| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 17, Number 12, December 2025, pages 688-697

Prevalence of Anxiety and Depressive Disorders Among Patients Diagnosed With Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Fahd Almalkia, e, Mohammed Zaki Abdulsattara, Faisal Khalid Rommania, Moayad Sadeq Alalia, Abdullah Hashim Saada, Yousef Mohammed Bajhzera, Abdulaziz Abdulrazzaq Makkawib, Abdullah Adil Alereinanc, Hassan Abdullah J. Alsolamid

aDepartment of Medicine, College of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

bCollege of Pharmacy, Umm AL-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

cGastroenterology and Endoscopy Department, Alnoor Specialist Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

dGastroenterology and Endoscopy Department, King Faisal Hospital, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

eCorresponding Author: Fahd M. Almalki, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, Saudi Arabia

Manuscript submitted August 29, 2025, accepted November 25, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in IBD Patients

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6372

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is linked to high risks of depression and anxiety. Stigma, limited mental health awareness, and barriers to access continue to contribute to underdiagnosis in Saudi Arabia. This study aimed to determine the prevalence of depression and anxiety among IBD patients, identify related risk factors, and assess barriers to mental health treatment.

Methods: A cross-sectional study including 92 IBD patients from gastroenterology clinics at King Faisal and Al-Noor hospitals was conducted. Data were collected through face-to-face, phone interviews, and an online Arabic questionnaire assessing sociodemographic, IBD-related factors, and mental health information using Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). Analysis employed Chi-square, Fisher’s exact, and logistic regression model to determine associations.

Results: Among 92 patients, 15.2% had symptoms of anxiety, depression, or both. Screening detected 19.6% with depressive symptoms (PHQ-2) and 46.7% with anxiety symptoms (GAD-7), with 17.4% experiencing severe anxiety symptoms. Saudi nationality (OR = 40.15, p = 0.035) was significantly linked to clinical diagnoses. Shorter disease duration (<6 months, p = 0.017; 1–3 years, p = 0.011), was associated with lower odds of anxiety symptoms, while recent exacerbations (<3 months, p = 0.012) were associated with increased risk of anxiety symptoms. Higher risk of depression symptoms was associated with recent exacerbations (OR = 7.51, p = 0.055) and smoking (OR = 5.04, p = 0.072). Barriers included stigma (8.7%), cost (6.5%), and concerns about medication side effects (40.2%).

Conclusion: The burden of undiagnosed anxiety and depression is significant among IBD patients in Makkah. Routine screening, stigma reduction, and integrated mental health care are essential.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease; Anxiety; Depression; Saudi Arabia; Mental health; Stigma

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a serious mental health condition. People with depression experience ongoing sadness, hopelessness, and a loss of interest in enjoyable activities. In addition to emotional difficulties, they may also have physical symptoms such as chronic pain or digestive problems [1]. People with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) often feel tense, restless, and irritable. They may also experience sleep problems and physical symptoms like a racing heart, dry mouth, excessive sweating, and abdominal pain [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), depression is the leading cause of disability globally, affecting an estimated 300 million people, which equates to approximately 7.5% of the world’s population [3]. Anxiety disorders represent a pervasive and burdensome group of mental health conditions that afflict a substantial segment of the global population. Data from the year 2013 indicate that one out of every nine individuals worldwide suffered from at least one form of anxiety disorder [4].

The number of newly diagnosed cases of anxiety disorders has increased significantly all over the world, from 31.13 million in 1990 to 45.82 million in 2019 over the course of the last three decades [5]. Mental health problems such as MDD and GAD are significant public health concerns in Saudi Arabia. In light of the low rates of diagnosis and treatment, the relatively high prevalence of GAD and MDD risk factors, mental health promotion, early detection, and treatment accessibility are critical in Saudi Arabia [6]. Symptoms of mental health disorders can be vague and easily missed, especially in primary care settings. People may also avoid seeking treatment due to stigma and a lack of mental health awareness. Additionally, limited access to mental health services, especially in lower-income countries, exacerbates the problem [7]. A recent large-scale screening study in Saudi Arabia found a prevalence of MDD and GAD of 11.8% and 13.8 % as measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), respectively [8].

In Saudi Arabia, several risk factors, such as female gender, low income, low educational attainment, unemployment, and long-term medical issues, have been linked to anxiety and depression. In addition, social elements, including family structure, marital status, and social support, can have a big impact on how mental health illnesses develop and persist [9]. IBD is a group of idiopathic inflammatory immune-mediated disorders of the digestive tract. It includes two main types: ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD), which differ in location of initial inflammatory reaction, continuity, and depth of involvement [10]. Epidemiological data show that inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are more common and increasing in Western countries, while the Middle East has a lower incidence [11]. Recent data show that IBD rates are rising significantly in the Middle East, likely due to the Westernization of lifestyle and diet [11]. It is believed that the factors which link anxiety, depression, and IBD include the elevation of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the two-way communication mediated by the gut-brain axis [12]. Patients with active IBD have a higher prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms. Research has shown that IBD patients are more likely to experience anxiety and depression [12]. More than 30% of IBD patients experience anxiety symptoms, while 25% exhibit signs of depression [12, 13].

