067) between SCZ and FR, –30.9 ± 4.9 (P = 0.0004) between FR and HC, and –58.2 ± 4.1 (P < 0.0001) between SCZ and HC (Table 3).

Click to view | Table 2. Effect of Group (SCZ, FR, HC) on SFS Total Score: ANCOVA |

Click to view | Table 3. Difference in SFS Total Score Between Groups: Linear Contrast Test Based on ANCOVA |

Intergroup trends in social functioning

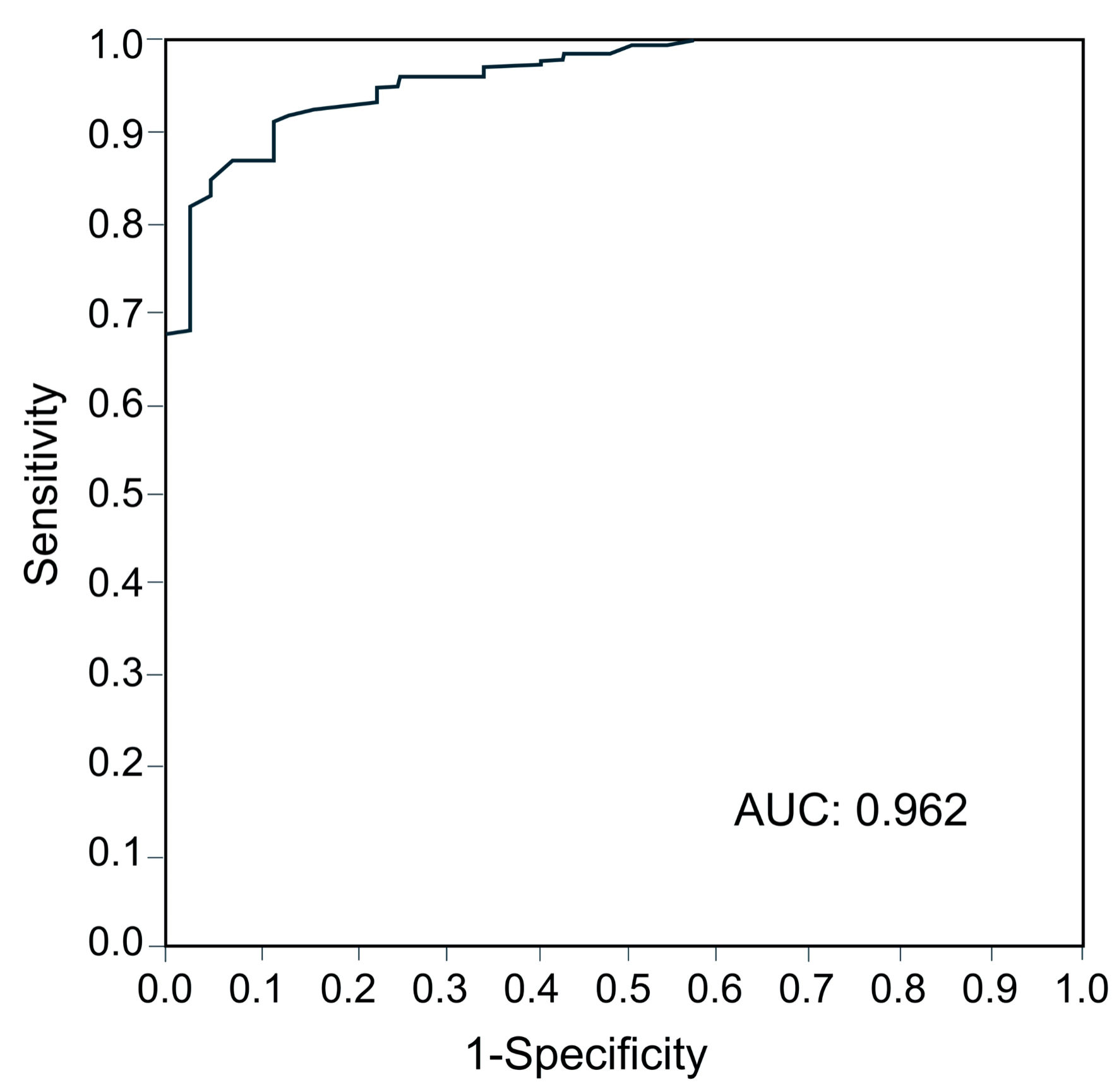

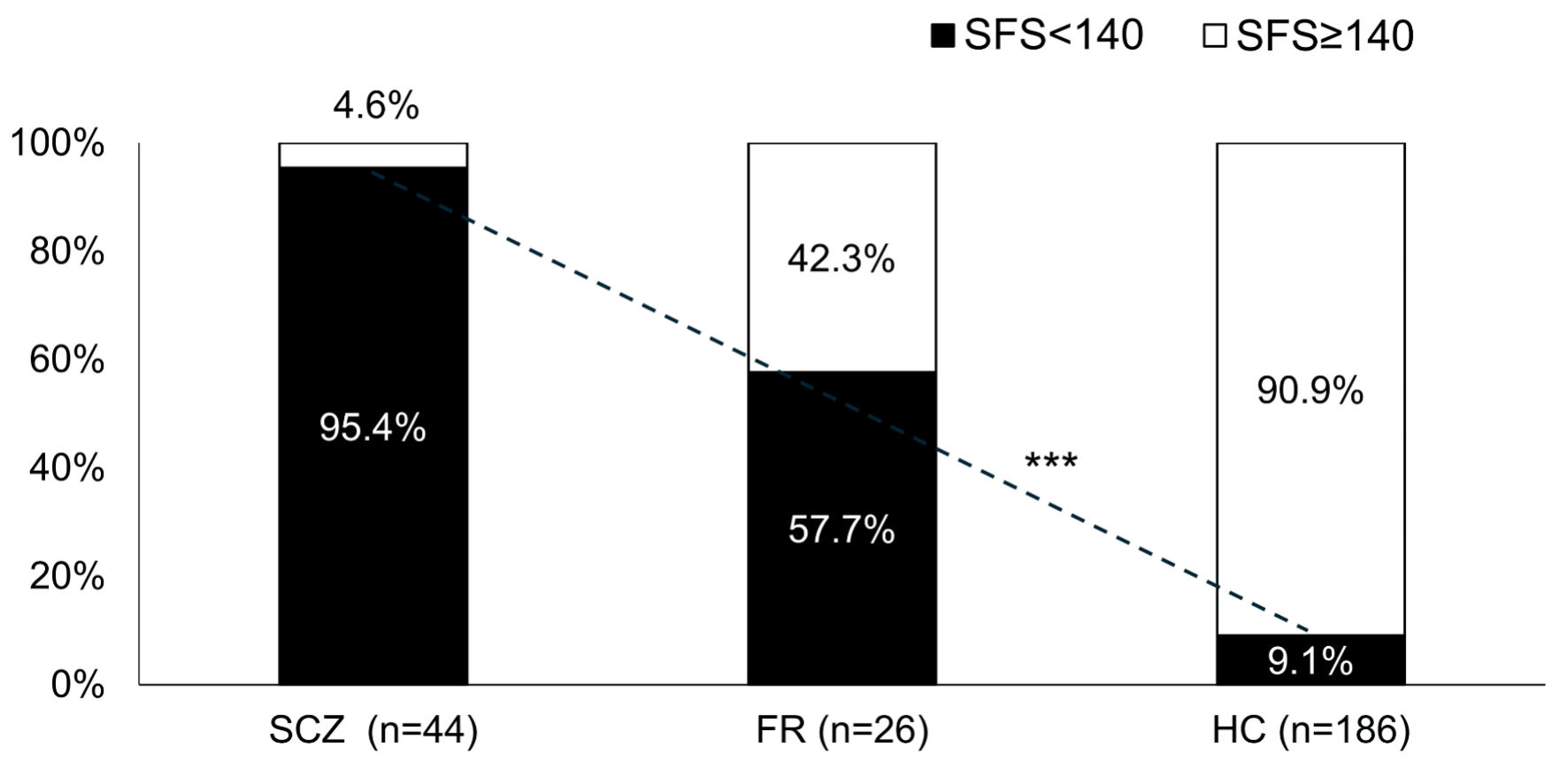

ROC curve analysis of the SFS total score for SCZ was performed (AUC 0.962) (Fig. 1). The cutoff value of the SFS total score for SCZ was 140, with a sensitivity of 0.954 and a specificity of 0.849 (Table 4). The proportion of subjects with a SFS total score < 140 was 9.1% in HC, 57.7% in FR, and 95.4% in SCZ, and there was a significant trend for the proportion of patients with SFS < 140 to increase continuously among the three groups (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for calculating the cutoff value of SFS for schizophrenia. AUC: area under the curve; SFS: Social Functioning Scale. |

Click to view | Table 4. Cutoff Value for SCZ in the SFS Total Score |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Proportion of subjects with SFS < 140 in each group. ***P < 0.0001 Cochran-Armitage test. There was a significant linear trend in the proportion of SFS < 140 among the three groups. SCZ: schizophrenia; FR: first-degree relatives; HC: healthy controls; SFS: Social Functioning Scale. |

