| Journal of Clinical Medicine Research, ISSN 1918-3003 print, 1918-3011 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Clin Med Res and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://jocmr.elmerjournals.com |

Original Article

Volume 17, Number 12, December 2025, pages 716-725

Atrial Fibrillation in the Context of Thyrotoxicosis: Prevalence and Clinical Determinants

Sukrisd Koowattanatianchaia, Arwarit Pocathikorna, Vimonsri Rangsrisaeneepitakb, Kiraphol Kaladeec, Chatchai Kreepalad, e

aDivision of Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Burapha University, Chonburi, Thailand

bDivision of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, Burapha University, Chonburi, Thailand

cSchool of Health Science, Sukhothai Thammathirat Open University, Nonthaburi, Thailand

dNephrology Unit, School of Internal Medicine, Institute of Medicine, Suranaree University of Technology, Nakhon Ratchasima, Thailand

eCorresponding Author: Chatchai Kreepala, Nephrology Unit, School of Internal Medicine, Institute of Medicine, Suranaree University of Technology, Nakhon Ratchasima 30000, Thailand

Manuscript submitted October 3, 2025, accepted December 1, 2025, published online December 24, 2025

Short title: AF in Thyrotoxicosis: Prevalence and Determinants

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr6413

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a frequent but variably reported complication of thyrotoxicosis, with mechanisms that extend beyond thyroid hormone excess. Clarifying its prevalence and determinants may guide early detection and management.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study of adults with thyrotoxicosis. Clinical, biochemical, and electrocardiographic data were reviewed. Associations between variables and AF were assessed using generalized linear models with robust errors, and results expressed as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Results: Among 801 patients with thyrotoxicosis, 65 had AF, yielding a prevalence of 8.1% (95% CI: 6.3 - 10.2). Compared with non-AF patients, those with AF were older, more often male (48% vs. 20%), and more frequently had chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, diabetes, heart failure (HF), cerebrovascular disease, and thyroid crisis (all P < 0.01). In multivariable analysis, independent determinants included age 35 - 60 years (adjusted OR 5.48; 95% CI: 2.03 - 14.83), age > 60 years (adjusted OR 11.39; 95% CI: 3.43 - 37.76), male sex (adjusted OR 3.38; 95% CI: 1.70 - 6.30), HF (adjusted OR 11.25; 95% CI: 2.85 - 44.54), and thyroid crisis (adjusted OR 61.84; 95% CI: 21.89 - 181.32). Thyroid hormone levels were not independently associated with AF.

Conclusion: AF was observed in approximately 8% of patients with thyrotoxicosis. The findings suggested that clinical vulnerabilities - older age, male sex, HF, and thyroid crisis - were more strongly associated with AF than thyroid hormone levels. These results supported targeted AF screening in high-risk thyrotoxic patients and indicated that rhythm management should consider patient susceptibility alongside restoring euthyroidism.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation; Thyrotoxicosis; Hyperthyroidism; Risk factors; Prevalence

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia worldwide, contributing substantially to morbidity and mortality through heart failure (HF) and thromboembolic complications [1-3]. Its risk factors are diverse, including advancing age, hypertension, diabetes, structural heart disease, and endocrine disorders, among which thyrotoxicosis has long been recognized as a precipitating condition [2, 3].

The association between thyrotoxicosis and AF, however, is complex and not universal. Not all patients with thyrotoxicosis develop AF. Clinical severity, such as marked hormone excess, thyroid crisis, or long-term exposure, may increase arrhythmic risk through sympathetic activation and atrial electrical remodeling, yet evidence for direct causality remains inconclusive [3-5]. Similarly, when AF is observed in the context of thyrotoxicosis, it cannot be assumed that thyroid dysfunction is the sole trigger. Other risk factors, such as male sex, older age, HF, and concomitant cardiovascular comorbidities, often contribute [4, 6].

Another key issue concerns reversibility. Restoration of euthyroidism may promote reversion to sinus rhythm in some patients, but AF persists in many others, suggesting the presence of irreversible structural or electrical substrates that are independent of thyroid hormone status [7-9]. From a healthcare perspective, prolonged hospitalization in thyrotoxic patients with AF also carries substantial resource and cost implications, underscoring the importance of early recognition and targeted management strategies [10]. At a biological level, AF in thyrotoxicosis likely reflects not only hemodynamic changes but also complex molecular involvement, reminiscent of broader concepts of tissue injury and repair observed in other organ systems [11].

Epidemiological studies have reported a prevalence of AF in thyrotoxicosis ranging from 5% to 15%, higher than in the general population [1, 12-14]. In this study, we observed a prevalence of approximately 8%, with significant associations identified for male sex, older age, higher body mass index, HF, and thyroid crisis. Importantly, these associations should be interpreted as correlations rather than direct causality.

The objective of this study was to clarify the prevalence and clinical determinants of AF in patients with thyrotoxicosis, with a particular emphasis on identifying overlapping, potentially modifiable factors that may enhance rhythm recovery. This approach highlights that while the link between thyrotoxicosis and AF appears straightforward, there remain important knowledge gaps with significant clinical implications.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

Study design and setting

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted at Burapha University Hospital, Chonburi Province, Thailand, a regional tertiary medical center. Medical records were reviewed for all patients diagnosed between April 1, 2019, and April 1, 2024.