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted to estimate the prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms among patients with IBD at King Faisal and Al-Noor specialist hospitals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. It also aimed to identify risk factors associated with and barriers to mental health care. The study was conducted from October 16, 2024, to August 17, 2025.

Study Setting

The research was carried out at King Faisal and Al-Noor specialist hospitals’ outpatient gastroenterology clinics, which are the secondary care hospitals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. The hospitals were selected for their high number of patients with IBD and well-established gastroenterology services, thus having a representative sample of the target population.

Study population

The study population consisted of patients with IBD (UC or CD) who presented to the gastroenterology clinics at the aforementioned hospitals.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were IBD patients older than 18 years who consented to participate in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion was rendered to those with a recent exacerbation of IBD (within the past month) to avoid confounding acute disease activity with reactive psychiatric symptoms and drug-induced reactions.

Sample size and sampling technique

Convenience sampling was employed, and 92 eligible IBD patients were enrolled during the study period. The required sample size was determined from earlier estimates of the prevalence of depression and anxiety in IBD patients (approximately 25-30%) [13], with an a priori target confidence level of 95% and an acceptable margin of error of 10%, adjusted for the size of the clinic population.

Data collection and management

Data were collected between January 2025 and July 2025 using a formal Arabic-language questionnaire filled in through face-to-face, phone interviews, and/or an online electronic Google Form to ensure optimal accessibility. The questionnaire had five sections: 1) Informed consent: participants provided signed or electronic consent to ensure voluntary participation and confidentiality. 2) Sociodemographic data: age, gender, nationality, level of education, and smoking status. 3) IBD characteristics: disease phenotype (UC or CD), duration, activity status, history of recent flare, prior treatment (steroids, biologics), and surgery. 4) Psychiatric assessment: symptom frequency of depression and anxiety using validated Arabic language versions of the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) depression screening instrument [14] and GAD-7 scale to measure the severity of GAD [15]. 5) Barriers to care: stigma, cost, and concern about medication side effects.

Ethical statements

Ethical approval was obtained from Umm al-Qura University and the Institutional Review Boards of King Faisal and Al-Noor specialist hospitals. This study was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards of the responsible institution on human subjects, as well as with the Helsinki Declaration. The information was securely stored following international human research ethics standards and local laws.

Statistical analysis and variables

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Quantitative data defining sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or medians (range) according to the normality of distribution, and categorical data as frequencies and percentages. Correlation between categorical variables (e.g., treatment, diagnosis, sex, and barriers) was calculated using Chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact tests where cell counts were small. Binary logistic regression also identified independent predictors of clinical diagnosis and PHQ-2 positivity, whereas the binary logistic regression model assessed predictors of any level of anxiety compared to no anxiety (based on GAD-7). Independent variables were age, sex, nationality, education, smoking status, disease phenotype, duration, activity, flare-up history, and factors related to treatment. For all analyses, a P-value less than 0.05 was deemed statistically significant with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