SFS subscale by group

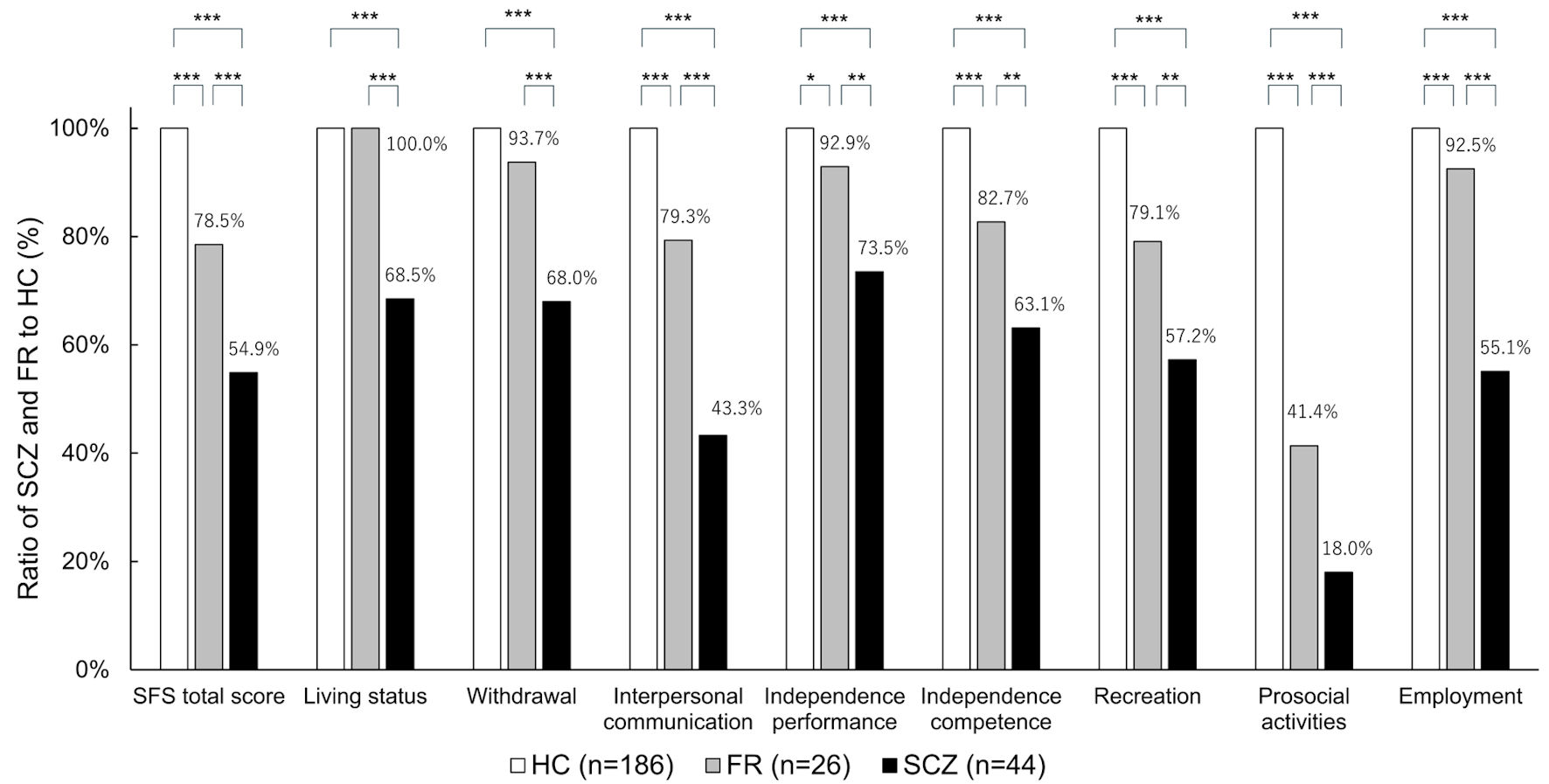

Figure 3 shows the scores of the SFS subscales for FR and SCZ, using HC as the reference. No significant differences were found between HC and FR in the living status and withdrawal; however, for all other items, scores of FR were significantly lower than those of HC, and scores of SCZ were significantly lower than those of FR.

Click for large image | Figure 3. SFS subscales for each group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. HC: healthy controls; FR: first-degree relatives; SCZ: schizophrenia; SFS: Social Functioning Scale. |

The correlation between SFS scores of patients with SCZ and their unaffected parents