Ethical approval and participants

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Burapha University (approval no. HS091/2567), and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Eligible participants were adults aged ≥ 18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, defined according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10 code: E05). Patients were excluded if they 1) had received amiodarone prior to the diagnosis of thyrotoxicosis, because the medication can independently alter thyroid hormone levels and atrial electrophysiology (e.g., suppression of AF episodes or induction of amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis), making it difficult to attribute AF directly to the thyrotoxic state, or 2) had incomplete clinical records. All eligible patients during the study period were included.

Sample size calculation

The minimum required sample size was calculated using the formula for simple logistic regression with a binary independent variable. Based on hospital records, approximately 1,160 patients with thyrotoxicosis were treated between 2019 and 2024. Literature review indicated that the prevalence of AF among thyrotoxic patients ranges from 5% to 15%; a prevalence of 7% was used for estimation [1, 15, 16]. With a 95% confidence level (Z = 1.96), α = 0.05, and error (d) = 0.01, the required sample size was 793 patients.

Data collection

Data were extracted from hospital medical records. Collected variables included: 1) Demographic and baseline clinical data: age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI), blood pressure, heart rate, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, ischemic heart disease, chronic kidney disease (CKD)), smoking and alcohol consumption, and admission status (inpatient vs. outpatient). 2) Thyrotoxicosis-related data: date and age at diagnosis, presenting symptoms (palpitation, tremor, irritability, heat intolerance, sweating, goiter, eye signs such as exophthalmos, lid lag, lid retraction), presence of thyroid crisis, etiology (Graves’ disease, toxic adenoma, multinodular goiter, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)-secreting adenoma, drug-induced), and treatments received (antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine ablation, thyroidectomy, beta-blockers, corticosteroids). 3) AF data: date and age at diagnosis, temporal relationship to thyrotoxicosis diagnosis, clinical manifestations (palpitation, dizziness, chest pain, dyspnea, or asymptomatic), CHA2DS2-VASc score, treatment (beta-blockers, digoxin, amiodarone, anticoagulants), and complications (stroke, transient ischemic attack, systemic thromboembolism). Patients with structural heart disease (e.g., valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease) or chronic lung disease requiring beta-2 agonists were excluded to minimize confounding causes of AF. AF subtype (paroxysmal vs. persistent/permanent) was recorded when explicitly documented in the medical record; cases without clear subtype documentation were classified simply as AF. 4) Laboratory data: complete blood count (white blood cell (WBC), hemoglobin, hematocrit), renal function (blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine), serum electrolytes, thyroid function tests (TSH, free T3, free T4), and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), as recorded in hospital medical records and performed according to routine clinical practice. 5) Electrocardiography (ECG): 12-lead ECG findings at the time of thyrotoxicosis diagnosis. In accordance with national practice, an ECG was performed in all patients in whom AF was identified, as ECG confirmation is required for AF diagnosis. However, ECG was not routinely performed in all patients with thyrotoxicosis unless clinically indicated, and AF detection therefore depended on clinically driven ECG acquisition rather than universal screening.

Definitions and terms

Thyrotoxicosis was defined as clinical symptoms and signs attributable to thyroid hormone excess, with elevated serum free T4 and/or free T3 levels and abnormal TSH levels. Etiology was determined from medical records, including Graves’ disease, toxic adenoma, multinodular goiter, and drug-induced thyrotoxicosis [17-19].

Thyroid crisis (thyroid storm) was defined as an acute, life-threatening exacerbation of thyrotoxicosis characterized by decompensated organ dysfunction. In this study, thyroid crisis was identified based on physician documentation in the medical records, supported by compatible clinical features such as high fever, tachyarrhythmia, altered mental status, HF, or gastrointestinal/hepatic dysfunction, consistent with established diagnostic criteria (e.g., Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale > 45, or Japanese Thyroid Association definition) [17-19].

AF was defined as atrial fibrillation confirmed by ECG interpretation from cardiologists. In line with national clinical practice in Thailand, which mandates thyroid function testing at the first presentation of AF, this study included only cases in which AF was newly identified during the same clinical encounter as the thyroid evaluation, or when AF prompted the diagnostic workup that led to the identification of thyrotoxicosis. Patients with clearly documented AF occurring before the thyrotoxicosis episode, or with paroxysmal/chronic AF that had been present for years prior to the thyroid assessment, were excluded to ensure that only AF occurring in the clinical context of thyrotoxicosis was included [15, 20].

HF was defined according to the treating physician’s diagnosis as documented in the medical records, based on clinical, echocardiographic, or other relevant investigations available at the time of care. No additional adjudication was performed in this study.

CKD was defined according to physician documentation in the medical records, with estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) calculated using the CKD-EPI equation.