| Results | ▴Top |

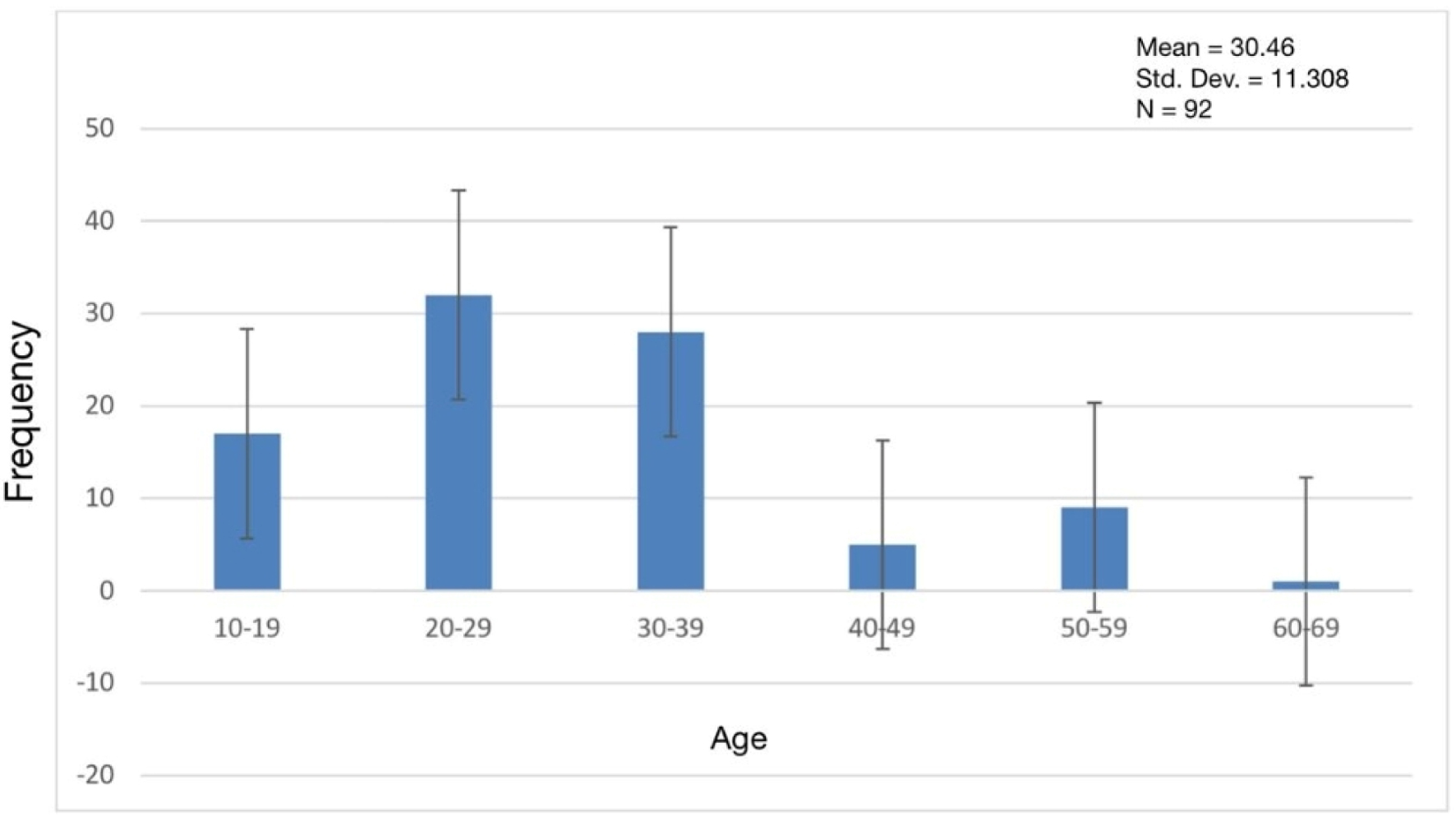

A total of 92 patients with IBD completed the survey. The majority of participants were male (60.9%) and of Saudi nationality (90.2%), while a smaller proportion were smokers (19.6%) (Table 1). Figure 1 displays the age distribution of the 92 participants. The sample had a mean age of 30.46 years (SD = 11.31).

Click to view | Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants (n = 92) |

Click for large image | Figure 1. Distribution of participants’ age. |

Table 2 details the clinical characteristics of the participants. UC was the more common diagnosis (72.8%) compared to CD (27.2%). Furthermore, 47.8% of patients had active diseases, and 65.2% were receiving steroid therapy.

Click to view | Table 2. Clinical Characteristics |

As shown in Table 3, only 15.2% of participants reported having been clinically diagnosed with anxiety or depression. Among all patients, just 13% had received psychiatric treatment, and 14.1% were currently taking psychiatric medications. This suggests that many patients experiencing psychological symptoms remain undiagnosed or untreated.