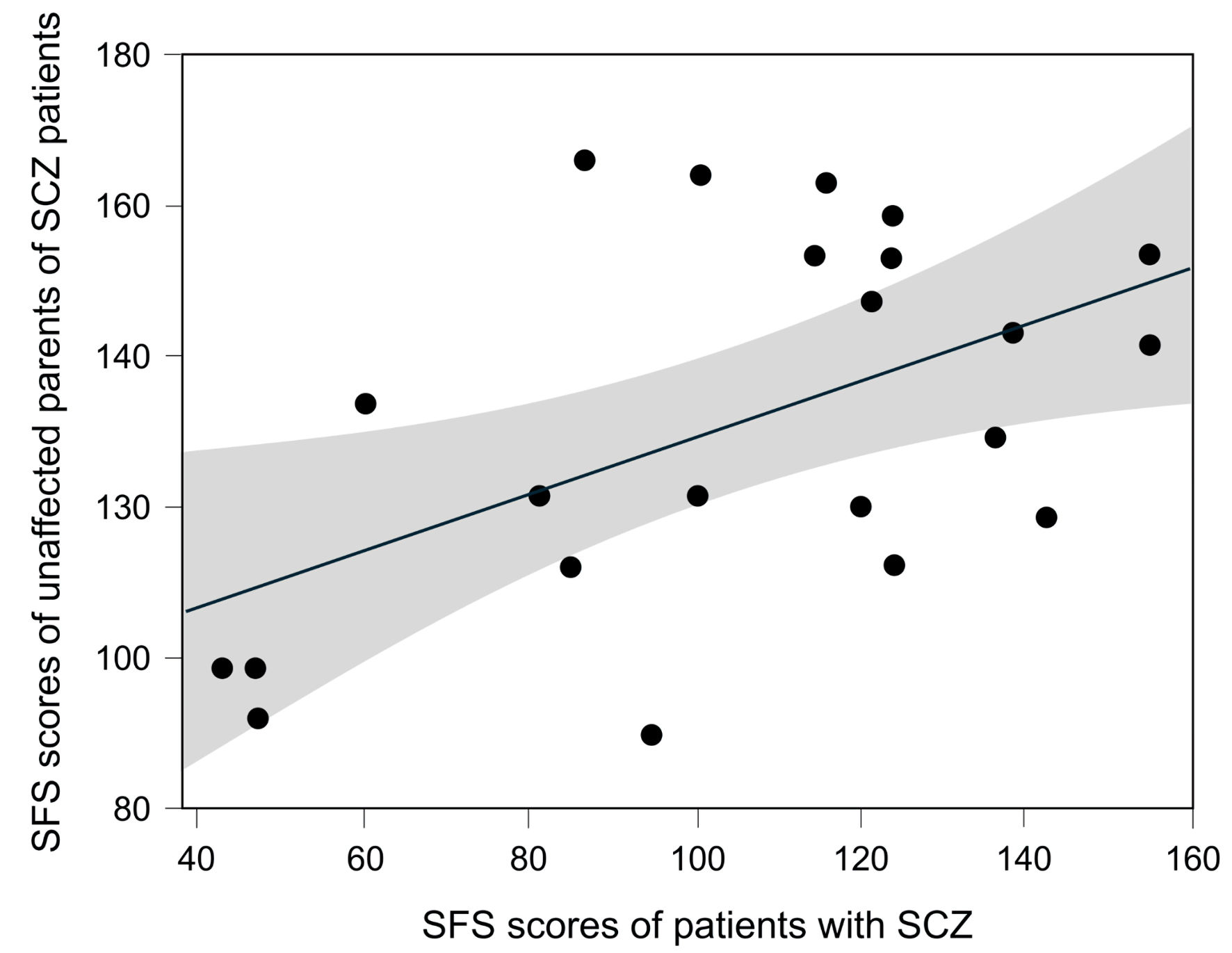

There were 22 pairs with SFS data for both the patients with SCZ and their unaffected parent. The results showed a tendency for correlation between the SFS scores of patients with SCZ and their unaffected parents, but it was not statistically significant (Spearman rank correlation coefficient: 0.3963, P = 0.0679) (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. The correlation between SFS scores of SCZ patients and their unaffected parents. A total of 22 pairs comprising patients with SCZ and their unaffected parents were included. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was 0.3963 (P = 0.0679). The gray shaded area represents the 95% confidence interval. SCZ: schizophrenia. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study, social functioning assessed by the SFS was found to be lower in FR than in HC and higher in FR than in SCZ. In addition, for all SFS sub-items, except for living status and withdrawal, the FR scores were intermediate between those of HC and SCZ. These results indicate that FR differs from HC across a broad range of social functioning domains. As mentioned above, no genetic mutations or SNPs have been identified as the etiology of SCZ; however, many genetic mutations and SNPs have been suggested to be involved [18]. The results of this study indicate that FR, who share genes with patients with SCZ, exhibit characteristics similar to those of SCZ, suggesting that various genetic factors may be involved in the pathogenesis of SCZ. Regarding FR of SCZ, it has been reported that social cognition, working memory [29], prospective memory [22], neurocognitive function [30], and executive function [31] are impaired; this study showed that social function is also impaired. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine social functioning in SCZ, FR, and HC.

On the other hand, children’s social functioning is influenced by environment during their development. It has been reported that social skills and sociability in parents and children are linked [32, 33]. Social functioning in SCZ patients can be improved through training [34], and children’s social development is influenced by parental nurturing behaviors [35]. Therefore, the SFS as an indicator of social functioning may be influenced not only by genetic factors but also by environmental factors. In this study, we evaluated the correlation of SFS scores in 22 pairs consisting of patients with SCZ and their unaffected parents. The results showed a tendency for correlation between parent and child SFS scores, but the correlation was not significant (Spearman rank correlation coefficient: 0.3963, P = 0.0679). This suggests that, although parent-child environmental factors are involved in SFS in this study, SFS cannot be explained solely by environmental factors. Therefore, regarding the results of this study, while the influence of environmental factors on SFS cannot be denied, this does not negate the possibility of genetic factors being involved.