DM, in this study, referred exclusively to type 2 DM (non-insulin-dependent, NIDDM), including patients receiving oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin therapy. Patients with type 1 DM (insulin-dependent, IDDM) were excluded.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) was defined as a documented history of significant CAD requiring revascularization (percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass grafting), as recorded in the medical records. Patients with only chest pain or suspected angina without objective evidence were not classified as CAD.

Old cerebrovascular accident (old CVA) was defined as a history of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke requiring hospitalization, with supportive findings on brain computed tomography (CT) confirming the diagnosis, as documented in the medical records.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Continuous variables were checked for distributional normality and are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) when normally distributed, or as median with interquartile range (IQR) when skewed. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Baseline characteristics were compared between patients with and without AF using the independent t-test or Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data, and Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data.

To identify clinical determinants of AF in thyrotoxic patients, generalized linear models (GLM) with a log link and Poisson distribution with robust standard errors were applied. This method was chosen to provide adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), which are widely used for risk estimation in observational studies and allow for adjustment of multiple covariates. The GLM framework also accommodates predictors that may represent intermediate clinical states, thereby reducing the risk of effect overestimation and improving the validity of associations. Both univariable and multivariable analyses were performed, with results reported as ORs and 95% CIs. A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In addition, we clarified that the GLM with binomial family and logit-link function is mathematically equivalent to traditional logistic regression. It was selected to allow greater modeling flexibility, particularly when incorporating predictors with non-linear patterns or intermediate clinical states, while still producing interpretable adjusted ORs comparable to standard logistic regression.