Click to view | Table 3. Prevalence of Psychiatric Diagnosis and Treatment Use |

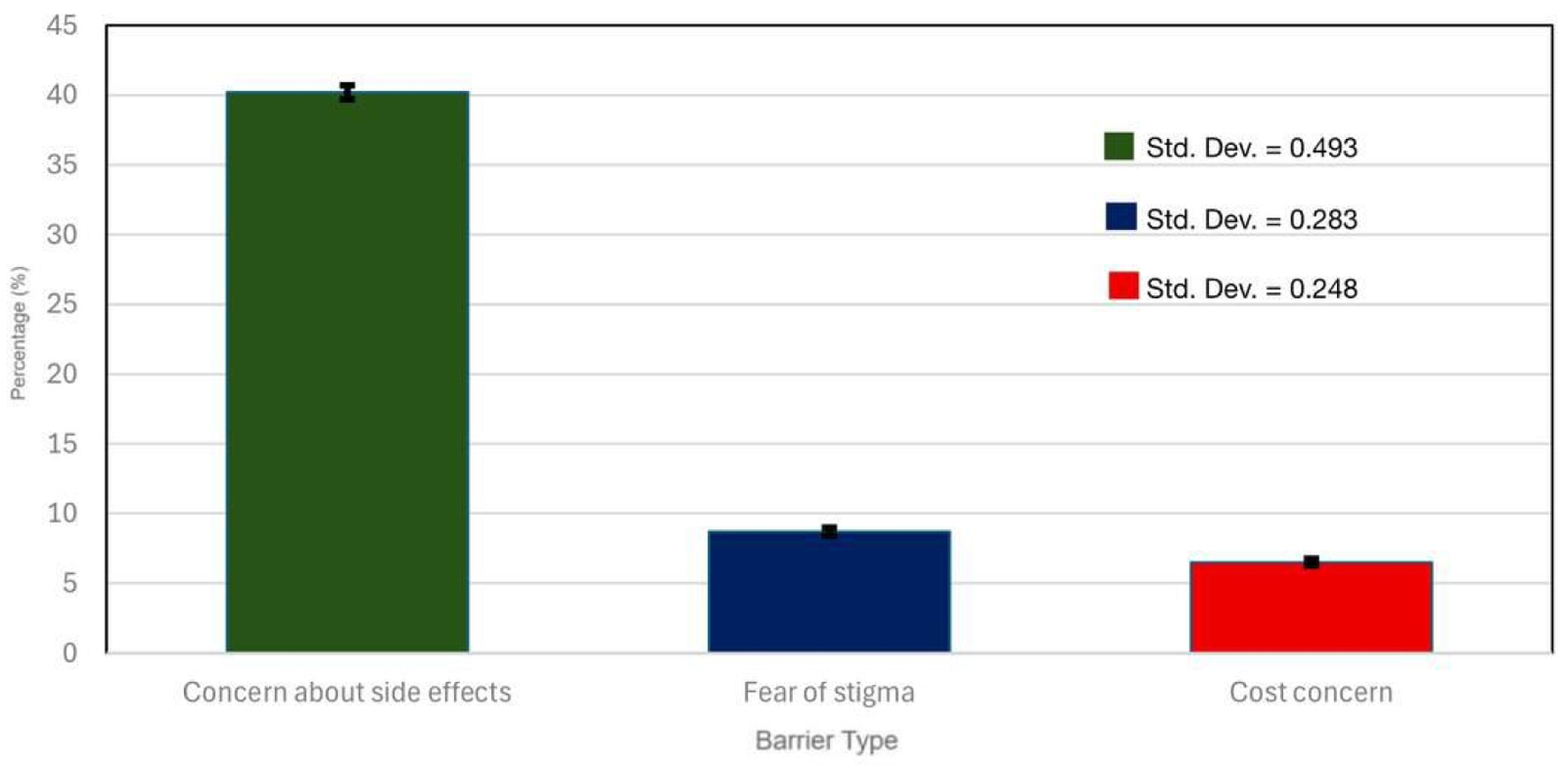

Among the IBD patients surveyed, 8.7% reported avoiding psychiatric help due to fear of stigma, while 6.5% cited cost concerns. A notably larger proportion (40.2%) expressed concern about the potential side effects of psychiatric medications. These findings suggest that although stigma and cost are relatively infrequent concerns, medication-related worries are common and may serve as a substantial barrier to care, as can be seen in Figure 2 and Supplementary Material 1 (jocmr.elmerjournals.com).

Click for large image | Figure 2. Barriers to mental health treatment among IBC patients. The most significant barrier to mental health treatment was concern about medication side effects (40.2%), followed by fear of stigma (8.7%) and cost concerns (6.5%) (n = 92). IBD: inflammatory bowel disease. |