Among the SFS subscales, the greatest discrepancy in the HC scores was observed in the prosocial activity domain. The proportion of prosocial activity scores relative to the HC was 18.0% for the SCZ group and 41.4% for the FR group. Saris et al reported that the subscale of the SFS that showed the greatest discrepancy between HC and patients with SCZ was prosocial activity [9], which is consistent with the results of our study. Prosocial activities were assessed based on the participant’s activities over the past 3 months, including going out, attending movies, theater performances, sports events, and social gatherings. Patients with SCZ are reported to engage less frequently in deep personal conversations in daily life and are more prone to interpersonal conflict [36]. Considering these factors, the decline in social functioning observed in patients with SCZ or FR may be influenced by impairments in communication skills and ability to build interpersonal relationships.

JART50 (IQ) was an influential factor on the SFS total score. Ohi et al reported that, in patients with SCZ, IQ assessed using the Short Form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-III SF) was significantly correlated with social activity assessed using the Social Activity Assessment [37]. Leeson et al also reported that IQ was a significant predictor of social functioning in patients with SCZ [38]. Improvement in IQ during the course of SCZ has been suggested to be associated with a better prognosis, and IQ may play a role in various pathophysiological aspects of SCZ [39]. The results of the present study are consistent with those of previous studies.

In our study, the length of education was associated with the SFS total score. SCZ is associated with genetic and environmental factors, and Luo et al reported that increased years of education reduce the risk of SCZ [40]. The results of the present study are consistent with those reported by Luo et al. Although this study could not fully elucidate the causal relationship between educational attainment and social functioning, previous reports have suggested that education may enhance attention, executive function [41], and cognitive function [42]. Therefore, it is possible that the indirect effects of education contributed to improvements in social functioning.

Male sex was a factor that reduced the SFS total score. In our study, the mean total length of hospitalization for patients with SCZ was 275 months for males and 176 months for females (data not shown). The decline in social functioning in men may be due to the fact that more severe cases were included among male patients.

This study has some limitations. First, social functioning in patients with SCZ is thought to be influenced by factors such as cognitive function [1], positive and negative symptoms [43, 44], and treatment-free periods [45]. However, these data were not collected for FR and HC in this study, and therefore these factors were not taken into account when assessing the impact of group on social functioning. Second, we could not exclude the possibility of some methodological selection bias in our samples. Since 88.5% of FR consisted of the parents of SCZ, the mean age in FR was increased. Third, compared with the sample size of HC, those of SCZ and FR were relatively small. Thus, false positive findings are possible. Future studies attempting to replicate our findings using larger SCZ and FR sample sizes are needed. And finally, genetic testing was not performed in this study. Elucidating the genes related to social functioning in SCZ remains a challenge for the future. These limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings.

Conclusions

In terms of social functioning as assessed by the SFS, scores for individuals with FR were intermediate between those of patients with SCZ and HC. The findings of this study indicate that there may be a potential genetic contribution to SCZ as reflected in social functioning.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (21K15737).

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

All individuals included in the study provided written informed consent.

Author Contributions

Takamitsu Shimada contributed to the conception and design for the study, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and contributed to the editing of the final manuscript. Hiroaki Kihara, Yusuke Nitta, Tatsuya Nagasawa, Mitsuru Hasegawa, Yoshiki Maeda, Yasuhiro Kawasakia and Takashi Uehara were involved in the literature review and corrections. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Any queries regarding the availability of data supporting this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

ANCOVA: analysis of covariance; AUC: area under the curve; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; FR: first-degree relatives; HC: healthy controls; IQ: intelligence quotient; JART 50: Japanese Adult Reading Test 50; QOL: quality of life; ROC: receiver operating characteristic; SCID: Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV; SCZ: schizophrenia; SFS-J: Japanese version of the Social Functioning Scale; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms

| References | ▴Top |

- Takeda T, Umehara H, Matsumoto Y, Yoshida T, Nakataki M, Numata S. Schizophrenia and cognitive dysfunction. J Med Invest. 2024;71(3.4):205-209.

doi pubmed - Jaaskelainen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, McGrath JJ, Saha S, Isohanni M, Veijola J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296-1306.

doi pubmed - Baba K, Guo W, Chen Y, Nosaka T, Kato T. Burden of schizophrenia among Japanese patients: a cross-sectional National Health and Wellness Survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):410.