| Results | ▴Top |

Patient selection and prevalence

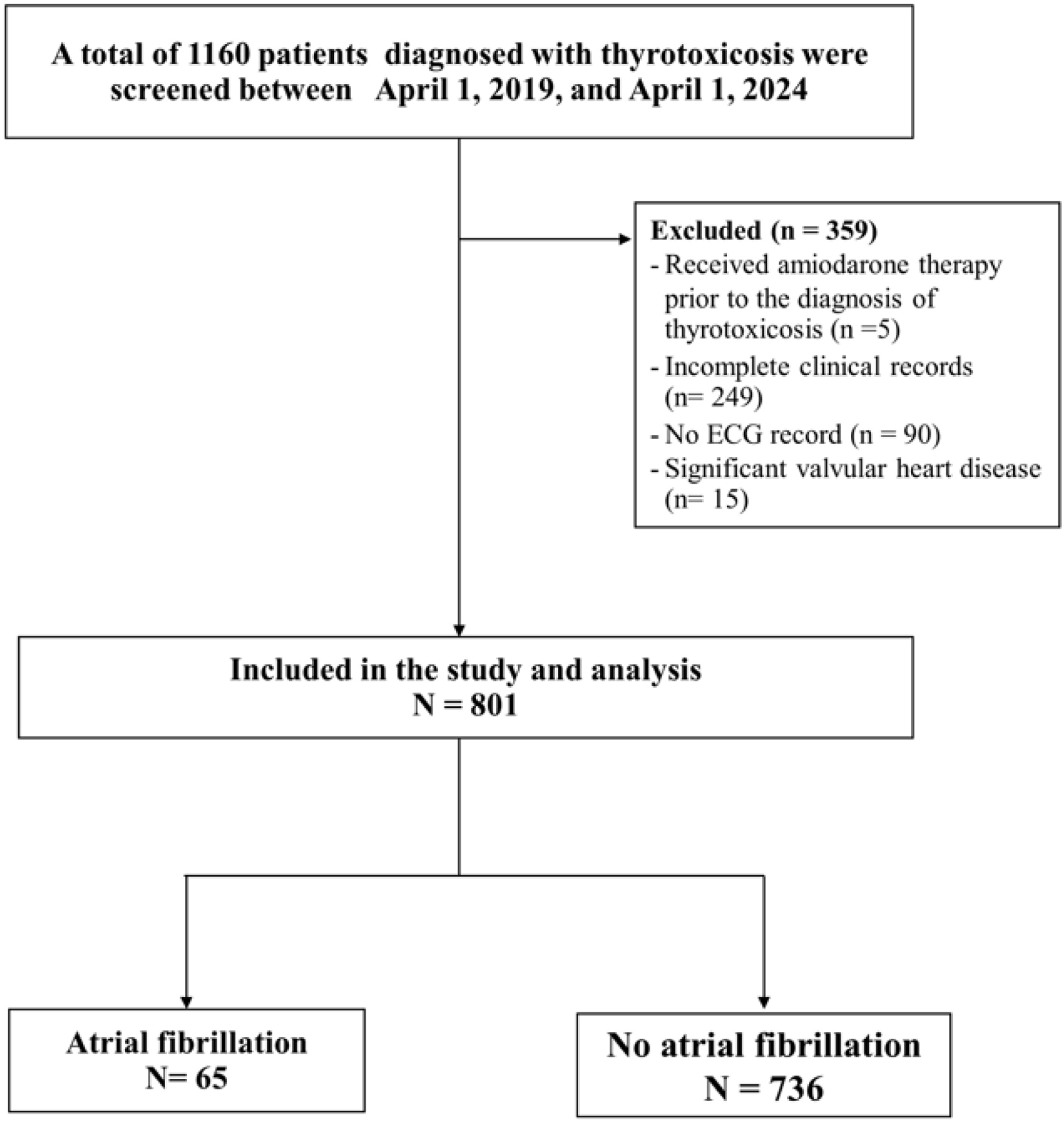

We included 801 patients with thyrotoxicosis and complete records; 65 had concomitant AF and 736 did not, yielding an AF prevalence of 8.11% (95% CI, 6.32 - 10.23). The cohort comprised 21.85% males (n = 175) and 78.15% females (n = 626). The process of patient selection is illustrated in Figure 1.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Flow diagram of patient selection. A total of 1,160 patients with thyrotoxicosis were screened, exceeding the minimum required sample size, and 801 were included in the final analysis. |

Baseline characteristics

AF patients were older (57.11 ± 15.59 vs. 41.75 ± 15.31 years; P < 0.001) and had a higher age at thyrotoxicosis diagnosis (51.68 ± 15.35 vs. 36.33 ± 15.38 years; P < 0.001). BMI, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate did not differ significantly (all P > 0.05), while diastolic blood pressure was higher with AF (76.38 ± 13.34 vs. 72.98 ± 11.42 mm Hg; P = 0.023).

Comorbidities and thyroid-related factors

AF was associated with higher rates of CKD, dyslipidemia, chronic HF, hypertension, and valvular heart disease (all P < 0.001). Thyroid crisis was more frequent in AF (30.77% vs. 1.63%; P < 0.001). Thyrotoxicosis etiologies did not differ between groups (P = 0.573). As summarized in Table 1, AF patients were older, carried more cardiovascular/metabolic comorbidities, and more often had thyroid crisis, while baseline thyroid etiologies were comparable.

Click to view | Table 1. Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Thyrotoxicosis, Stratified by Atrial Fibrillation Status |

Laboratory findings

Renal function

Patients with AF showed impaired renal function compared with those without AF. Mean blood urea nitrogen (BUN) was higher in the AF group (16.25 ± 11.28 vs. 12.32 ± 5.67 mg/dL; P = 0.001), as was serum creatinine (1.11 ± 1.54 vs. 0.72 ± 0.25 mg/dL; P < 0.001), while mean eGFR was lower (84.77 ± 29.30 vs. 101.29 ± 26.49 mL/min/1.73 m2; P < 0.001).

Thyroid function

The AF group had significantly lower mean FT3 levels (11.37 ± 8.48 vs. 14.16 ± 9.76 ng/mL; P = 0.027). No significant differences were observed in FT4 or TSH levels between groups.

Hematology and biochemistry

No significant differences were found in hematocrit, hemoglobin, HbA1c, or serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate) between the two groups.

In summary, laboratory results indicated that patients with AF were more likely to exhibit reduced renal function and lower FT3 levels compared with non-AF patients, while other hematologic and biochemical parameters were comparable. Detailed comparisons are provided in Table 2.

Click to view | Table 2. Laboratory Profiles of Patients With Thyrotoxicosis, Stratified by Atrial Fibrillation Status |

Treatment patterns

Analysis of medication use (Supplementary Material 1, jocmr.elmerjournals.com) revealed clear differences between patients with AF and those without AF.

Cardiovascular and anticoagulant therapy

In the AF group, warfarin (24.62%) and beta-blockers (78.69%) were frequently prescribed, whereas no patients in the non-AF group received these agents. Similarly, AF patients more often received digoxin (20%), amiodarone (11.67%), and other anticoagulants (38.33%). The use of diuretics was also significantly higher in the AF group, including furosemide (12.31% vs. 0.54%; P < 0.001) and spironolactone (7.69% vs. 0.41%; P < 0.001). In addition, aspirin (10.77% vs. 1.09%; P < 0.001) and omeprazole (7.69% vs. 0.95%; P = 0.002) were more commonly prescribed in the AF group.

Antithyroid and adjunctive therapy

Use of methimazole (MMI) was less frequent among AF patients compared with non-AF patients (89.23% vs. 96.60%; P = 0.013). By contrast, propylthiouracil (PTU) use was higher in AF patients (30.77% vs. 11.20%; P < 0.001), potentially reflecting greater disease severity or complications necessitating a switch from MMI to PTU. Corticosteroid use was also more common in the AF group (15.38% vs. 2.05%; P < 0.001).

Other medications

Patients with AF were more likely to receive additional agents for comorbidity management, including antihypertensives (e.g., amlodipine, manidipine) and metabolic drugs (e.g., metformin, simvastatin), consistent with the higher burden of hypertension, chronic HF, and dyslipidemia in this group.