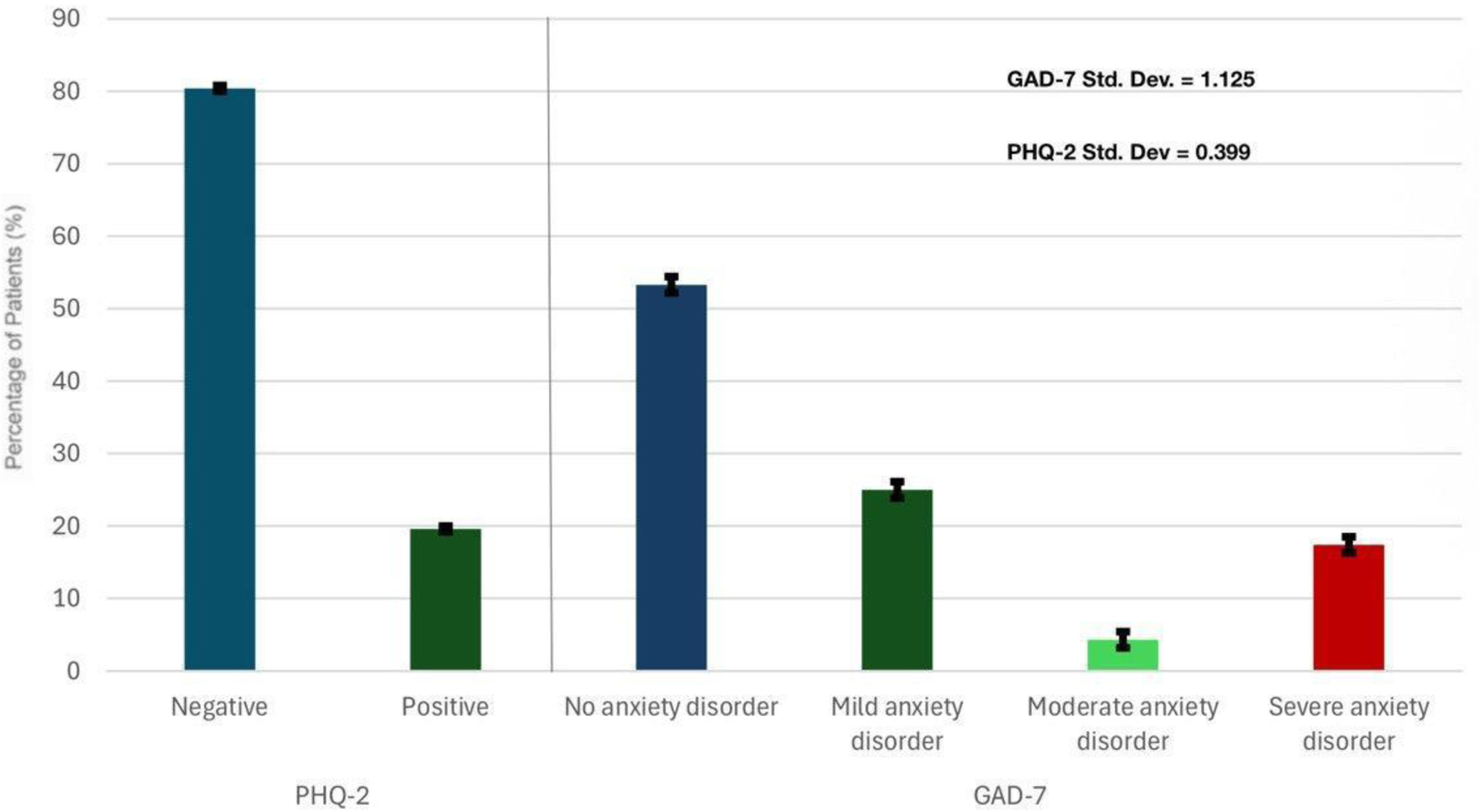

Screening for depressive symptoms with the PHQ-2 was positive for 19.6% of patients. Regarding anxiety, GAD-7 screening revealed that 46.7% of patients experienced some level of anxiety, with 17.4% having severe symptoms, as can be seen in Figure 3 and Supplementary Material 2 (jocmr.elmerjournals.com).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Clustered screening results for depression and anxiety categories among 92 IBD patients. Of the IBD patients screened, 19.6% screened positive for depressive symptoms using the PHQ-2, while 46.7% reported anxiety symptoms using the GAD-7, with 17.4% experiencing severe anxiety. GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; PHQ-2: Patient Health Questionnaire-2. |

There is a significant association between clinical diagnosis and psychiatric treatment (Fisher’s exact test, P < 0.001). More than half of the diagnosed patients (57.1%) received treatment, while only 5.1% of undiagnosed patients did. This suggests that many symptomatic patients remain untreated unless they are formally diagnosed, as can be seen in Figure 4 and Supplementary Material 3 (jocmr.elmerjournals.com).

Click for large image | Figure 4. Relationship between clinical diagnosis and psychiatric treatment use among IBD patients. Among the study participants, a large majority of those who had not been diagnosed with anxiety or depression (95.4%) had also received psychiatric treatment, whereas more than half of those who had a clinical diagnosis (57.7%) had received psychiatric treatment. IBD: inflammatory bowel disease. |

A multivariable model shows that nationality has a statistically significant association with clinical diagnosis (P = 0.035); the estimate was unstable, with a very wide CI indicating possible model overfitting related to the small number of non-Saudi participants. Other variables, such as sex and smoking, showed elevated odds but did not reach statistical significance (Table 4).

Click to view | Table 4. Multivariable Logistic Regression: Predictors of Clinical Diagnosis of Anxiety or Depression |

The logistic regression analysis, detailed in Table 5, did not identify any statistically significant predictors for a positive depression screen (P < 0.05). However, two variables approached this threshold: patients with a recent disease flare-up had over seven times the odds of screening positive (OR = 7.51, 95% CI = 0.96 - 58.81, P = 0.055), and smokers had five times the odds (OR = 5.04, 95% CI = 0.87 - 29.38, P = 0.072). Although not statistically significant, these findings suggest that recent disease activity and smoking may be clinically relevant factors for identifying patients at risk of depression.

Click to view | Table 5. Logistic Regression: Predictors of Positive PHQ-2 Screening for Depression |

Table 6 presents the binary logistic regression model assessing predictors of any level of anxiety compared to no anxiety (based on GAD-7).

Click to view | Table 6. Binary Logistic Regression: Any Level of Anxiety Compared to No Anxiety (Based on GAD-7) |

Shorter disease durations were significantly associated with lower odds of anxiety. Participants with a disease duration of less than 6 months had lower odds of anxiety (OR = 0.024, 95% CI = 0.001 - 0.508, P = 0.017). Likewise, those with disease durations of 6 months to 1 year (OR = 0.120, 95% CI = 0.015 - 0.932, P = 0.043) and 1 to 3 years (OR = 0.089, 95% CI = 0.014 - 0.580, P = 0.011) also showed significantly reduced odds compared with patients who had the disease for more than 5 years.

Although a recent flare-up within the past 3 months showed a strong and significant association with anxiety (OR = 17.42), the wide CI indicates some uncertainty in the estimate, likely due to the relatively small sample size.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