doi pubmed - Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Diminic S, Stockings E, Scott JG, McGrath JJ, et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195-1203.

doi pubmed - Perala J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, Kuoppasalmi K, Isometsa E, Pirkola S, Partonen T, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):19-28.

doi pubmed - Harvey PD, Bellack AS. Toward a terminology for functional recovery in schizophrenia: is functional remission a viable concept? Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(2):300-306.

doi pubmed - Schmitt A, Falkai P. Morphological and functional alterations in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;266(1):1-2.

doi pubmed - Yasuyama T, Ohi K, Shimada T, Uehara T, Kawasaki Y. Differences in social functioning among patients with major psychiatric disorders: Interpersonal communication is impaired in patients with schizophrenia and correlates with an increase in schizotypal traits. Psychiatry Res. 2017;249:30-34.

doi pubmed - Saris IMJ, Aghajani M, Jongs N, Reus LM, van der Wee NJA, Bilderbeck AC, Winter van Rossum I, et al. Cross-disorder and disorder-specific deficits in social functioning among schizophrenia and alzheimer's disease patients. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0263769.

doi pubmed - Grant C, Addington J, Addington D, Konnert C. Social functioning in first- and multiepisode schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46(8):746-749.

doi pubmed - Gorna K, Jaracz K, Jaracz J, Kiejda J, Grabowska-Fudala B, Rybakowski J. [Social functioning and quality of life in schizophrenia patients —relationship with symptomatic remission and duration of illness]. Psychiatr Pol. 2014;48(2):277-288.

pubmed - Addington J, Penn D, Woods SW, Addington D, Perkins DO. Social functioning in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2008;99(1-3):119-124.

doi pubmed - Vassos E, Sham PC, Cai G, Deng H, Liu X, Sun X, Zhao J, et al. Correlation and familial aggregation of dimensions of psychosis in affected sibling pairs from China. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(4):305-310.

doi pubmed - Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Bjork C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, Hultman CM. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373(9659):234-239.

doi pubmed - Sullivan PF, Kendler KS, Neale MC. Schizophrenia as a complex trait: evidence from a meta-analysis of twin studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(12):1187-1192.

doi pubmed - Tsuang M. Schizophrenia: genes and environment. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(3):210-220.

doi pubmed - Cardno AG, Gottesman II. Twin studies of schizophrenia: from bow-and-arrow concordances to star wars Mx and functional genomics. Am J Med Genet. 2000;97(1):12-17.

pubmed - Ripke S, O'Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kahler AK, Akterin S, Bergen SE, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1150-1159.

doi pubmed - Chen M, Xu Z, Zhai J, Bao X, Zhang Q, Gu H, Shen Q, et al. Evidence of IQ-modulated association between ZNF804A gene polymorphism and cognitive function in schizophrenia patients. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(7):1572-1578.

doi pubmed - Walters JT, Corvin A, Owen MJ, Williams H, Dragovic M, Quinn EM, Judge R, et al. Psychosis susceptibility gene ZNF804A and cognitive performance in schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(7):692-700.

doi pubmed - Los R, Gajowiec A. Impairment of social cognition in comparative studies of patients with schizophrenia and their healthy siblings. Psychiatr Pol. 2023;57(5):967-982.

doi pubmed - Lin SZ, Wu YK, Su YA, Si TM. Prospective memory in non-psychotic first-degree relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1563-1571.

doi pubmed - Siegel C, Waldo M, Mizner G, Adler LE, Freedman R. Deficits in sensory gating in schizophrenic patients and their relatives. Evidence obtained with auditory evoked responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41(6):607-612.

doi pubmed - Earls HA, Curran T, Mittal V. A meta-analytic review of auditory event-related potential components as endophenotypes for schizophrenia: perspectives from first-degree relatives. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1504-1516.

doi pubmed - Kerr-Gaffney J, Nuerzati Y, Kopra EI, Young AH. Impulsivity in first-degree relatives at risk of psychosis and mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2024;54(13):1-9.

doi pubmed - Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake S. The Social Functioning Scale. The development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1990;157:853-859.