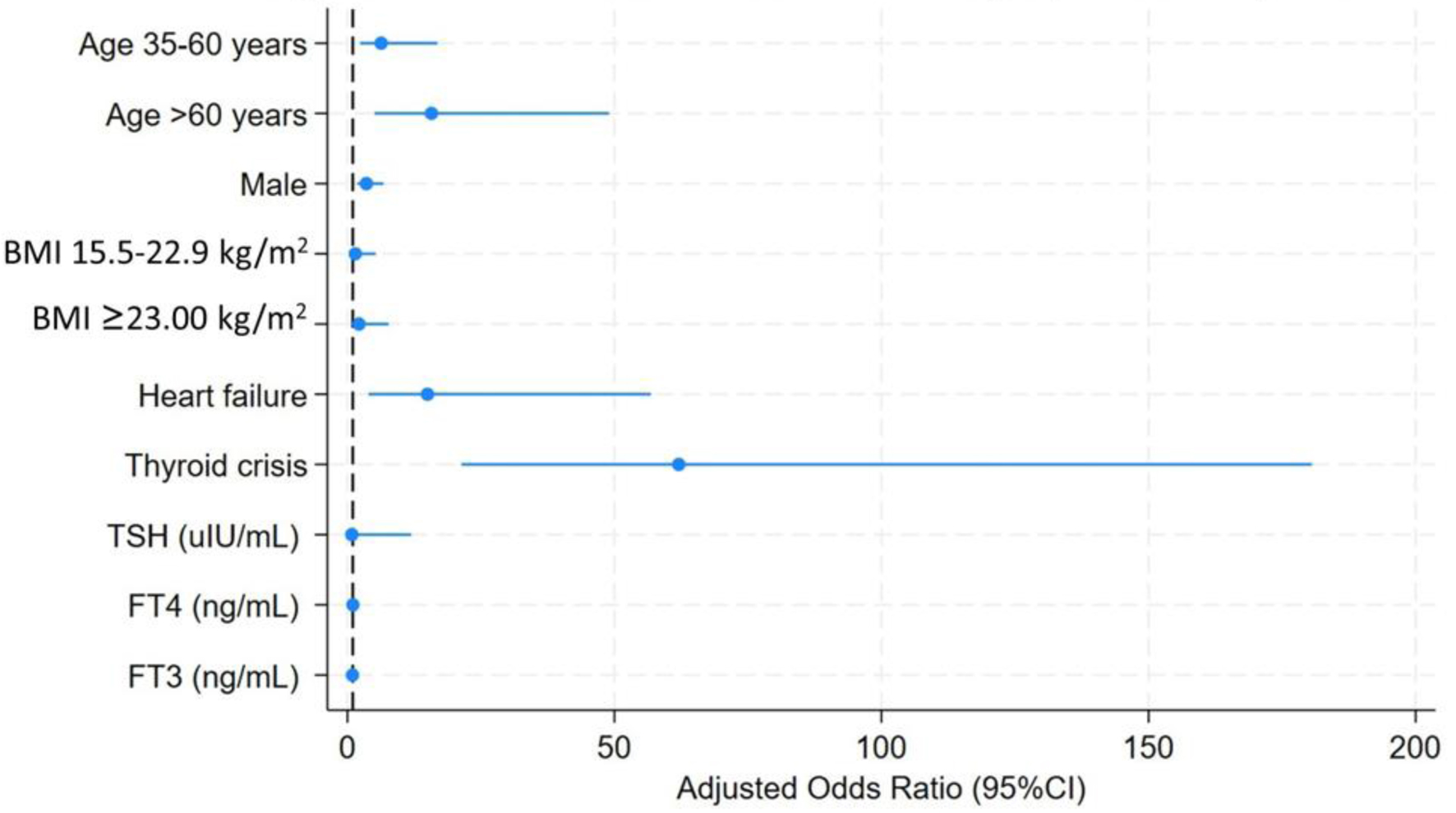

Risk factor analysis

Using GLM with logistic regression (covariates shown in Tables 1 and 2; results summarized in Table 3 and Fig. 2), several factors were independently associated with AF in patients with thyrotoxicosis. Increasing age at diagnosis was a strong predictor: compared with patients younger than 35 years, those aged 35 - 60 years had over a fivefold higher risk of AF (adjusted OR = 5.48; 95% CI: 2.03 - 14.83; P = 0.001), while patients older than 60 years showed an elevenfold greater risk (adjusted OR = 11.39; 95% CI: 3.43 - 37.76; P < 0.001). Male sex was also a significant determinant, conferring a more than threefold increased risk compared with females (adjusted OR = 3.38; 95% CI: 1.70 - 6.30; P < 0.001).

Click to view | Table 3. Prognostic Factors Associated With AF Among Thyrotoxicosis Patients |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Forest plot of prognostic factors associated with atrial fibrillation among patients with thyrotoxicosis. Adjusted odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals were estimated using generalized linear models with logistic regression. Increasing age, male sex, heart failure, and thyroid crisis were independently associated with atrial fibrillation, whereas thyroid hormone levels were not significant predictors. |

BMI categories did not demonstrate significant associations, although a trend toward higher AF risk was observed in patients with BMI ≥ 23 kg/m2 (adjusted OR = 2.11; 95% CI: 0.59 -7.60; P = 0.253). Traditional cardiovascular comorbidities such as DM and hypertension lost statistical significance after adjustment (all P > 0.05). In contrast, chronic HF remained a powerful independent risk factor, with more than 11-fold higher odds of AF (adjusted OR = 11.25; 95% CI: 2.85 - 44.54; P = 0.001). The strongest predictor identified was thyroid crisis, which increased the risk of AF over 60-fold (adjusted OR = 61.84; 95% CI: 21.89 - 181.32; P < 0.001).