In this study of 92 patients with IBD seen and followed at two secondary hospitals in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, 15.2% reported a previous clinical diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression. When compared with extensive population-based studies, these rates are lower than those reported internationally. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis that included 77 studies, the authors found a prevalence of anxiety symptoms in 32.1% of patients with IBD compared with 10.4% of the background population in 58 studies, and depression was diagnosed in 25.2% with IBD compared with 17.9% in non-IBD controls in 75 studies. This is substantially higher than the prevalence observed in our study. Furthermore, a Danish cohort study found that anxiety and depression risks were elevated both before and after IBD diagnosis, with the highest risk observed around the time of diagnosis [15]. Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of unselected cohorts estimated a 1.48-fold increased risk of anxiety and 1.55-fold increased risk of depression following IBD diagnosis [16]. In Saudi Arabia, a study conducted at King Fahad Specialist Hospital in Qassim reported a prevalence of anxiety symptoms at 17.3% and depressive symptoms at 19.6% among IBD patients [17]. Using validated screening tools, we found that 19.6% screened positive for depression on the PHQ-2, and 46.7% reported at least mild anxiety symptoms on the GAD-7. These rates are consistent with the pooled prevalence estimates from global meta-analyses, which report anxiety symptoms in approximately 32% and depression symptoms in 25% of IBD patients [12]. However, they are higher for anxiety compared to the Qassim study (17.3%) [17]. These figures are comparable to our PHQ-2 depression positivity rate, but lower than our GAD-7 anxiety detected cases, likely due to methodological differences, including the use of symptom thresholds, sample characteristics, cultural perception of stress and anxiety, and inclusion of even mild anxiety cases in our analysis. The lower rates of depression in our cohort may reflect underdiagnosis, and cultural differences in reporting psychiatric depressive symptoms, or differences in healthcare access and utilization, stigma toward mental health conditions, limited awareness, and potential under-screening in gastroenterology clinics could further contribute to this disparity.

We identified several factors associated with anxiety and depression outcomes. Nationality was significantly related to clinical diagnosis, with a very high OR and a wide CI. This likely reflects statistical instability rather than a true effect due to the small number of non-Saudi participants. Crohn’s phenotype and shorter disease duration were associated with higher odds of anxiety severity, and recent flare-ups were linked to higher PHQ-2 positivity. In the recent meta-analysis, patients with CD were 20% more likely than those with UC to report anxiety and depression [12]. The prevalence of anxiety and depression was higher in people with active IBD than in those with dormant disease [18]. In a more recent publication, both diagnoses (CD and UC) were associated with higher odds of depression and anxiety [12].

The Danish cohort study and the bidirectional meta-analysis support the idea that psychiatric symptoms and IBD are mutually reinforcing, possibly via inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and microbiome-mediated mechanisms [18]. The study revealed that a shorter disease duration is linked with greater anxiety, which may reflect the psychological impact of adapting to a new chronic illness and uncertainty about disease prognosis. Furthermore, the analysis indicated that co-existing depression or anxiety increased the risk of IBD relapse [19]. Psychological stress might fuel and contribute to gut inflammation, and thus stress management could serve as a valuable component of IBD care [20]. The study showed that mental health affected the management of IBD. Depression negatively influenced the remission rate after receiving anti-TNF-alpha, and was associated with a worse outcome for patients on steroids [21]. Notably, anxiety and depression were worse in patients who were not on immune modulators, and effective treatment of IBD may improve mental health [22]. Two systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirmed that antidepressant treatment was associated with significant improvement in somatic and psychological symptoms as well as reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms/scores [23, 24]. The presence of depression and anxiety may adversely impact the management of IBD due to the interconnection between psychological stress and gut inflammation. Addressing mental health symptoms should therefore be a key component of patient care [21]. Despite the high prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms, few participants had used psychiatric treatment. Barriers included fear of stigma (8.7%), cost concerns (6.5%), and concern about medication side effects (40.2%). None were significantly associated with gender. A report in the general population of Saudi Arabia indicates that stigma is the most common barrier, 40% [25]. The observed low prevalence of anxiety and depression symptoms in our cohort may be attributed to the high level of stigma, which could lead individuals to underreport symptoms or perceive them as insignificant. These findings emphasize the need for targeted interventions to reduce stigma, enhance patient education about psychiatric treatments, and integrate mental health services into routine IBD care. The impact of diet on IBD and its associated depression and anxiety symptoms has been extensively investigated. For instance, research indicates a specific association between adherence to a Mediterranean diet and a reduced risk of depression [26]. On a functional level, dietary polyphenols have been shown to ameliorate IBD by modulating gut microbiota, reducing inflammation, and enhancing gut barrier integrity, indicating their potential as a nutritional therapeutic strategy [27]. Conversely, a high dietary intake of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), including Nε-(carboxymethyl)lysine and MG-H1, is associated with an increased risk of depression and anxiety, a relationship potentially moderated by genetic factors and advanced lipid peroxidation [28]. While the impact of non-IBD-specific psychosocial stressors, such as financial difficulties, social support, and occupational characteristics, on depression and anxiety in this patient population remains understudied, evidence from related research confirms their potential significance. For instance, financial hardships have demonstrated a marked association with depressive and anxiety symptoms, with a consistently stronger relationship to depression [29]. Conversely, strong social support from family and friends has been identified as a protective factor, linked to lower levels of these symptoms [30]. Furthermore, specific adverse occupational characteristics are significant risk factors for the incidence of anxiety and depressive disorders [31].

Implication

Given the psychological burden associated with IBD, patients should be screened for depression and anxiety at baseline and at least annually. As recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology, those who screen positive should be referred for appropriate mental health support [32].

Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include its two-center design, inclusion of both clinical diagnosis and screening tool outcomes, use of validated Arabic versions of PHQ-2 and GAD-7, and the novel exploration of treatment barriers in a Saudi IBD population. However, limitations must be acknowledged. Data on psychiatric diagnoses were self-reported without verification from medical records, introducing potential recall and reporting bias. The PHQ-2 and GAD-7 are screening instruments, not diagnostic tools, which may result in misclassification. Additionally, the hospital-based sample limits generalizability to the broader Saudi IBD population, particularly those managed in primary care or not engaged in regular medical follow-up. Additionally, we did not ask about the diagnoses of anxiety and depression separately; both conditions were addressed in a single combined question, which may have limited the precision of our prevalence estimates. The stigma question was assessed using a simple yes/no format, which does not capture the complexity, granularity, or degree of stigma experienced; future studies should explore this issue using more detailed and validated stigma assessment tools. Other potentially relevant factors that may contribute to anxiety and depression in IBD patients were not included in our questionnaire, limiting the scope of our analysis. Finally, the majority of our participants were Saudi nationals, and most were diagnosed with UC, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to more diverse IBD populations. Furthermore, the relatively small sample size (n = 92) limited statistical power, potentially explaining why some variables showed borderline P-values. Generalizability is also constrained by the sampling method; the convenience sample was drawn from only two tertiary hospitals in Makkah, and the cohort’s homogeneity (predominantly Saudi with UC) limits the exploration of cultural or phenotypic diversity. Methodologically, reliance on self-reported diagnoses, unverified by medical records, introduces a significant risk of recall and reporting bias, especially given the context of stigma. This is compounded by the use of a combined “anxiety or depression” question, preventing the independent assessment of each disorder, and an oversimplified yes/no stigma measure that fails to capture the construct’s complexity. Finally, the study did not measure key confounders strongly linked to mood disorders, such as pain, fatigue, and social support.

The logistic regression model may have been affected by overfitting due to the small number of non-Saudi participants and limited cases with a clinical diagnosis. This may have resulted in unstable or inflated odds ratios, particularly for nationality-related associations.

The small sample size within key subgroups, such as patients with recent flare-ups, limited the precision of regression estimates and contributed to wide CIs. Finally, the study’s cross-sectional design prevents the determination of a temporal relationship between psychological symptoms and disease activity; therefore, causality cannot be established.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that while the prevalence of clinically diagnosed anxiety and depression in IBD patients in Makkah is lower than in many international cohorts, nearly one in five screened positive for depression, and almost half experienced anxiety symptoms. Key associated factors included nationality, Crohn’s phenotype, shorter disease duration, and recent flare-ups. Barriers to care - especially concerns about medication side effects - likely contribute to the treatment gap. These findings underscore the need for routine mental health screening in IBD clinics, culturally tailored psychoeducation, and integrated gastroenterology-psychiatry services to address both the physical and psychological needs of patients.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Distribution of stigma and access barriers to mental health treatment.

Suppl 2. Screening results for depression and anxiety using PHQ-2 and GAD-7.

Suppl 3. Crosstab between clinical diagnosis and psychiatric treatment use.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who have given their consent, time, and responded to the questionnaire.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

All participants provided informed consent, which included details about the study purpose, voluntariness, and confidentiality protocols. Participants were free to withdraw at any time.

Author Contributions

Fahd Almalki (guarantor): study design, preparation of the manuscript, data analysis/question/acquisition, discussion, literature search, and manuscript review; Mohammed Z. Abdulsattar, Faisal K. Rommani, Moayad S. Alali, and Abdullah H. Saad: preparation and editing of the manuscript, data analysis/questions/acquisition, statistical analysis, and manuscript review. Abdulaziz A. Makkawi, Abdullah A. Alereinan, Hassan Abdullah J. Alsolami, and Yousef M. Bajhzer: preparation of the manuscript, data questions/acquisition, and manuscript review.

Data Availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

| References | ▴Top |

- HealthCentral. Depression symptoms: emotional and physical warning signs [Internet]. HealthCentral; 2022 [cited Aug 18, 2025]. Available from: https://www.healthcentral.com/condition/depression-symptoms.

- Tyrer P, Baldwin D. Generalised anxiety disorder. Lancet. 2006;368(9553):2156-2166.

doi pubmed - World Health Organization. Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017 [cited Aug 20, 2025]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/254610/WHO-MSD-MER-2017.2-eng.pdf.