doi pubmed - Matsuoka K, Uno M, Kasai K, Koyama K, Kim Y. Estimation of premorbid IQ in individuals with Alzheimer's disease using Japanese ideographic script (Kanji) compound words: Japanese version of National Adult Reading Test. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;60(3):332-339.

doi pubmed - Nemoto T, Fujii C, Miura Y, Chino B, Kobayashi H, Yamazawa R, Murakami M, et al. Reliability and validity of the Social Functioning Scale Japanese version (SFS-J). Jpn Bull Soc Psychiatry. 2008;17:188-195. (in Japanese)

- Cilem Kizilpinar S, Cigdem Aydemir M, Dogan O, Bahar Atak-Akkus F, Baran Z. Social cognition and oxidative stress in schizophrenia patients and first-degree relatives of patients. Psychiatr Danub. 2023;35(4):523-534.

doi pubmed - Harave VS, Shivakumar V, Kalmady SV, Narayanaswamy JC, Varambally S, Venkatasubramanian G. Neurocognitive impairments in unaffected first-degree relatives of schizophrenia. Indian J Psychol Med. 2017;39(3):250-253.

doi pubmed - Kataoka Y, Shimada T, Koide Y, Okubo H, Uehara T, Shioiri T, Kawasaki Y, et al. Differences in executive function among patients with schizophrenia, their unaffected first-degree relatives and healthy participants. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;23(11):731-737.

doi pubmed - Burke TJ, Woszidlo A, Segrin C. The intergenerational transmission of social skills and psychosocial problems among parents and their young adult children. J Fam Commun. 2013;13:77-91.

- Okumura T, Usui E. Do parents’ social skills influence their Children’s sociability? BE J Econ Anal Policy. 2014;14:1081-1116.

- Kopelowicz A, Liberman RP, Zarate R. Recent advances in social skills training for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(Suppl 1):S12-23.

doi pubmed - Takahashi Y, Okada K, Hoshino T, Anme T. Developmental trajectories of social skills during early childhood and links to parenting practices in a Japanese sample. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135357.

doi pubmed - Weittenhiller LP, Mikhail ME, Mote J, Campellone TR, Kring AM. What gets in the way of social engagement in schizophrenia? World J Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):13-26.

doi pubmed - Ohi K, Sumiyoshi C, Fujino H, Yasuda Y, Yamamori H, Fujimoto M, Sumiyoshi T, et al. A 1.5-year longitudinal study of social activity in patients with schizophrenia. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:567.

doi pubmed - Leeson VC, Barnes TR, Hutton SB, Ron MA, Joyce EM. IQ as a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal, four-year study of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2009;107(1):55-60.

doi pubmed - Aylward E, Walker E, Bettes B. Intelligence in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of the research. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(3):430-459.

doi pubmed - Luo Y, Pang L, Zhao Y, Guo C, Zhang L, Zheng X. Gender difference in the association between education and schizophrenia in Chinese adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):296.

doi pubmed - Van der Elst W, Van Boxtel MP, Van Breukelen GJ, Jolles J. The Stroop color-word test: influence of age, sex, and education; and normative data for a large sample across the adult age range. Assessment. 2006;13(1):62-79.

doi pubmed - Lovden M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM. Education and cognitive functioning across the life span. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2020;21(1):6-41.

doi pubmed - Tominaga T, Tomotake M, Takeda T, Ueoka Y, Tanaka T, Watanabe SY, Kameoka N, et al. Relationship between social and cognitive functions in people with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2215-2224.

doi pubmed - Xie M, Yu X, Ye S, Han H, Wu R, Liu D, Hu S, et al. Cognitive function in Chinese patients with schizophrenia: the Chinese Brief Cognitive Test (C-BCT) profile of impairment. Nord J Psychiatry. 2025;79(7):537-545.

doi pubmed - Barnes TR, Leeson VC, Mutsatsa SH, Watt HC, Hutton SB, Joyce EM. Duration of untreated psychosis and social function: 1-year follow-up study of first-episode schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193(3):203-209.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, including commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.