By comparison, thyroid function parameters (TSH, FT4, FT3) were not significantly associated with AF in the adjusted models (all P > 0.05). These findings highlight that clinical characteristics, especially age, sex, HF, and thyroid crisis, are more informative determinants of AF risk in thyrotoxicosis than hormone levels alone.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Prevalence of AF in thyrotoxicosis

In this cohort, AF was observed in approximately 8% of patients, consistent with prior reports (5-15%) [1, 12-14]. Variability across studies likely reflects differences in case ascertainment, disease severity, and study design. Hospital-based cohorts, such as ours, may overrepresent patients with severe disease or crisis, whereas population-based studies may underestimate prevalence if paroxysmal AF is missed. This reinforces that AF is a clinically relevant but not universal manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.

From a global epidemiological perspective, the incidence of AF in hyperthyroidism has been reported to be two to three times higher than in the general population, particularly among older men [2, 3, 13]. The prevalence of about 8% observed in our Southeast Asian cohort is therefore consistent with the literature and highlights that this burden is a cross-regional phenomenon rather than one confined to Western populations.

Host vulnerabilities: age, sex, and cardiovascular comorbidity

Our data confirmed that advancing age, male sex, and HF were the strongest host-related determinants of AF in thyrotoxicosis. Compared with patients diagnosed before age 35, the risk was more than fivefold higher at ages 35 - 60 and over 11-fold higher beyond 60 years, underscoring the contribution of age-related atrial remodeling and fibrosis.

Although men were less frequently diagnosed with hyperthyroidism, they exhibited more than a threefold higher likelihood of AF. This pattern parallels the male predominance in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and suggests that men may be physiologically more vulnerable to the arrhythmogenic effects of thyroid hormone excess.

HF further amplified the risk of AF, with more than an 11-fold increase. This relationship is bidirectional: thyrotoxic AF can precipitate decompensated HF; while pre-existing HF provides a susceptible atrial substrate that facilitates AF once exposed to thyroid hormone excess.

At the cellular level, thyroid hormone excess increases atrial automaticity and shortens the refractory period through β-adrenergic receptor upregulation and ion channel remodeling [3, 21]. However, the persistence of AF requires structural substrates such as atrial fibrosis, diastolic dysfunction, or remodeling, which are more prevalent in elderly patients and in men [4, 6]. This mechanistic interplay explains why sex and age exert stronger influences on AF risk than hormone levels alone.

Thyroid crisis versus hormone levels

Among thyroid-specific factors, thyroid crisis emerged as the most powerful determinant, increasing AF risk more than 60-fold. Crisis represents not only hormone excess but also a maladaptive systemic response, including sympathetic overactivation, electrolyte imbalance, hypoxemia, and multi-organ decompensation, that acts as a potent clinical accelerator [17-19]. Patients experiencing thyroid storm therefore face a markedly heightened arrhythmogenic burden, even when their absolute FT3 or FT4 levels are not substantially different from those of non-crisis patients. This observation aligns with our finding of an adjusted OR of about 62.

By contrast, absolute hormone concentrations (TSH, FT4, FT3) were not significant predictors after adjustment. This is consistent with prior studies showing heterogeneous results: while excess thyroid hormone may contribute to atrial excitability, the interplay of host vulnerability and systemic crisis response is more decisive [3, 6, 16]. Taken together, these results suggest that AF risk in thyrotoxicosis is defined less by “how high the hormones are” and more by “how the body responds” [1, 22].

It is also important to recognize that FT3 levels may paradoxically fall in severe thyrotoxicosis or systemic illness, a phenomenon consistent with the “low T3 syndrome.” In thyroid crisis, increased metabolic demand, impaired peripheral conversion of T4 to T3, cytokine-mediated inhibition of deiodinase activity, and accelerated tissue consumption of T3 may all contribute to reduced circulating FT3 levels despite marked clinical severity. These mechanisms help explain why absolute FT3 concentrations did not correlate with AF risk in our cohort.

Beyond systemic crisis effects, thyroid hormone exerts direct electrophysiologic influences through receptor-mediated pathways. Triiodothyronine acts primarily on TRα1 receptors, the dominant cardiac isoform, leading to increased β-adrenergic receptor density, enhanced L-type calcium channel activity, and upregulation of Na+/K+-ATPase. These changes shorten atrial action potential duration and refractory periods through potassium channel remodeling, thereby promoting atrial automaticity and reentry susceptibility. Although these mechanisms facilitate arrhythmogenesis, they require pre-existing structural substrates, such as fibrosis, diastolic dysfunction, or atrial dilation, to sustain AF, which explains why hormone levels alone did not predict AF risk in our study.