- Craske MG, Stein MB. Anxiety. Lancet. 2016;388(10063):3048-3059.

doi pubmed - Yang X, Fang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yin X, Man J, Yang L, et al. Global, regional and national burden of anxiety disorders from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2021;30:e36.

doi pubmed - Alhabeeb AA, Al-Duraihem RA, Alasmary S, Alkhamaali Z, Althumiri NA, BinDhim NF. National screening for anxiety and depression in Saudi Arabia 2022. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1213851.

doi pubmed - Qureshi NA, Al-Habeeb AA, Koenig HG. Mental health system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1121-1135.

doi pubmed - BinDhim NF, Althumiri NA, Basyouni MH, Alageel AA, Alghnam S, Al-Qunaibet AM, Almubarak RA, et al. Saudi Arabia Mental Health Surveillance System (MHSS): mental health trends amid COVID-19 and comparison with pre-COVID-19 trends. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):1875642.

doi pubmed - Al-Qadhi W, Ur Rahman S, Ferwana MS, Abdulmajeed IA. Adult depression screening in Saudi primary care: prevalence, instrument and cost. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:190.

doi pubmed - Xia B, Crusius J, Meuwissen S, Pe?a A. Inflammatory bowel disease: definition, epidemiology, etiologic aspects, and immunogenetic studies. World J Gastroenterol. 1998;4(5):446-458.

doi pubmed - Mosli M, Alawadhi S, Hasan F, Abou Rached A, Sanai F, Danese S. Incidence, prevalence, and clinical epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Arab world: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2021;6(3):123-131.

doi pubmed - Barberio B, Zamani M, Black CJ, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(5):359-370.

doi pubmed - Mikocka-Walus A, Knowles SR, Keefer L, Graff L. Controversies revisited: a systematic review of the comorbidity of depression and anxiety with inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(3):752-762.

doi pubmed - Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284-1292.

doi pubmed - Bisgaard TH, Poulsen G, Allin KH, Keefer L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Jess T. Longitudinal trajectories of anxiety, depression, and bipolar disorder in inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;59:101986.

doi pubmed - Umar N, King D, Chandan JS, Bhala N, Nirantharakumar K, Adderley N, Zemedikun DT, et al. The association between inflammatory bowel disease and mental ill health: a retrospective cohort study using data from UK primary care. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(5):814-822.

doi pubmed - Alharbi M, Alhumaid A, Almutairi S, Alotaibi M. Anxiety and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease at King Fahad Specialist Hospital, Qassim region. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e44126.

doi - Bisgaard TH, Allin KH, Elmahdi R, Jess T. The bidirectional risk of inflammatory bowel disease and anxiety or depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2023;83:109-116.

doi pubmed - Mittermaier C, Dejaco C, Waldhoer T, Oefferlbauer-Ernst A, Miehsler W, Beier M, Tillinger W, et al. Impact of depressive mood on relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective 18-month follow-up study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(1):79-84.

doi pubmed - Schneider KM, Blank N, Alvarez Y, Thum K, Lundgren P, Litichevskiy L, Sleeman M, et al. The enteric nervous system relays psychological stress to intestinal inflammation. Cell. 2023;186(13):2823-2838.e2820.

doi pubmed - Persoons P, Vermeire S, Demyttenaere K, Fischler B, Vandenberghe J, Van Oudenhove L, Pierik M, et al. The impact of major depressive disorder on the short- and long-term outcome of Crohn's disease treatment with infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(2):101-110.

doi pubmed - Calvet X, Gallardo O, Coronas R, Casellas F, Montserrat A, Torrejon A, Vergara M, et al. Remission on thiopurinic immunomodulators normalizes quality of life and psychological status in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12(8):692-696.

doi pubmed - Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, Wilson IG, Andrews JM, Holtmann GJ. Antidepressants and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:24.

doi pubmed - Weston F, Carter B, Powell N, Young AH, Moulton CD. Antidepressant treatment in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;36(7):850-860.

doi pubmed - Mohamed AA, Alomair SM, Alnijadi AA, Abd Aziz F, Almulhim AS, Hammad MA, Emeka PM. Barriers to mental illness treatment in Saudi Arabia: a population-based cross-sectional study. Cureus. 2024;16(2):e53797.

doi pubmed - Eliby D, Simpson CA, Lawrence AS, Schwartz OS, Haslam N, Simmons JG. Associations between diet quality and anxiety and depressive disorders: A systematic review. J Affect Disord Rep. 2023;14:100629.

doi - Jiang K, Bai Y, Hou R, Chen G, Liu L, Ciftci ON, Farag MA, et al. Advances in dietary polyphenols: Regulation of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) via bile acid metabolism and the gut-brain axis. Food Chem. 2025;472:142932.

doi pubmed - Zhang Y, He H, Hao R, Jiang F, Li X, Ma Z, Qin LQ, et al. Associations of dietary advanced glycation end products and the risk of depression and anxiety. Eur J Nutr. 2025;64(7):296.

doi pubmed - Bjorndal LD, Roysamb E, Nes RB, von Soest T, Ebrahimi OV. Financial factors and depression and anxiety: a symptom-specific approach in the general population. SSM Ment Health. 2025;8:100508.

- Fitzpatrick MM, Anderson AM, Browning C, Ford JL. Relationship between family and friend support and psychological distress in adolescents. J Pediatr Health Care. 2024;38(6):804-811.

doi pubmed - Gan YH, Deng YT, Yang L, Zhang W, Kuo K, Zhang YR, He XY, et al. Occupational characteristics and incident anxiety and depression: A prospective cohort study of 206,790 participants. J Affect Disord. 2023;329:149-156.

doi pubmed - Farraye FA, Melmed GY, Lichtenstein GR, Barnes EL, Limketkai BN, Caldera F, Kane S. ACG clinical guideline update: preventive care in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025;120(7):1447-1473.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.