Reversibility and long-term implications

Although restoration of euthyroidism can promote rhythm recovery in some patients, prior studies have reported that only 40-60% of thyrotoxic AF cases revert to sinus rhythm after achieving euthyroidism [7-9]. Our findings suggest that patients with high-risk profiles, such as those older than 60 years, men, individuals with HF, or those experiencing thyroid crisis, are less likely to recover sinus rhythm. In these groups, persistent atrial remodeling and structural substrates may outweigh the reversible effects of thyroid hormone excess.

This highlights the need for systematic AF surveillance in all thyrotoxic patients, including routine ECG assessments during follow-up, even after normalization of hormone levels. Reliance on thyroid function tests alone may underestimate residual arrhythmic burden. Importantly, when AF is detected, it should be managed according to established AF guidelines rather than assumed to resolve spontaneously with thyroid control.

Conceptual integration and clinical implications

Taken together, our findings support a “three-hit hypothesis” model of AF in thyrotoxicosis. In this framework, thyroid hormone excess serves as the trigger, host vulnerabilities such as advancing age, male sex, and HF provide the substrate, and thyroid crisis functions as the accelerator. This synergistic interaction explains why AF develops in only a subset of patients and why thyroid crisis confers disproportionate risk [23].

In addition to the dominant effects of age, male sex, and HF, our data demonstrate that chronic comorbidities such as CKD contribute substantially to the arrhythmogenic substrate in thyrotoxicosis. Notably, these clinical vulnerabilities showed much stronger associations with AF than the absolute levels of FT3 or FT4. This pattern reinforces the concept that structural and systemic susceptibility plays a more decisive role than biochemical severity alone in the development of AF.

The clinical implications are clear. Clinicians should not overlook AF in thyroid clinics, particularly in men, older adults, and those with HF. Routine ECG assessment should be integrated into follow-up care, as reliance on symptoms or hormone normalization alone risks under-recognition. Furthermore, applying this conceptual model may help stratify patients into those with a higher likelihood of rhythm reversibility versus those who require long-term AF management.

The external validity of our findings is supported by the similarity of AF prevalence in our Southeast Asian cohort to that reported in Western populations (5-15%). Although Asian patients exhibit distinctive thyrotoxicosis phenotypes, including higher rates of Graves’ disease and thyrotoxic periodic paralysis, as well as heightened β-adrenergic sensitivity, the overall arrhythmogenic burden appears comparable [24]. These observations suggest that the mechanistic model identified in this study is broadly generalizable across populations, while still acknowledging regional differences in disease expression.

Future research should include external validation in prospective cohorts with standardized crisis scoring, serial hormone profiling, and AF classification. Investigation into biomarkers of susceptibility and reversibility, such as atrial fibrosis markers, autonomic activity indices, and inflammatory mediators, may further refine risk stratification and guide personalized management strategies.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective single-center design may limit generalizability, although the large sample size from a tertiary hospital still reflects real-world practice. To strengthen external validity, future prospective multi-center studies are warranted to confirm these findings. Second, AF diagnosis was based on routine ECGs, so paroxysmal or subclinical AF may have been missed without continuous monitoring. Third, thyroid hormone assays were derived from routine testing, which may introduce inter-assay variability. Fourth, despite multivariable adjustment, residual confounding cannot be excluded. Fifth, treatment choices, including antithyroid regimens and anticoagulation, were not randomized and may reflect physician preference or disease severity. Sixth, because long-term follow-up data were not uniformly available, the study could not assess AF recurrence or the influence of long-term thyroid hormone therapy (e.g., antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine, or surgery) on sustained rhythm outcomes. This limits our ability to determine whether treatment modality affects AF persistence or reversibility.

In addition, AF identification relied on clinically driven ECG acquisition rather than universal ECG screening, and AF subtype could be classified only when explicitly documented in the medical record. As with all retrospective studies, these constraints may have led to partial under-recognition of paroxysmal AF.

These limitations, however, do not diminish the central finding that host vulnerabilities and thyroid crisis, rather than hormone levels alone, were the primary determinants of AF in thyrotoxicosis.

Conclusion

In this cohort of patients with thyrotoxicosis, AF was observed in approximately 8%, with risk strongly shaped by host factors rather than hormone levels alone. Older age, male sex, and HF provided the vulnerable substrate, while thyroid crisis acted as the most powerful clinical accelerator. By contrast, absolute thyroid hormone concentrations were not independently associated with AF after adjustment.

These findings underscore that arrhythmic risk in thyrotoxicosis reflects the interplay between thyroid-specific triggers and host-specific vulnerabilities. Clinicians should actively assess for AF in thyrotoxic patients, particularly men, the elderly, and those with HF, rather than assuming arrhythmia will resolve with normalization of thyroid function. Future studies with prospective designs and biomarker evaluation are needed to refine risk stratification and guide long-term management strategies.

| Supplementary Material | ▴Top |

Suppl 1. Medications for the management of patients.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank all participants for their contributions to this study. We are especially grateful to Prof. Dr. Jayanton Patumanond for expert guidance on statistical analysis. The authors also appreciate the collaborative input from colleagues throughout the research process.

Financial Disclosure

This research was supported by the Faculty of Medicine, Burapha University, Chonburi, Thailand.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

CK and SK conceptualized the study and collected clinical data. AP, VR, and KK performed statistical analysis and drafted the initial manuscript in collaboration with CK. All authors contributed to interpretation of results, provided critical revisions, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Any inquiries regarding supporting data availability of this study should be directed to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

AF: atrial fibrillation; BMI: body mass index; CAD: coronary artery disease; CI: confidence interval; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CVA: cerebrovascular accident; DM: diabetes mellitus; ECG: electrocardiography; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; FT3: free triiodothyronine; FT4: free thyroxine; HbA1c: hemoglobin A1c; HF: heart failure; ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; IRB: Institutional Review Board; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation; TSH: thyroid-stimulating hormone

| References | ▴Top |

- Kostopoulos G, Effraimidis G. Epidemiology, prognosis, and challenges in the management of hyperthyroidism-related atrial fibrillation. Eur Thyroid J. 2024;13(2).

doi pubmed - Frost L, Vestergaard P, Mosekilde L. Hyperthyroidism and risk of atrial fibrillation or flutter: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(15):1675-1678.

doi pubmed - Bielecka-Dabrowa A, Mikhailidis DP, Rysz J, Banach M. The mechanisms of atrial fibrillation in hyperthyroidism. Thyroid Res. 2009;2(1):4.

doi pubmed - Biondi B, Kahaly GJ. Cardiovascular involvement in patients with different causes of hyperthyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6(8):431-443.

doi pubmed - Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2016;41(2):65-92.

doi pubmed - Biondi B, Cooper DS. The clinical significance of subclinical thyroid dysfunction. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(1):76-131.

doi pubmed - Nakazawa HK, Sakurai K, Hamada N, Momotani N, Ito K. Management of atrial fibrillation in the post-thyrotoxic state. Am J Med. 1982;72(6):903-906.

doi pubmed - Akbulut B, Dogan O, Guvener M, Yilmaz M. Cardiovascular medicine. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:217-25.

- Babenko AY, Bairamov AA, Grineva EN, Ulupova EO. Thyrotoxic cardiomyopathy: INTECH Open Access Publisher; 2012.

- Khomsanoi N, Chombandit T, Wiwatmanaskul J, Kreepala C. Economic evaluation of inpatient medication reconciliation with a subtraction strategy. Health Econ Rev. 2025;15(1):52.

doi pubmed - Kreepala C, Famulski KS, Halloran PF. Fundamental concepts regarding graft injury and regeneration: tissue injury, tissue quality, and recipient factors. Textbook of organ transplantation. 2014:99-118.

- Naser JA, Pislaru S, Stan MN, Lin G. Incidence, risk factors, natural history and outcomes of heart failure in patients with Graves' disease. Heart. 2022;108(11):868-874.

doi pubmed - Reddy V, Taha W, Kundumadam S, Khan M. Atrial fibrillation and hyperthyroidism: A literature review. Indian Heart J. 2017;69(4):545-550.

doi pubmed - Selmer C, Olesen JB, Hansen ML, Lindhardsen J, Olsen AM, Madsen JC, Faber J, et al. The spectrum of thyroid disease and risk of new onset atrial fibrillation: a large population cohort study. BMJ. 2012;345:e7895.

doi pubmed - Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, et al. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373-498.

doi pubmed - Sawin CT. Subclinical hyperthyroidism and atrial fibrillation. Thyroid. 2002;12(6):501-503.

doi pubmed - Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Greenlee MC, Laurberg P, Maia AL, Rivkees SA, et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of Hyperthyroidism and Other Causes of Thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid. 2016;26(10):1343-1421.

doi pubmed - Bahn Chair RS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, Garber JR, Greenlee MC, Klein I, Laurberg P, et al. Hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association and American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Thyroid. 2011;21(6):593-646.

doi pubmed - Feingold K, Anawalt B, Boyce A, Chrousos G, de Herder W, Dhatariya K, et al. Thyrotoxicosis of other etiologies. Endotext. 2000.

- January CT, Wann LS, Calkins H, Chen LY, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland JC, Jr., Ellinor PT, et al. 2019 AHA/ACC/HRS Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(1):104-132.

doi pubmed - Klein I, Danzi S. Thyroid disease and the heart. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1725-1735.

doi pubmed - Chaker L, Heeringa J, Dehghan A, Medici M, Visser WE, Baumgartner C, Hofman A, et al. Normal thyroid function and the risk of atrial fibrillation: the rotterdam study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(10):3718-3724.

doi pubmed - He CJ, Zhu CY, Fan HY, Qian YZ, Zhai CL, Hu HL. Low T3 syndrome predicts more adverse events in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin Cardiol. 2023;46(12):1569-1577.

doi pubmed - Takawale A, Aguilar M, Bouchrit Y, Hiram R. Mechanisms and management of thyroid disease and atrial fibrillation: impact of atrial electrical remodeling and cardiac fibrosis. Cells. 2022;11(24):4047.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Clinical Medicine Research is published by Elmer Press Inc.